Coronavirus: What I learnt in Oxford’s vaccine trial

This feature is currently in beta testing and uses a computer-generated synthetic voice. There may be some errors, for example in pronunciation, sentiment and tone.

The Covid-19 vaccine developed by Oxford University has shown tantalising results so far. Richard Fisher describes what it’s like to be one of the volunteers in the clinical trials.

I

I’m sitting in a hospital reception, and my breath is fogging my glasses. Minutes ago, I had been running through humid streets, late for my appointment. As doctors and nurses stroll past on their way to work, I’m aware that I don’t look particularly well.

The last time I was at St George’s Hospital in Tooting, south London, it was for the birth of my daughter. It feels very different today. I can smell the bleach used to clean the floors through my face mask, and the adjacent seat is taped off, warning nobody to sit down next to me.

Two hospital staff-members in scrubs and masks approach, one of them holding a sign that reads “vaccine trial” like a taxi driver waiting at an airport arrivals gate.

The sign is for me. I follow them in a slow procession, two metres behind, as the pair share gossip from the wards.

I’m at St George’s for an initial screening as a volunteer in the Oxford University trial to test the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. In the coming weeks, I will learn what it is like to be a participant in one of the world’s most promising efforts to tackle to the coronavirus pandemic. Of all the vaccine trials ongoing around the world, the Oxford effort is ahead of most of the pack.

You might also like:

- The undetected immunity against Covid-19

- How the malaria vaccine could change global health

- Can you catch Covid-19 twice?

A few weeks later, on 20 July, the researchers would announce extremely promising initial results, based on the first 1,077 people, suggesting that the vaccine is both safe and triggers an immune response. “There is still much work to be done…but these early results hold promise,” Sarah Gilbert of the University of Oxford said in a statement. The next step involves expanding the trial at a higher dose to thousands more people, volunteering at sites across the UK, as well as Brazil and South Africa. This phase of the clinical trials, to test efficacy on a much bigger scale, is what I have signed up for.

Screening

My journey here started one late night in late May, when I stumbled on a tweet from an Oxford University philosopher about a vaccine study that I was aware had been moving fast. He’d volunteered. So, as my wife slept next to me, I also filled out the form on the group’s website, and forgot about it.

A few weeks later, I am in a neurology ward repurposed for the Oxford trial, watching one of the lead scientists, Matthew Snape, on a large projector screen explaining what to expect as a volunteer in their trial – what we can and can’t do, how the science behind the vaccine works, and what side-effects to watch out for.

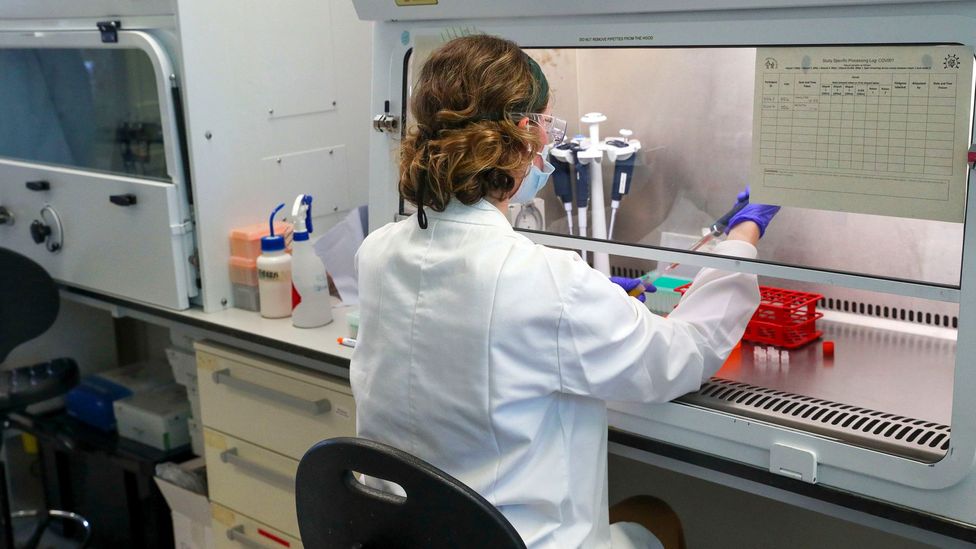

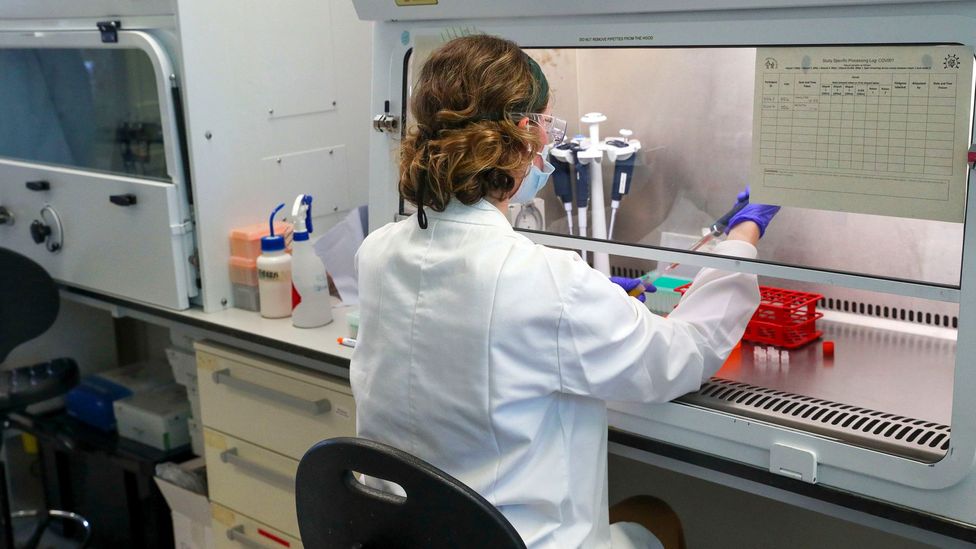

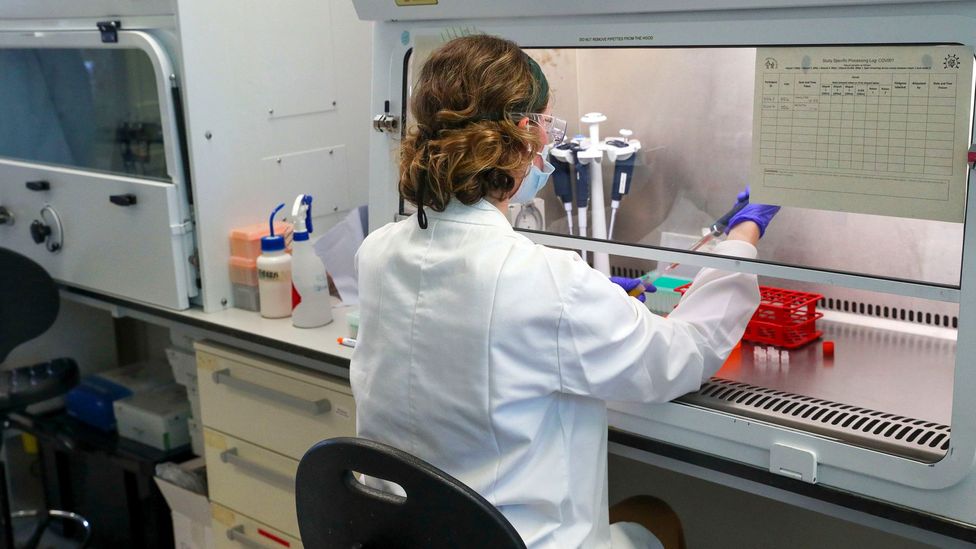

A scientist at the Oxford Vaccine Group’s facility at the Churchill Hospital in Oxford (Credit: Steve Parsons/PA Wire)

There will be 10,000 of us, Snape explains, and we will be randomly sorted into two groups. One group will receive a vaccine that won’t offer any protection against the coronavirus and the other half will get the test vaccine – ChAdOx1 nCoV-19.

This vaccine is built upon a weakened version of a common cold virus that typically infects chimpanzees. It’s a technique that the group had already been developing before the pandemic, to tackle Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) and Ebola. And it’s why they were able to move so fast in response to Covid-19. In the early months of 2020, when the world was stumbling towards the grim realisation that this pandemic wasn’t going away, the Oxford group was scrambling to refocus their work on the crisis.

Snape explains what they did on the video I’m watching. First, they took the chimp cold virus and genetically altered it so it is impossible to grow in humans (phew). Next they added genes that make proteins from the Covid-19 virus, called spike glycoprotein. If the body learns to recognise and develop an immune response to this spike glycoprotein, the hope is that it will help stop the Covid-19 virus from entering human cells.

Half the volunteers will get this vaccine, Snape explains. The second group will be given an existing licensed vaccine called MenACWY (either Nimenrix or Menveo), which is used to protect against the causes of meningitis or sepsis. This vaccine is a “control” for comparison, and was chosen instead of an inert placebo so that the control group experience the effects (and side-effects) of a real vaccine, preventing them from working out which group they are in. Since 2015, MenACWY has been given routinely to teenagers in the UK, and also as a travel vaccine to high-risk parts of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa. Saudi Arabia requires proof of MenACWY vaccination for participants in the annual Hajj.

After the video, I am quizzed in-depth about my medical history, and whether I have had any symptoms of the coronavirus. A sample of my blood is taken for analysis, and I have to agree consent for various study procedures: I agree to allow photos of the injection site; I will not donate blood; if I am a woman of child-bearing potential I agree to use effective contraception, and so on. One caught my attention: “I agree that the samples collected will be considered a gift to Oxford University.” I couldn’t help but smile knowing that some participants, in a different cohort of the same trial, would be asked to submit faecal samples.

I return home, feeling more informed, but also slightly more apprehensive than before. Like any clinical trial, it’s necessary to ensure participants are fully aware of potential side-effects, from the mild (nausea, headaches and so on) to the rare and severe (Guillain-Barre syndrome, which causes severe weakness and can be fatal). While I know that the risks are small, I can’t deny it’s somewhat daunting to hear them all in one go.

At the screening, volunteers even had to be briefed on “theoretical concerns” that the vaccine could make the effects of coronavirus worse. Some studies on animals that received experimental vaccines to protect against Sars (a related virus) have shown worsened lung inflammation when they were infected with Sars. One report had found similar lung inflammation in vaccinated mice infected with Mers. The effect had thankfully not been seen in animal studies for the Oxford Covid-19 vaccine, however.

Most of all, I felt reassured to hear that thousands of people had already received the Oxford vaccine without severe side-effects – which was confirmed by the group’s study in the Lancet journal on 20 July. (And just to be absolutely clear, none of these potential reactions should bolster the unfounded claims of anti-vax campaigners).

Vaccine day

A week later, I am back in the windowless room at St George’s where I had my screening appointment. It’s supposed to be vaccination day, but now I’m worried I’m about to be kicked out of the trial.

The doctor, Eva Galiza, has left the room, and she hasn’t returned for more than 10 minutes. Moments earlier, she had explained that it’s the last day of the Oxford trial at St George’s Hospital, and they were close to running out of samples.

The next stage of the Oxford trial includes volunteers in Brazil, where the coronavirus is currently more prevalent (Credit: Getty Images)

We go through my medical history again, take more blood, but Galiza – a paediatric vaccine researcher recruited to the trial team – has no idea if I can participate until she arrives at the pharmacy. I am intrigued to learn at this point that she is as in the dark as me about what will happen next. To ensure the trial results are fully robust, both the participants and the doctors injecting the vaccine do not know whether it is the experimental one or the control vaccine for meningitis/sepsis in the syringe.

While she is gone, I am left alone with my thoughts. They inevitably stray to the world outside. In England, where I live, it’s the day before many of the lockdown rules are eased and many businesses can finally open again, from pubs to hairdressers. The social distancing guidance for England is also changing from two metres to one metre plus. These looming changes have prompted both excitement and nervous trepidation.

My mind wanders to think of friends and family in other parts of the world, each experiencing the pandemic at different stages – some celebrating a virus-free country, others on an upwards curve towards a grim death-toll. For much of the previous year, I had lived in Massachusetts. On the day of my appointment, the news reports were grim for the people I knew back in the US – the country had experienced more than 40,000 daily cases on four separate days within a week, and the country was on a chilling trajectory.

I’d also heard the latest numbers from Brazil on my drive over – a friend and his wife had recently returned there – that day, the country was nearing 1.5 million infections. Brazil’s widespread outbreak is part of the reason the Oxford vaccine trial is now expanding to test volunteers in Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo and a site in northern Brazil. They’re doing the same in South Africa.

The sad truth is that a volunteer like me in the UK is less likely to tell the scientists if their vaccine shows efficacy, because for now at least, I am less likely to catch the virus than somebody where the pandemic is spreading through the community. For the greater good, some of the 10,000 volunteers in my stage of the trial will need to encounter this killer.

When Galiza returns she is holding a vial. I can’t see her face behind her mask, but her eyes are smiling. After weeks of waiting, a sharp scratch on my arm and a few seconds of injection, there’s a vaccine entering my bloodstream. And it’s 50:50 about which one it is. I won’t know until the trial is over.

Swabs and waiting

The next stage is the long haul. The participants have been divided into groups, each with a different schedule of symptom reporting, testing and blood samples. For me, the next step comes seven days after the vaccine, and I’ve not especially been looking forward to it.

I have to rub my tonsils with a cotton bud swab for 10 seconds, without touching my teeth or tongue (not easy, it’s like the board game Operation), then stick the same stick up my nose as far as it will go. I’d read that if the nasal swab is done properly, it’ll feel like “tickling your brain”. It’s not quite that bad, but it’s not comfortable.

Some of the first South African vaccine trial volunteers, where the Oxford effort is also testing for efficacy (Credit: EPA)

I then place the swab into a sealed bag and security-sealed box that says “Biological Substance Category B”, and post it into a special Priority Postbox that the Royal Mail has introduced all over the UK, ready for home tests. A few days later, I get a text on my phone telling me my coronavirus test result is negative.

When taking the swabs, I also fill out a questionnaire that quizzes me about my behaviour in the previous week. “Have I been on public transport?” “How many people outside my household did I spend more than five hours with?”

I will repeat this routine once a week for at least four months, as well as returning to the hospital regularly for blood tests over the next year.

It’s this necessary but long-term process that some people – many of them politicians – fail to understand about the coronavirus vaccine trials. You can’t throw money at the problem and hope results happen faster. While the Oxford vaccine trial has already shown promising safety results, and the tantalising possibility of a protective immune response, it was only in 1,000 people. To roll out a vaccine to millions (or the whole world), you need a level of confidence that can only come with patience and more data.

Public health officials will remember well the times that vaccine rollouts went wrong. In 1976, fears of a swine flu outbreak led the US government to accelerate vaccine development and inoculate tens of millions of Americans. The feared pandemic never arrived, but by some estimates, around 30 people died due to adverse vaccine reactions. Such mistakes may well have dented trust in public health advice and fuelled anti-vax fears too, which is the last thing you need in a pandemic.

The looming decisions for the medicine approval bodies around the world will come with heavy responsibilities. As Sir John Bell, professor of medicine at Oxford University, told the BBC Today programme on 21 July, we don’t have the luxury of waiting for the definitive evidence that we’d normally have from a clinical trial. “The toughest job of anybody is the regulator, who has to make the call on whether it is safe and effective to roll out to the public. I would not want that job,” he said. “It’s a really hard call. If they say yes, there will suddenly be a queue of three-and-a-half billion people asking for a vaccine.”

Once a week, I swab my tonsils and nose before posting the sample in a Royal Mail “priority postbox” (Credit: Richard Fisher)

Another reality is that the initially approved vaccines may also not be the “sterilising” panacea that many imagine, totally preventing the disease. In other words, they may not completely clear the virus, but instead mitigate its effects. People could still carry the virus even if they don’t suffer symptoms, for example, spreading it to the unvaccinated. That protection would still be of huge value, but whatever happens, we need to be prepared for the long-haul. This virus might always be with us.

As for me, knowing there’s a 50:50 chance I received a dose of a promising vaccine provides a small comfort, but it certainly won’t change my behaviour or my choices. Nor should it – the researchers were clear about that. Until I know for sure that we have a vaccine that works – protecting my wife, daughter, friends, family and strangers I pass on the street – I will continue to follow social distancing guidance.

Mainly, I’m pleased to have the opportunity to play a very small part – along with 10,000 other people – in a trial that the whole world is watching. The pace at which the Oxford group has responded to this crisis, and the hard work and organisation of the people involved, is seriously impressive. Before the pandemic, many of these doctors and researchers were working in relatively obscure corners of vaccine development or paediatrics, pursuing their work through scientific curiosity or an individual sense of purpose. They never expected to carry the hopes and expectations of billions of people on their shoulders.

The Oxford vaccine trial may not turn out to be the success that many wish for. It may not meet the safety and efficacy threshold that takes us out of these difficult times. But that’s how science works – it’s long-term, collective and filled with wrong turns – and right now I’ve never been more glad that we have it.

—

As an award-winning science site, BBC Future is committed to bringing you evidence-based analysis and myth-busting stories around the new coronavirus. You can read more of our Covid-19 coverage here.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.