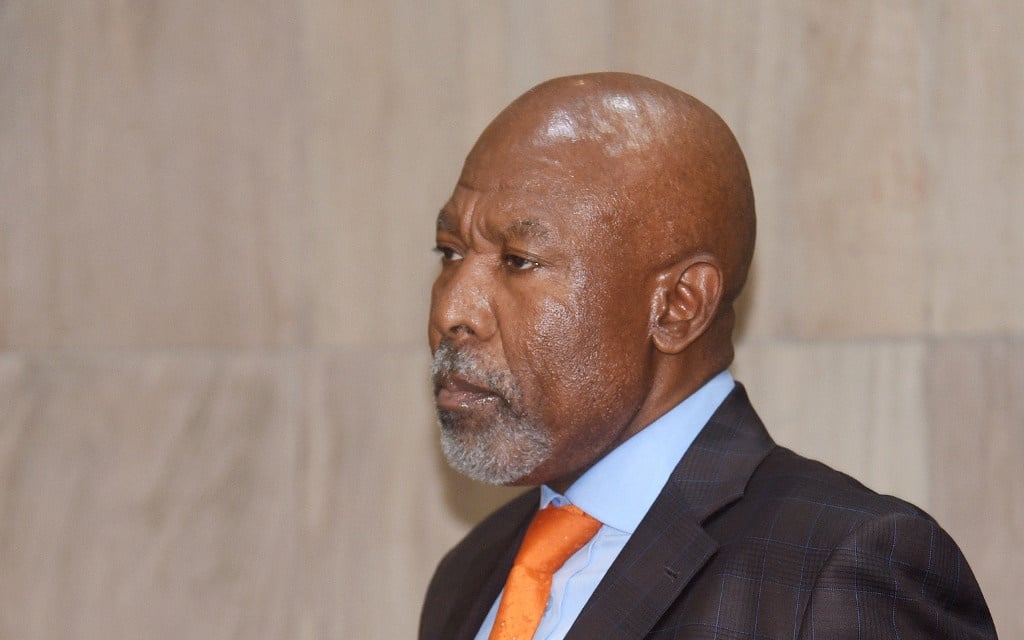

South African Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago announces a repo rate cut at central bank’s head office on January 16, 2020 in Pretoria.

Gallo Images/Business Day/Freddy Mavunda

- Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago has warned that embarking on a large scale quantitative easing programme would be risky.

- The central bank has been criticised for being conservative in its approach to responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, with calls for it to take on government debt directly.

- The governor says these options might send out a “dangerous signal” to markets.

Rolling out a full-blown quantitative easing programme could risk bankrupting the SA Reserve Bank, leaving it dependent on National Treasury for a bailout, the central bank’s Governor Lesetja Kganyago warned on Thursday.

Kganyago gave a virtual lecture hosted by Wits University on the role of the central bank in responding to the impact of Covid-19.

Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic the bank has deployed several monetary policy tools to assist indebted consumers and businesses, such as lowering the repo rate by a total 275 basis points, relaxing rules to allow commercial banks to lend more, and purchasing over R20 billion worth of government bonds on the secondary market to counteract “dysfunction”.

But critics have argued the bank has been too conservative in its approach. There have been calls from some quarters of the ANC for quantitative easing or QE – a process of introducing new money into the system by, for example, purchasing bonds.

“Sometimes I think that if we just told people our asset purchases were QE, they might stop complaining that ‘the SARB is conservative’ – a criticism that has somehow survived despite surprise at how much the SARB has already done,” Kganyago said.

He added that the conditions the South African economy is facing do not necessarily warrant “full-blown” QE.

- READ | SA failed to rebuild buffers post-2008, says Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago

Kganyago pointed out that liquidity problems in financial markets were not the only challenges created by Covid-19: the pandemic is also putting strain on the fiscus with the risk of increasing debt to unsustainable levels. Deputy Finance Minister David Masondo has previously said he is not opposed to the Reserve Bank buying government bonds directly from Treasury, essentially taking on government debt.

There have also been calls for the bank to help finance R1 trillion in stimulus spending, or to buy between R10 billion to R20 billion worth of bonds per week to finance economic recovery, Kganyago said.

“These numbers imply that the SARB would be buying, more or less, all new debt for the foreseeable future. Such interventions would crowd pension funds and other institutional investors out of the bond market,” he said.

- WATCH | FIN24 SPEAKS | SARB governor Lesetja Kganyago on monetary policy in a post-Covid-19 world

Dangerous signal

This would send out a “dangerous signal” about its monetary policy, namely that it would be fully financing the public sector instead of protecting the value of the currency, as mandated by the Constitution. Bondholders might then dump their bonds on the bank to minimise their losses, he explained.

“The SARB cannot take responsibility for solving a fiscal sustainability problem, nor can it jeopardise the value of the currency by agreeing to inflationary money printing,” said Kganyago.

The governor has been stern in his view on keeping the bank independent, avoiding interfering in fiscal policy.

- READ | SA Reserve Bank rules out financing government budget deficit

A large QE programme carries the risk of being inflationary, and costly to the Reserve Bank, so much so it could render the bank insolvent within a year, Kganyago said. This would add to Treasury’s debt burdens. “A big QE operation wouldn’t lift the budget constraint. Instead, it would end up saddling the Treasury with yet another bankrupt government enterprise asking for a bailout,” Kganyago said.

“Once a central bank approaches a Treasury for a bailout, that is the end of the independence of the central bank,” he stressed.

Kganyago raised concerns about the country’s contracting growth rates, and rising debt levels. “We have just completed our worst growth decade on record – worse than the 1980s or the 1990s,” he said. The bank projects the economy to contract by as much as 7% this year, the worst seen since the Great Depression.

“We risk following Argentina’s path, where ideological conflicts and unstable macroeconomic policies produced a steady economic decline… we now find ourselves sitting on the highest debt pile in our history, arguing about printing money and waving ideological banners at each other,” he added.

Kganyago said it was important to make the most of having low inflation currently to forge a path for economic recovery. “We can set out now on a new path with low interest rates if we guard and value them. We have nearly all the ingredients needed to get permanently stronger economic growth, create jobs, and rid ourselves of poverty and inequality,” he said.