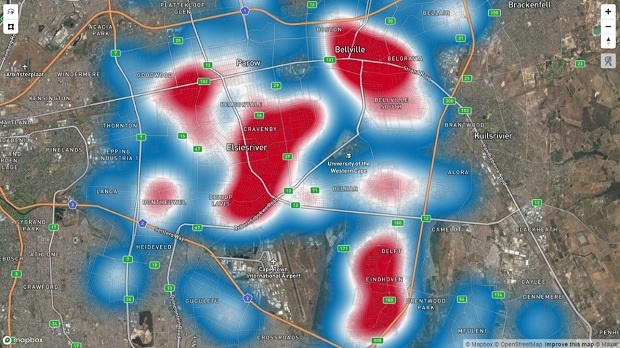

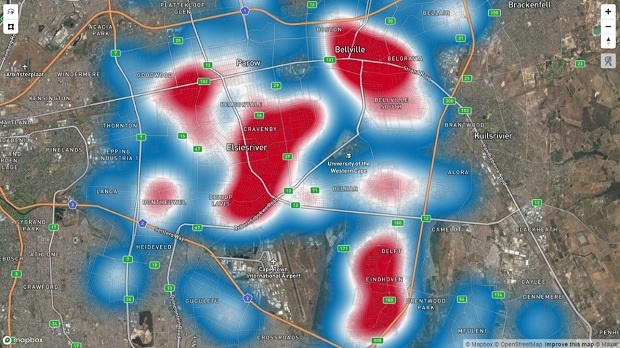

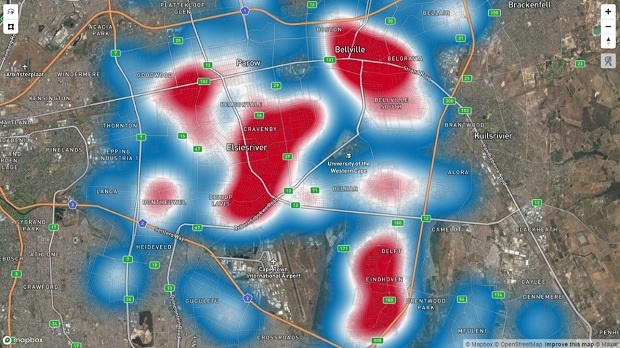

This is where Cape Town’s Covid-19 ‘hot spots’ are

In the broader province, Witzenberg and Drakenstein in the Cape Winelands were also identified as hotspots.

All these fall in the province with South Africa’s highest number of Covid-19-positive cases – and deaths.

On Saturday, Tygerberg – leading the metro in cases by district – had 2 030 positive cases according to the province’s dashboard.

Bright red on the province’s “hot spot” map provided this week included Bellville, Elsies River, Eindhoven, Cravenby and Delft.

Tygerberg district. (Supplied by Western Cape government)

Is this district now gripped with fear? Or is life “business-as-usual”?

We spoke to a dozen locals, from many walks of life.

(Photo by Jan Ras)

A pharmacist at a small independent pharmacy on Voortrekker Road, a busy, cosmopolitan hub, said in her experience, life hadn’t changed much there.

“No one is worried – you can see for yourself! Nobody is abiding by the rules,” she said.

The pharmacist, who asked not to be named, told News24 that sales of proactive health products had soared – including vitamins, cold and flu remedies and natural medicines.

“And we are still serving our normal clients – for their diabetes, hypertension, etc. But this place needs to be sorted out,” she urged.

“The first week under ‘lockdown’ was brilliant. But from week two, it got worse. And when they opened up Level 4, public behaviour got even worse.”

The pharmacist said most of their patients were not South African citizens, and were typically from other countries such as Somalia, Ethiopia, India and Bangladesh.

(Photo by Jan Ras)

‘I’m scared’

Out on the streets, Wayne Scholtz collects scrap metal, by bin-scratching. He chose to collect scrap metal – such as discarded cooldrink cans, because the public would not give him money. But this meant he touched hundreds of other people’s rubbish, every day.

“I’m scared, very scared of the coronavirus. So I use plastic gloves, and a mask – then I don’t worry about the virus,” he said. “Dan’s ‘it orrite (Then it’s alright).”

Another medical professional, on the front line as an essential service worker, is Dr Paul Mkhwanazi. As a dentist, he spends his working day up-close-and-personal with patients – who have to take off their masks.

“Obviously, I still have that fear. The coronavirus is a serious problem, and it kills, for real. I do get scared. This is a threat, this is a killer, coming for us. But we are following all the infection-control measures.

“But wearing all this – my mask, my gown, with everything in place, doing everything properly – it’s fine. We haven’t experienced any problems.

“Yoh! The practice is so quiet,” he complained.

“It’s because of the lockdown. People are in their houses, there are only a few people on the street – so all the businesses are impacted. We have to pay rent, the employees… we are feeling it. But there’s nothing we can do. I’m just praying that things get better in two, or three months’ time. But we don’t know. We just pray that God eliminates this virus.”

(Photos by Jan Ras)

‘Patients are concerned’

Not far from the taxi rank, Sister Mandisa Swartz runs a small community clinic – the Cipla Foundation’s “Sha’p Left” initiative – out of a professionally-converted shipping container. There, she treats a range of patients – including patients on chronic medicine, patients with sexually-transmitted infections, “family planning” issues and everyday ailments.

“Patients are concerned about the coronavirus. Most of the patients who come here at the moment are ones who have flu-like symptoms. Even if they have a common cough, they are concerned. So I treat the symptoms with vitamins, and an anti-biotic, if there is a need for one, and then I refer those with severe symptoms to the day hospital, which is free to test for the coronavirus.

“So far, I have had two patients with flu-like symptoms. I received a phone call from the day hospital to say they had tested positive, and were in isolation. I was also tested, but lucky enough I was negative.”

Swartz said access to her clinic was partially hindered by a daily roadblock in place at the entrance to the precinct.

“Some of my patients are stopped, the police and soldiers don’t allow them to come in – that’s a problem,” she said.

(Photo by Jan Ras)

‘Where I come from, they don’t have food’

Delft resident Riaan Booys is a father of four, and was pulled off the road by police, as his vehicle was unroadworthy, with smooth tyres and other visible defects.

But he said his vehicle’s problems were irrelevant, in light of a more serious crisis: “There’s lots of people, where I come from, who don’t have food. I would say 70% of children don’t have enough food. This morning, they did not even eat.”

He believed nothing was as important as nourishment, and demanded government provide more food, and fast.

Sulaiman Harris used to do mechanical work. He now spends his day roaming the streets of the area, selling sweets. “I have to do something to feed myself,” he told News24.

“I don’t have a permit, but I’m now selling these lollipops. One for R1, two for R2. I make about R150-R200 a day. But if it’s quiet – R100, or maybe R70. If I can get other work, I’ll take it. But this is honest work. It’s a living,” he said.

On the steps of the Bellville Home Affairs office, Maku Zikhona sat on the steps, waiting to register her one-month-old boy, Sande.

“I’m very scared, because it’s killing us. And it’s spreading – a lot. That’s why I’m wearing a mask. But they are checking our temperature, here.”

But she fears for the health of her children, aged eight and five.

“They are very healthy. I’m not too worried, because they are behind the gate, in the yard. But if they go out, I get worried, because I don’t know how other people feel about this virus.”

She worries that other neighbours and friends may not protect her children as strictly as she has.

(Photo by Jan Ras)

‘We are vulnerable’

Nearby, is the City of Cape Town’s temporary facility for foreign national refugees, who moved to Bellville South from the Methodist Church on Greenmarket Square in the Cape Town central business district.

Aline Bukuru said: “We are the most vulnerable, because we are exposed. Some families are in their homes, sitting well… But we are in this situation. Therefore, because we are on the weak side, we always call out to the international community to think of us – especially in this very difficult time. We need support.”

Inside the large marquee, the 622-strong group of refugees camped side-by-side, on the ground. Asked about testing in the camp, Bukuru said: “We had a donation of some machines for taking our temperature.”

On entering the camp, the News24 team were temperature-checked, and requested to wash hands and wear masks, before entry was permitted.

“But thank God, he is still protecting us. We don’t allow people to come in – we don’t trust strangers,” the refugee representative warned. Members of the refugee community ushered the news team around the camp with utmost courtesy, as professional chaperones, and bid us warmly farewell.

Outside, a convoy of army trucks rolled out of the area for the night.