- Scientists say SA must stop its mass testing programme.

- Tests must be reserved for hospitalised patients and healthcare workers.

- Zweli Mkhize says the strategy will now change to focus testing on infection hotspots.

A senior member of the Covid-19 Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC) has accused the country’s health leadership of refusing to change its mass testing strategy in the face of serious resource constraints and a large testing backlog, even though scientists have repeatedly advised that an urgent rethink is needed.

Professor Francois Venter, head of the Ezintsha health unit at the University of the Witwatersrand and a member of the MAC, says he and other scientists cannot fathom why health authorities are sticking to a testing strategy which is not producing the necessary results.

READ | The first 100 days of Covid-19 in graphics

Until now, the Covid-19 strategy – defended by Health Minister Zweli Mkhize in an interview on Friday – involves testing patients referred from a mass screening programme, which has seen more than 180 000 people referred for Covid-19 tests so far. According to Mkhize, this has enabled the department to identify hotspots which would now be targeted with more resources, including priority testing.

But Venter and others have for weeks argued that, due to severe resource constraints, leading to low turnaround times from sample collection to results, tests should be reserved for hospitalised patients and healthcare workers.

According to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), the average turnaround time for tests is now around nine days, up from two days in April.

“The turnaround times (for tests) remain a disaster. We (scientists) have told them repeatedly to throw away the medical waste and prioritise. We’ve been saying this for weeks,” Venter told News24 on Friday.

Health workers conduct swabs with community member Mr Mashaba during intensified testing and screening in Alexandra.

Gallo Images

Two other members of the MAC supported Venter’s sentiments this week: Dr Jeremy Nel, head of infectious diseases at Helen Joseph Hospital, said the testing strategy “is not moving fast enough in the right direction”, while Professor Shabir Madhi, newly appointed dean of the health faculty at Wits, confirmed that “a prioritised approach was recommended to the minister”.

Venter, Nel and Madhi, however, said they could not comment on what took place at MAC meetings as these were confidential.

Mkhize said on Friday the Department of Health will adopt a more focused testing strategy, which would involve prioritising infection hotspots. But this is not the same as what has previously been recommended to him publicly by Venter and others. Crucially, it does not involve getting rid of the testing backlog samples, which Venter and others say is crucial to freeing up much-needed capacity in the country’s laboratories.

“Certainly, you’d want to focus on hotspots, but it’s a nice to have,” Venter said, adding that hotspots could not be prioritised above healthcare workers and hospitalised patients.

Mkhize said the department was looking into how long samples could last in storage. But the question from scientists has not been whether the samples can last in storage; rather, it has been whether samples older than 48 hours are useful to the Covid-19 response at all.

News24 understands that a meeting of the MAC took place on Thursday night. It is not clear whether Mkhize’s mooted change of approach has been formally communicated to the MAC.

‘Crisis’

Venter, considered one of the country’s foremost experts on HIV and Aids, says Covid-19 testing in South Africa has been in “crisis” for some time.

Venter and others say that the country does not have enough testing resources to continue with the programme, and that unless all tests can be returned within 12–24 hours, it is impossible to isolate positive cases in time to prevent them from spreading the virus.

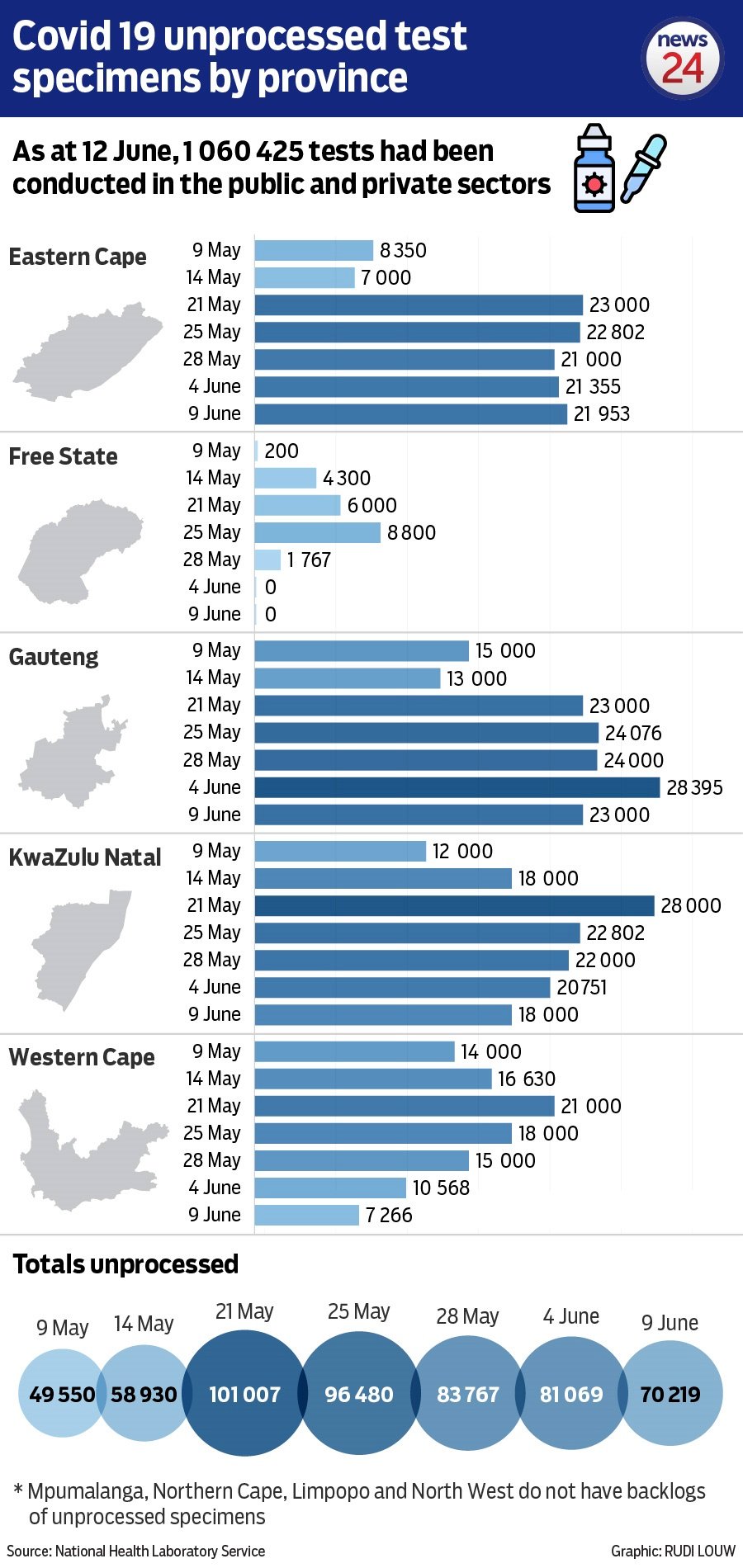

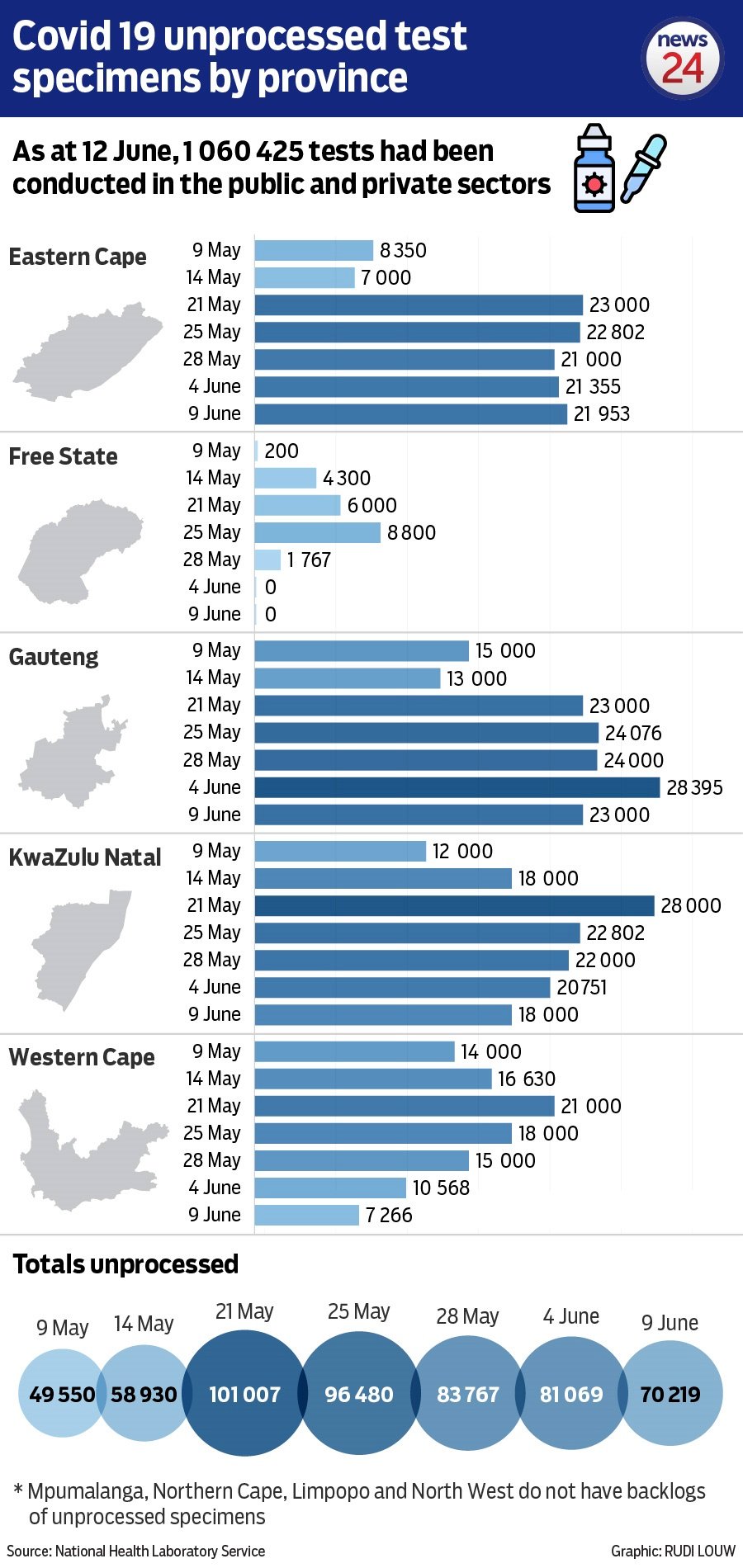

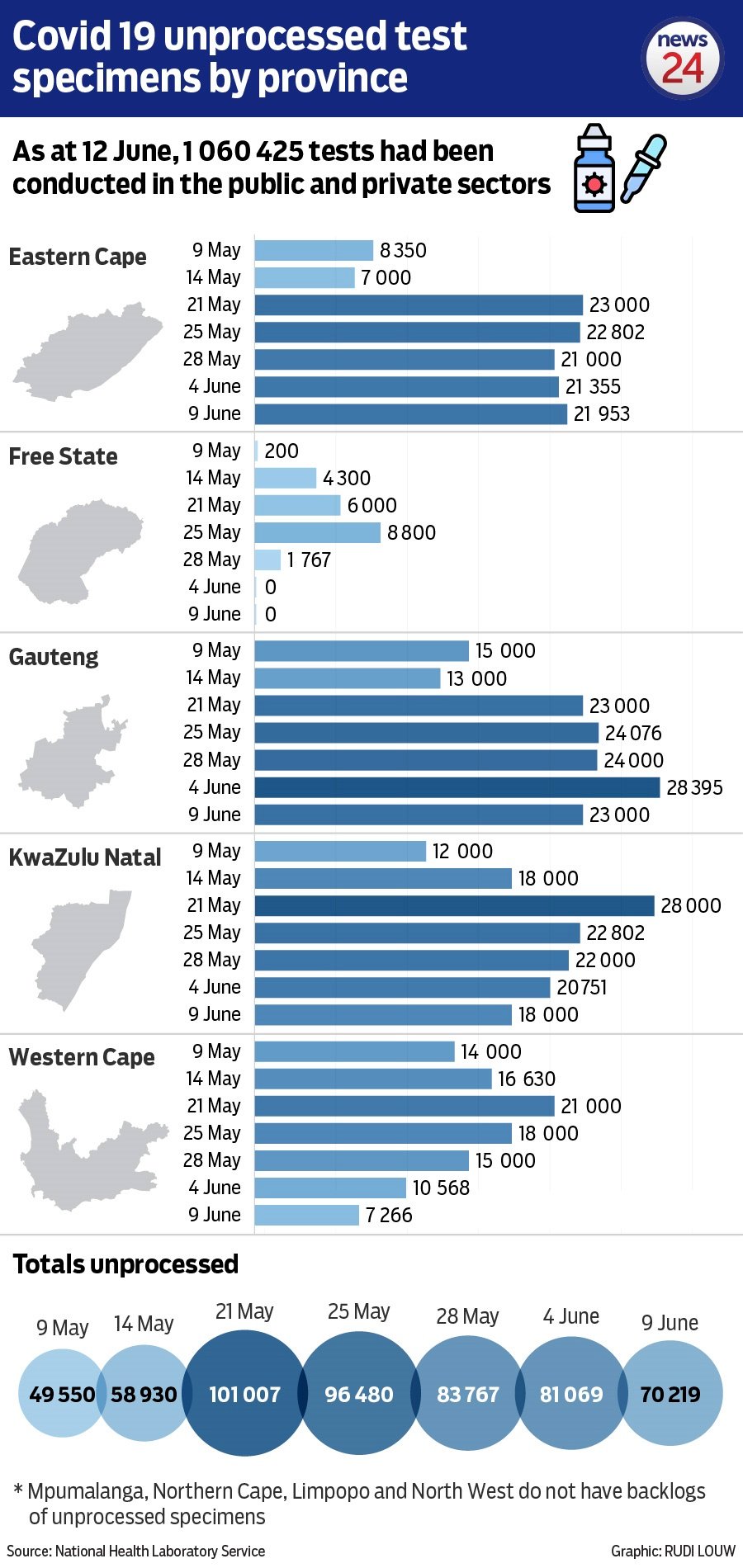

Mkhize acknowledged that the backlog was a problem on Friday, saying his department was managing this on a day to day basis. He said that the backlog, currently around 63 000 tests according to the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS), is a small percentage of the one million tests done so far.

READ | Ramaphosa concerned over ‘surge’ in violence during Level 3

The argument that Venter and others have made on various platforms recently is this: If Covid-19 samples are only processed up to two weeks after they are taken, as is currently the case, the department cannot isolate them and track their contacts in time to meaningfully impact on the spread of the disease.

Processing the thousands of “backlogged” tests effectively becomes pointless and is clogging up the system, so that urgent cases like those of healthcare workers cannot be processed quickly enough.

Venter told News24 on Friday: “We are also told they are getting on top of their ‘backlog’. Let’s be clear, after 48 hours, it’s not a backlog, it’s medical waste that must be thrown away…

“This is a crisis and it has been for weeks. I do not understand why the minister and the health department are not urgently changing course.”

The NHLS, however, say that turnaround times are improving and the backlog is being managed.

These assurances were repeated by Mkhize on Friday.

Calls for change

Venter and others have publicly said the department should urgently change its strategy to focus testing on healthcare workers and hospitalised patients.

In an article in the South African Medical Journal on May 15, Professor Marc Mendolsohn and Madhi wrote that South Africa’s testing strategy was “broken and not fit for purpose”.

Mendolsohn is a professor of infectious diseases at the University of Cape Town, and serves on the MAC alongside Venter, Nel and Madhi.

They wrote that, if SA’s mass community screening and testing programme was to succeed, cases needed to be isolated within 12-24 hours of testing and at least 80% of their contacts needed to be traced.

They made the same argument in The Conversation several days earlier.

In an article published in the Daily Maverick on 1 June, Madhi, Mendolsohn, Venter and Nel made the same argument again.

Sample

According to the NICD, the average turnaround time for tests in public labs is now at around nine days, up from around two days in late April.

Mkhize said there was some disagreement over the number of days it would take for a sample to become unreliable. Some had said four days, others 14 days, he explained.

Mkhize said that he had tasked the NHLS with conducting an experiment on simulated samples to test how many days it took before they became unusable. The NHLS confirmed this.

However, the argument put forward by Venter and others is that the samples are not useful if they are not processed within 24 hours, not just that they may no longer be usable.

Warned

Nel told News24 there still wasn’t a clear programme in place to prioritise healthcare workers and hospitalised patients in the laboratories.

Nel said:

I think it is unfortunate that the testing strategy hasn’t moved fast enough in the right direction. There has at last been some reduction in the number of low-yield tests performed, such as those in the community screening programme, and the requirement for a negative test before returning to work has also thankfully been dropped

Dr Jeremy Nel, Helen Joseph Hospital

“However, there still isn’t a clear system in place to prioritise the tests coming from key groups, such as hospitalised patients, and healthcare workers (who need urgent tests so that we know if they can return to the frontlines early). This is despite the issue being raised publicly for weeks on end,” he said.

Nel said that this was despite assurances from the NHLS that these systems were in place.

“They are clearly not broadly operational, I’m not aware of a single hospital or lab in which the promised prioritisation systems are fully functional, and, for example, a NHLS virologist yesterday confirmed that in Gauteng, these prioritisation systems have not been properly operationalised yet within any of the state hospitals,” Nel said.

Mkhize on Friday said that the issue of prioritisation of tests “was accepted”.

“The question of how quickly everyone gets to do it, that is something we have to keep working on,” he said.

Nel said: “This is frustrating because the NHLS is currently performing enough tests per day to cope with all the high priority tests that are required – and yet turnaround time for these groups is delayed due to the NHLS not being able to reliably sort out high-priority tests from low-priority ones. Results that should take less than 24 hours are taking 2-4 days in Gauteng in most instances.”

“Hospitals and essential service workers should always be prioritised ahead of community testing, since doing so makes the greatest impact on the epidemic. Only once the turn-around time for key groups such as these is under 24 hours should community testing continue,” Nel said.

Scientists have repeatedly pointed out the dangers of mass testing under testing supply constraints.

Mkhize said that several efforts are under way to diversify the testing kits used to ensure that shortages at one supplier does not have a huge impact on testing locally and he hoped that, in coming weeks, collaborative procurement efforts would increase testing kit stocks.