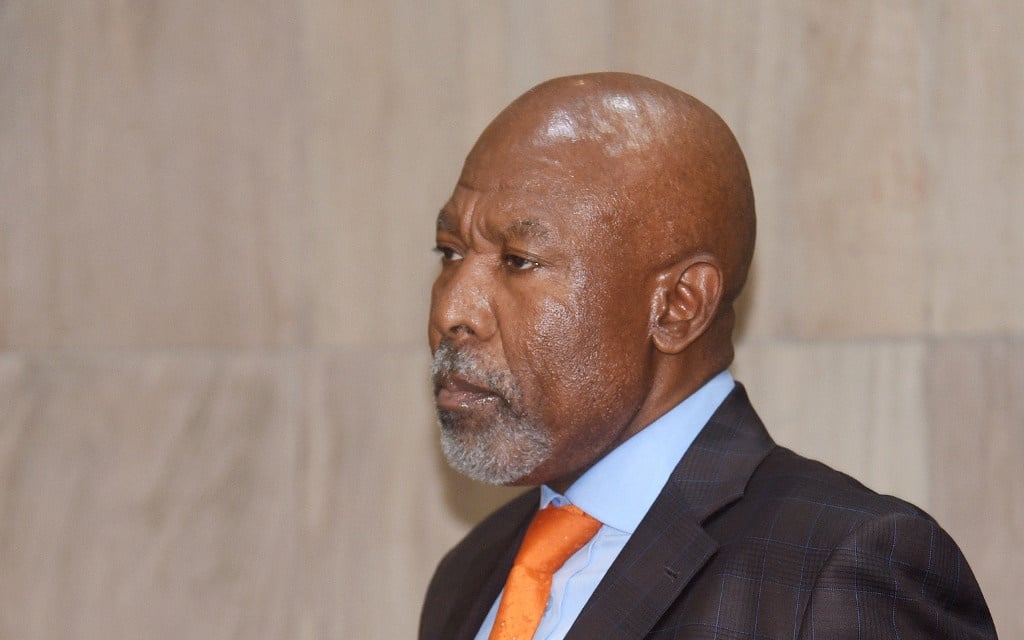

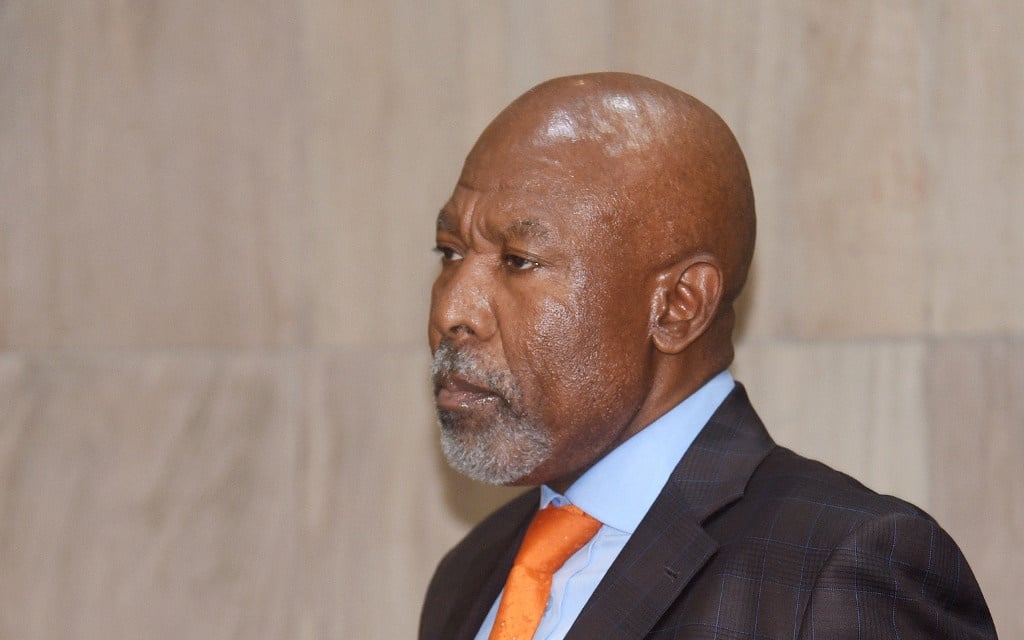

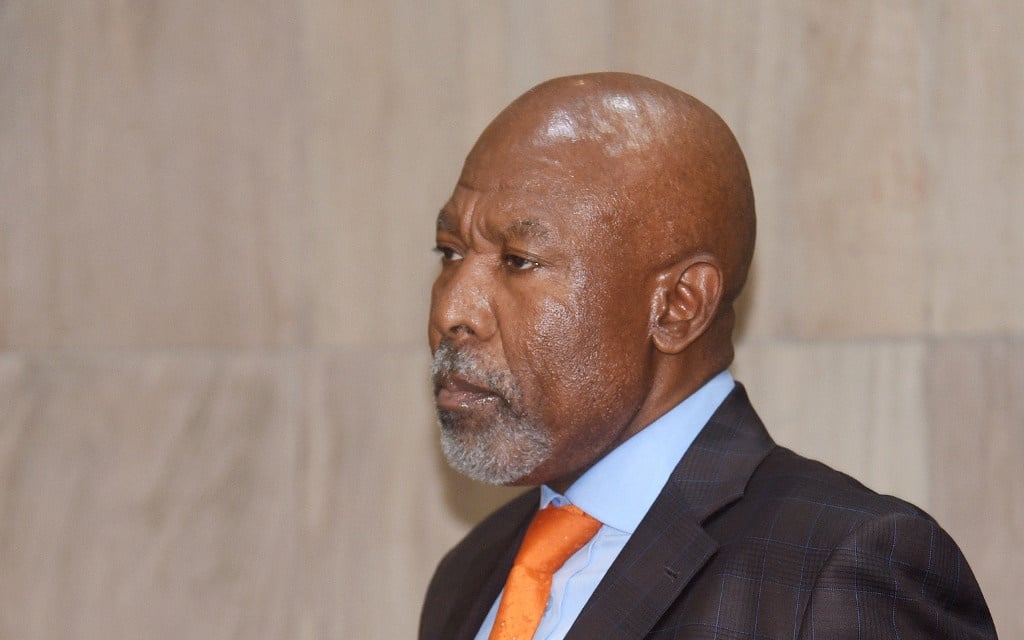

South African Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago announces a repo rate cut at central bank’s head office on January 16, 2020 in Pretoria.

Gallo Images/Business Day/Freddy Mavunda

- The Reserve Bank has cut interest rates by 275 basis points so far this year.

- Other interventions have included buying government bonds to bolster liquidity in markets, adjusting liquidity management and capital requirements for banks, and partnering with National Treasury and commercial banks to assist SMEs with a loan guarantee scheme.

- The country’s current interest rate of 3.75% – is at levels last seen 50 years ago.

- Another cut would signal growing concern on the part of the Reserve Bank.

There is still scope for the Reserve Bank to cut interest rates this year, with some economists pencilling in a 25-basis-point cut at the next Monetary Policy Committee meeting later this month. However, it is possible the bank is nearing the end of this rate cut cycle.

So far, the bank has cut interest rates by a whopping 275 basis points, exceeding the emerging market median of 100 basis points, in response to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economy.

Among its other interventions included buying government bonds to bolster liquidity in markets, adjusting liquidity management and capital requirements for banks, and partnering with National Treasury and commercial banks to assist small and medium enterprises with a R200 billion loan guarantee scheme. So far banks have loaned R10 billion out of the first R100 billion tranche of the scheme.

However, these interventions are limited in lifting economic growth, which would require structural reforms, noted Momentum Investments economist Sanisha Packirisamy. “In our view, it is ultimately structural reform efforts which need to be stepped up to improve SA’s weak economic growth trajectory.”

The domestic economy contracted by 2% during the first quarter of the year, with the national lockdown only being instituted in the last week of March. The Reserve Bank expects the second quarter figures- which will account for the full-blown lockdown which halted economic activity during April – to reflect a steep drop of 32.6%, Bloomberg previously reported. The bank estimates a 7% contraction in GDP for 2020 with a 3.8% rebound in 2021.

Packirisamy said that the SA economy would likely return to pre-Covid-19 levels in two years (2022/23), with inflation expected to remain contained in the near term, allowing the central bank to cut interest rates by another 50 basis points.

The country’s current interest rate of 3.75%, is at levels last seen 50 years ago and it’s certainly still the lowest level since the dawn of democracy in 1994.

Packirisamy said that another rate cut would be useful in providing financial relief to indebted households.

But the impact of the rate cut has not been felt by consumers to its full extent, said chief economist for the Bureau for Economic Research Hugo Pienaar. “Normally the interest rate reductions have a lag before the full-impact comes through,” he said. For people who have faced salary reductions or retrenchments, the lower interest rates won’t necessarily help. But they have helped to bring down borrowing costs which would be favourable for firms and consumers who are still employed.

Another cut would signal that the Reserve Bank’s concerns on the economic outlook have grown, he explained.

“I do think the Reserve Bank will be concerned about the real economy and inflation will remain benign,” said Pienaar. He does not believe we are at risk of a deflationary (or negative inflation rate) environment.

- READ | Inflation falls to lowest level since 2005 as Covid-19 hits consumer demand

With inflation at the lower end of the Reserve Bank’s target band (3%), Pienaar said it could go even lower, but there is no forecast that indicates it would go to zero or negative.

Similarly Investec chief economist Annabel Bishop does not think inflation will go into negative territory. Unless, oil prices collapse at a bigger rate than previously seen this year, and if there is deflationary pressure from administered prices such as water and electricity, she explained.

“Food price inflation makes up around 25% of the CPI, and is the largest component and it is unlikely to go into deflationary territory, nor is services inflation which accounts for 51.3% of the basket, and includes medical and other insurance,” she said. Investec does not expect a rate cut at the next meeting.

At the previous policy meeting in May, Governor Lesetja Kganyago noted that inflation would likely remain below the 4.5% midpoint for the rest of the year, and is expected to be “well contained” over the medium term. It is expected to remain close to the midpoint in 2021 and 2022.