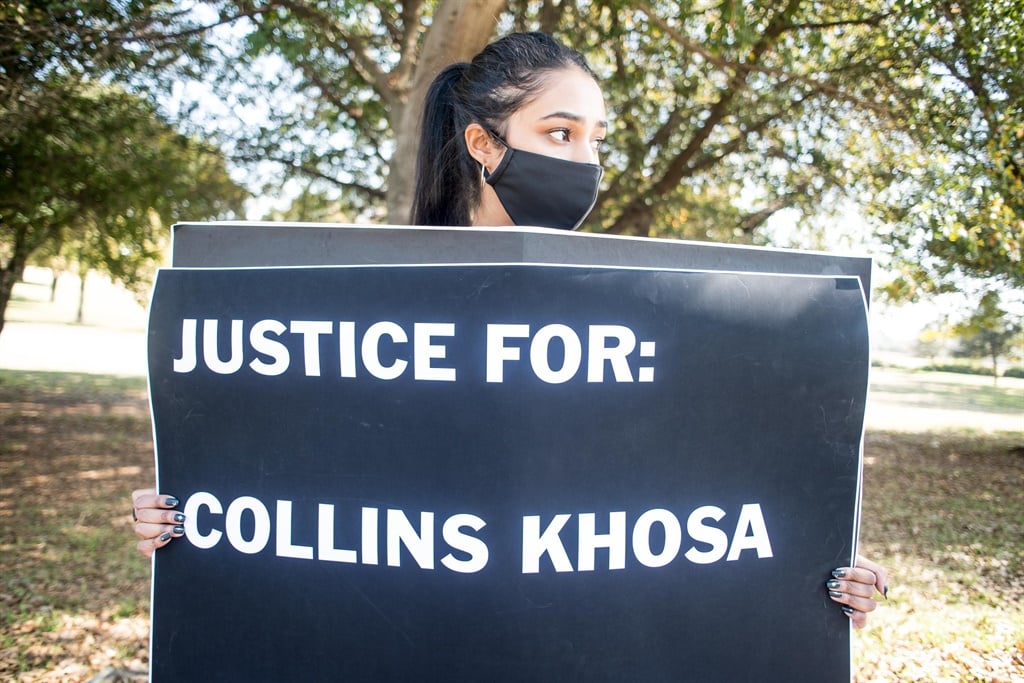

A group of South Africans protest in solidarity with those protesting the death of George Floyd in America at Zoo Lake.

When you consider the cruel and reprehensible shows of brutality meted out to George Floyd and Collins Khosa, you have to wonder if there is any place where black lives are safe at all, argues Khulekani Magubane.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, the author of the bestselling book Between The World and Me, wrote an open letter to his son in the Atlantic. In it he reminded his son that “the officer” carried the power of the American state with them and the officer’s charge “necessitates” that bodies be destroyed every year.

“Some wild and disproportionate number of them will be black,” Coates wrote in the 2015 open letter. These words ring true for many at this point in the world’s history. They find resonance in South African society too.

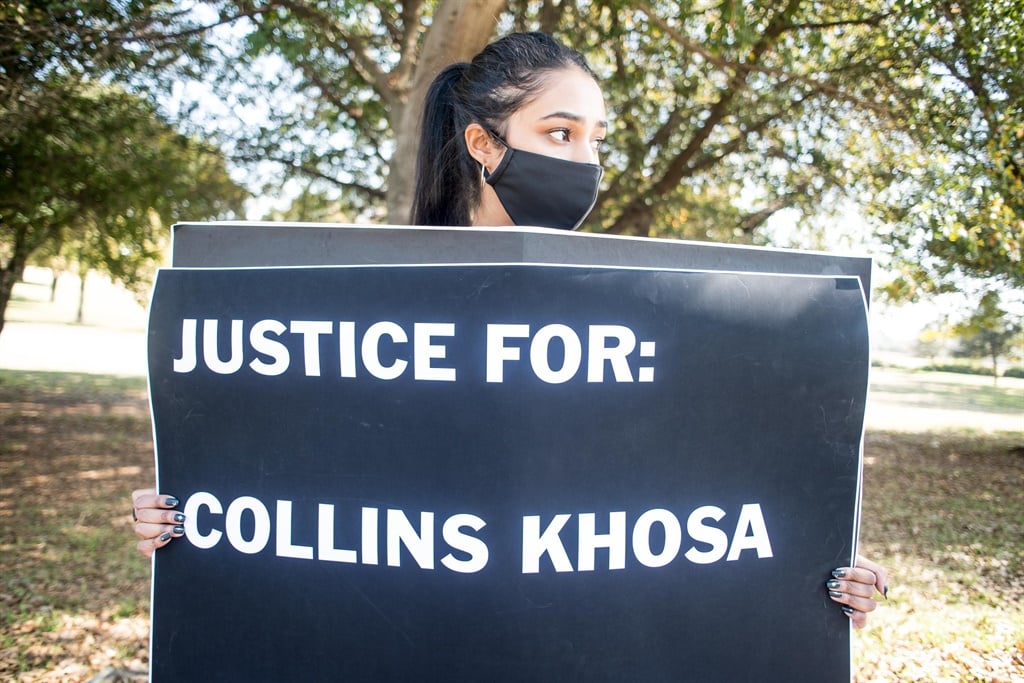

In a show of brute violence, masquerading itself as state enforcement of law and order, police officer Derek Chauvin planted his knee into the back of George Floyd’s neck. Floyd would die after that fatal encounter with the police in Minnesota in the United States.

Meanwhile, in Alexandra, South Africa, personnel in the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) and the Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department allegedly beat Collins Khosa to the point where he sustained fatal injuries.

READ | ‘Losing faith in the law’ – Alexandra residents react to Collins Khosa saga

This was done under the guise of upholding a set of rules aimed at curbing the spread of Covid-19 during our national lockdown.

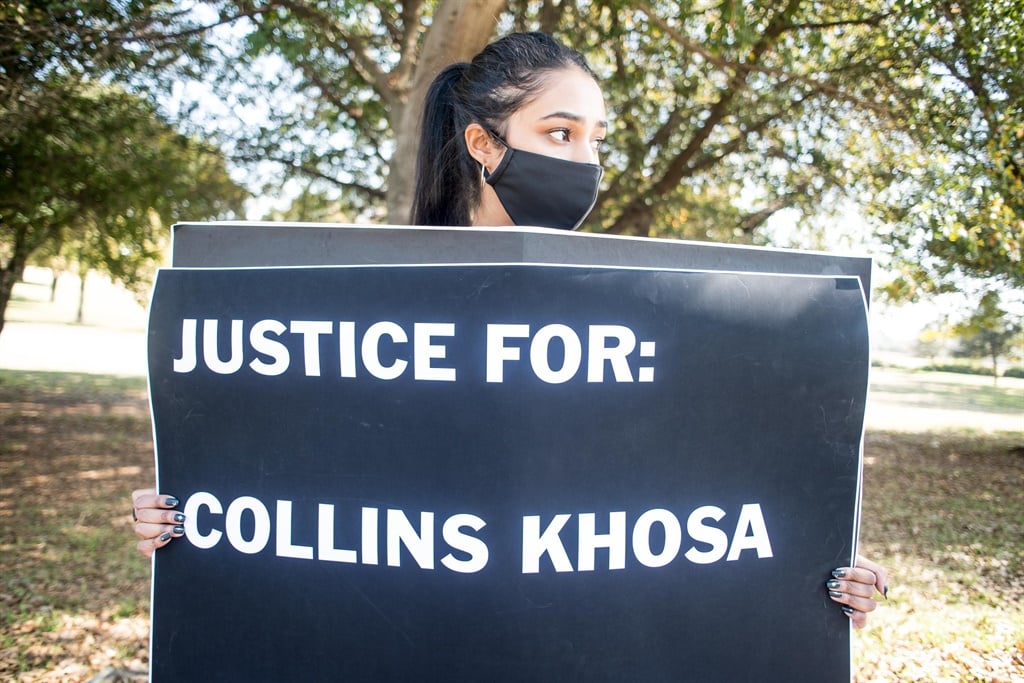

When one considers both of these cruel and reprehensible shows of brutality, one has to wonder if there is any place where black lives are safe at all. It also calls to mind the Tulsa race massacre that took place a century ago.

Demonstrators march to protest the shooting of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in the US, in 2016.

During the Tulsa race massacre in Oklahoma, scores of Americans were killed – most of them black. Black-owned businesses were destroyed in a community that was unofficially named “Black Wall Street”. Countless black Americans have now met the same fate as those black-owned businesses.

Whether it is George Floyd dying needlessly and unjustly at the hands of police officers in the US, or Collins Khosa being brutalised by SANDF personnel in South Africa, both cases show how black people are barely considered citizens by authorities when they have been disenfranchised long enough.

While court papers hold that Khosa died of blunt force trauma to the head and was beaten and choked, a report from the SANDF board of inquiry absolved the personnel he encountered of any wrongdoing in his death.

Both stories are hallmarks of lives struggling along in a world where they do not own anything. They are seen by the oppressive forces that snuffed them out as expendable, and so are many others who have met the same fate at the hands of the authorities.

As the story of Floyd’s horrific death spreads, claims have emerged that the police officers came to the scene because they were called by a shop owner who suspected that Floyd had paid him with a counterfeit $20 bill.

These claims are beside the point, but they buy heavily into the idea that black people’s character must be proven to be unimpeachable by conventional moral standards in order for them to be deemed worth of sympathy.

OPINION | Black Lives Matter in your own country, too

Let it be clear. George Floyd’s death was an injustice, not because of his moral character, but because he had the same common decency of humanity in him that all human beings have. His life was worth more than any authentic or counterfeit banknote.

The township of Alexandra, where Khosa died, is known for images of informal settlements, eroded and neglected water infrastructure and is a visual representation of government failure.

Protesters participate in a demonstration in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement and against police brutality in Stockholm, Sweden.

In houses and shacks that are homes to multiple people, at times multiple families, social distancing is somehow expected. And for these people, the punishment for disobedience is especially harsh.

This is the reality that George Floyd lived and tried to overcome. It is a world that failed to grant him his humanity, but daily forced him to justify his existence.

This is the world that gave people who look like Collins Khosa the very least, and then expected more of them than it expected of others.

This is a world where black people buy groceries from stores owned by people who look different from them; where black people save their money in banks owned by people who look different from them.

It becomes tempting to wonder if George Floyd would have still been alive if the store that he went into was black-owned.

Would Khosa have been victimised the way he was in a world where black-owned banks were common and did not issue loans to property development companies that gentrified low income communities?

One might wonder if Khosa would have died if the government and the economy of South Africa did right by Alexandra, the poor township where he breathed his last breath.

We will never know the answers to these questions. But one thing is true: when Tulsa was “Black Wall Street”, the black business owners only reached for their rifles when one of their own was threatened, and never to undermine an entire race’s right to exist.

– Magubane is a parliamentary reporter for Fin24.