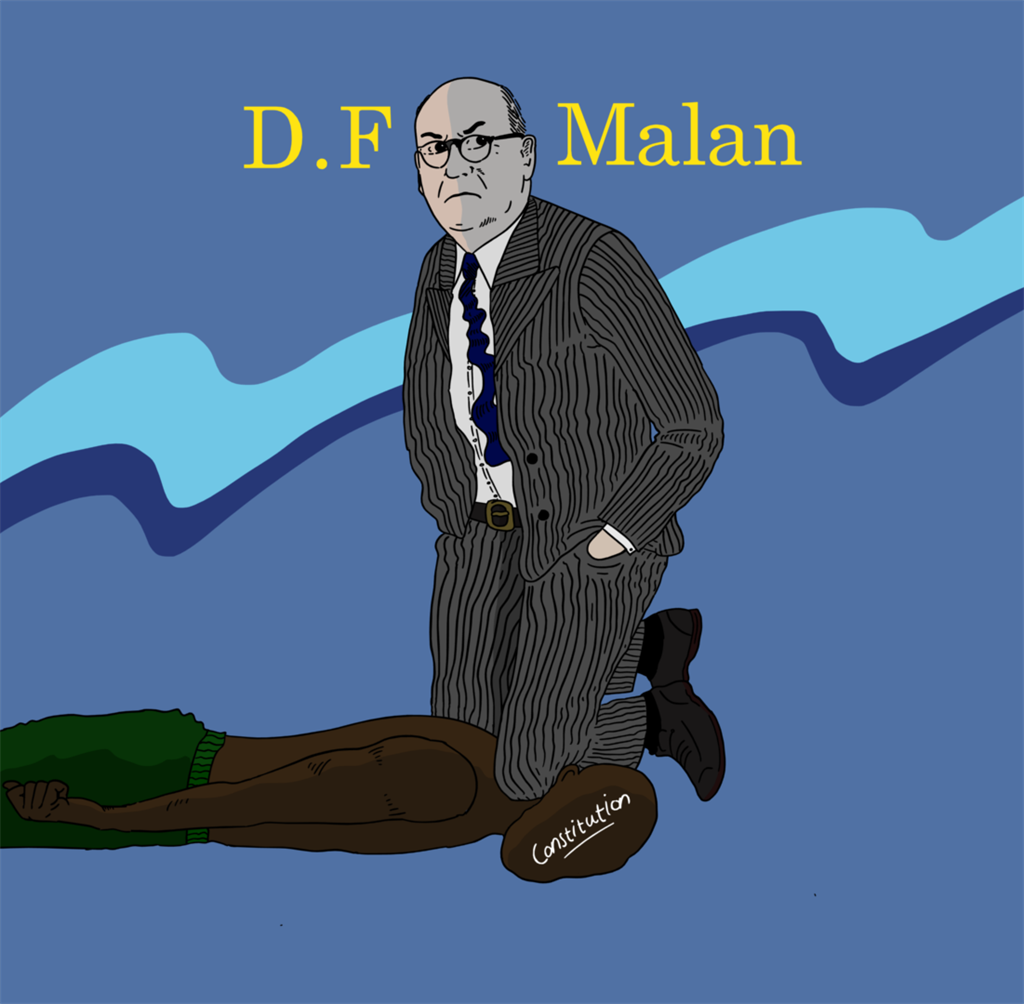

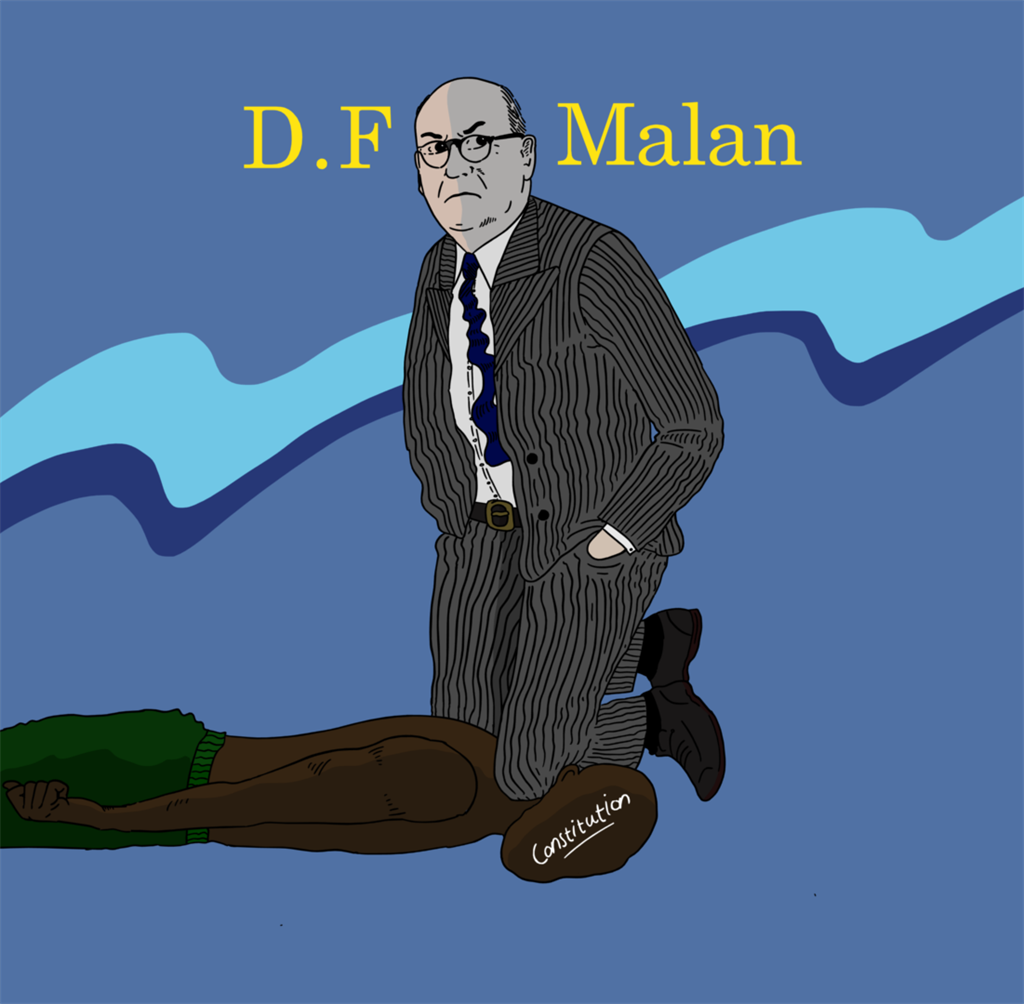

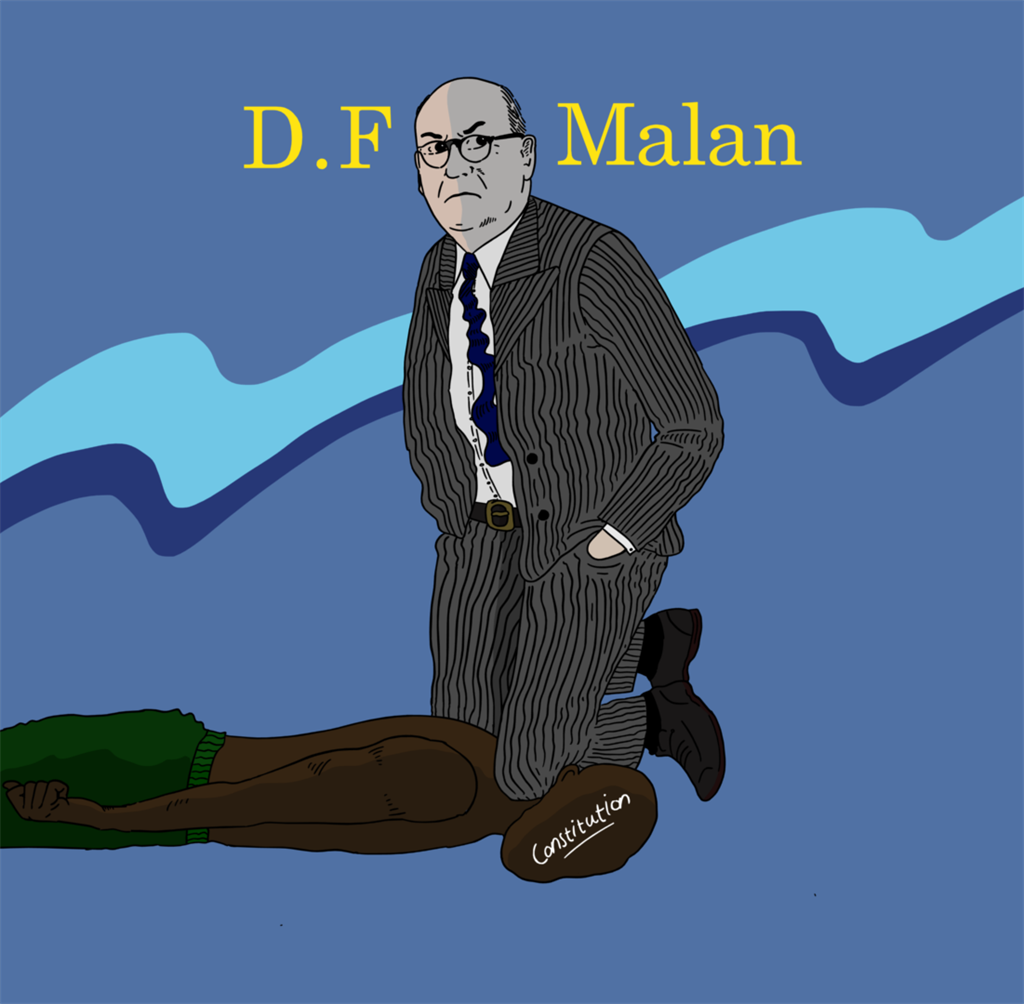

Former South African prime minister DF Malan was a champion of Afrikaner Nationalism and the first prime minister of the apartheid government.

DF Malan is not just a name. It is not just a name in the same way that Cecil John Rhodes and Jan van Riebeeck are not just names, argues Willem Muller.

When I attended Hoërskool DF Malan, an alcove in the foyer of the school displayed a bronze bust of a bald man with round spectacles. DF Malan, who sternly surveyed my comings and goings for five difficult years, co-authored notions of racism into public policy in South Africa during his tenure as prime minister from 1948 to 1954. Today, the alcove stands empty.

What does it mean that the school removed the bust unceremoniously some time in the four years since I matriculated? In these days of public protests against systemic racism and institutional racism – notably in many of Cape Town’s most prestigious schools – the question seems particularly urgent. Perhaps, and I can only speculate, it signifies a tacit admission by the school that the name DF Malan can only be countenanced if it is kept lukewarm, as it were. Old Doctor, as he was fondly known, was too much of a racist to honour with a bust, but not too much of a racist to be used as a subtle advertisement. Yes, an advertisement.

DF Malan is not just a name. It is not just a name, in the same way that Cecil John Rhodes and Jan van Riebeeck are not just names. Names of things carry meanings. Names of famous dead people evoke what they did and said when they were alive. The names of the deceased can never stand apart from who they were. This understanding is what is meant by “legacy”. In this way, Enzo Ferrari will always be remembered through the image of a sexy, beautiful, red car. And even if people forget his dour dominee-like demeanour, DF Malan will unfortunately, always be remembered for that vile construct that made South Africa infamous throughout the world: apartheid.

Illustration by Willem Muller.

Names are inherent carriers of meaning and never exist outside of context. Those in favour of naming a secondary school after apartheid’s first prime minister presumably argue that the name does not constitute bait for closet racists and sympathisers of Malan’s political philosophy. If this is the case, what does the name actually mean?

I suggest the name DF Malan, proudly displayed on two walls of the school facing public roads, is a place-holder that allows people to project ideas they endorse but cannot articulate in respectable society. When the name falls, I hold, questions about the militarism, emphasis on discipline, regressive nature of critical discourse, and institutional and unconstitutional Christian dogma endorsed by the school, all come to the fore.

This is evident in the paradoxical nature of the argument that if the name truly “means nothing”, as is often asserted by those opposed to a name change, it should be unproblematic to change it (as has happened with so many other schools named after National Party grandees, and with not a few public buildings named after DF Malan). The very fact that an argument for keeping the name exists, means that it does mean something, that there is something worth arguing for. The reasons for wanting the name are becoming increasingly evident to the world outside the palisade fence of DFM in comment sections as the issue gains social traction. Perhaps not surprisingly, these reasons veer between alt-right hate speech and profanity.

In response to the movement DF Malan Must Fall on Instagram, the official response by the school states that they do not want to have this particular conversation on social media. When I attended the school, they also didn’t wish to have it as a conversation between pupils and teachers.

He asked:

But why be scared of arguing the position for the retention of a name associated with apartheid in public?

Perhaps because it will reveal a picture of conveniently forgetful white people who hide behind weak reasoning to keep faith with sympathies that dare not speak their name: heteronormativity, racism, Christian dogma and congenial passive thinking, and their desire to inculcate these values in their offspring.

South African society will recognise the name as more than just a quaint reminder that some Afrikaners still live in laagers. South African society at large will know that when a name like this is used and defended as appropriate for a school, it signals a sinister endorsement of an environment for certain values to become part of children’s education. To many white people who argue for the retention of the name DF Malan on a school wall, it bears no more connection to apartheid. To them I say, don’t be so forgetful.

– Willem Muller graduated with a PPE from Stellenbosch University in March 2020. He is an alumnus of Hoërskool DF Malan.