Finance Minister Tito Mboweni will deliver a special adjustment budget on Wednesday, the first of its kind in at least 27 years, after the coronavirus and measures to curb its spread wreaked havoc on the economy and state finances.

The following charts show just how tough a task Mboweni faces in reviving the economy and getting onto a path of narrowing the deficit and stabilising debt.

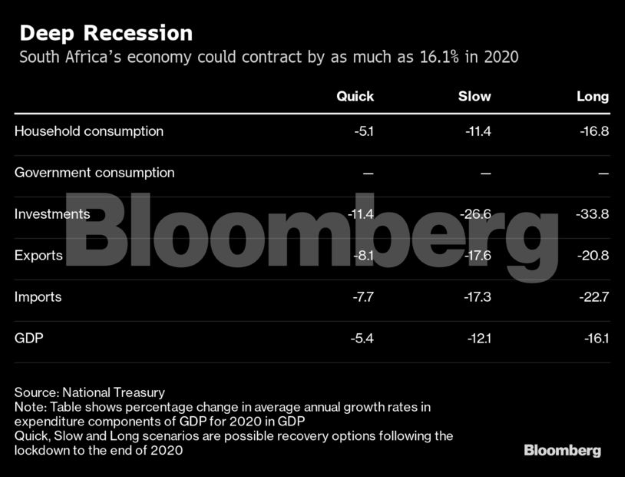

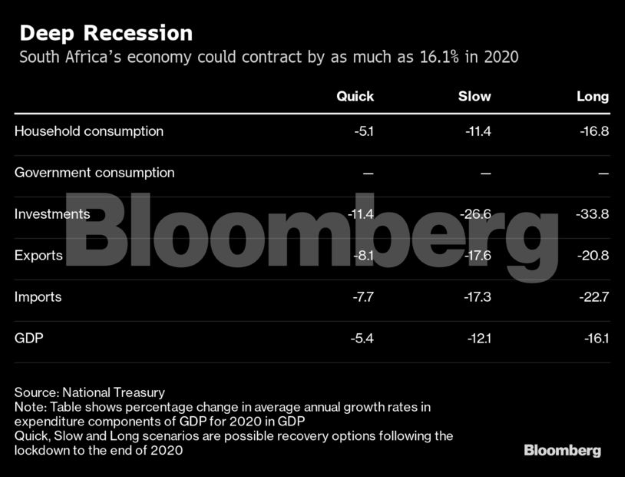

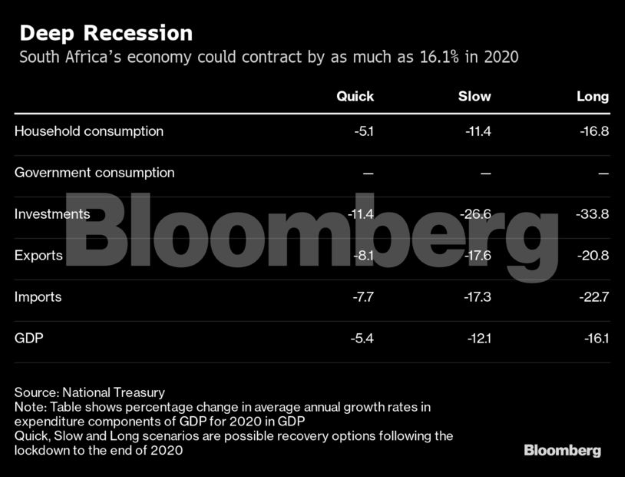

Even before the virus hit, South Africa’s economy was stuck in the longest downward cycle since WWII and slumped into a recession. Treasury officials told lawmakers in April, the first full month of a strict lockdown, that the economy could contract by as much as 16.1%, depending on how long it took to contain the virus. The central bank sees gross domestic product shrinking by 7%, which would be the deepest contraction since the Great Depression, when output fell by 6.2% in 1931. As restrictions that shuttered all economic activity except essential services for five weeks from March 27 are gradually being lifted, infections are surging.

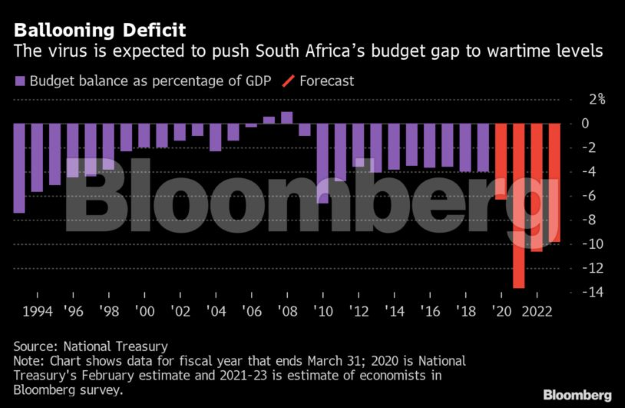

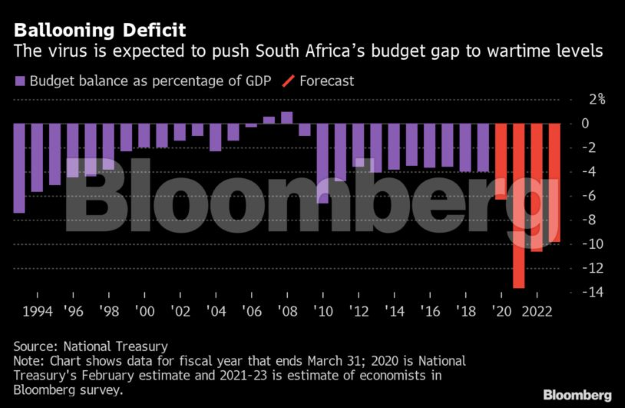

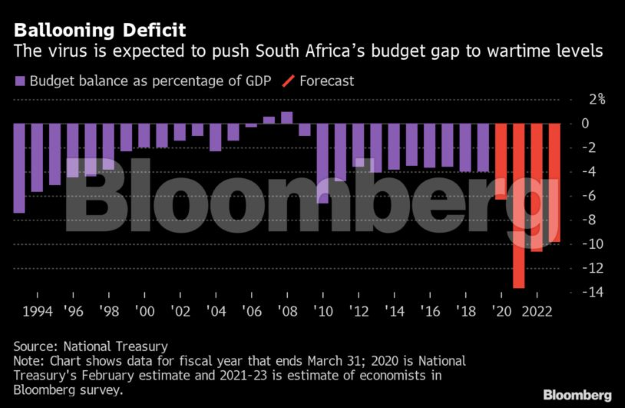

While in February South Africa’s budget deficit as a percentage of GDP was forecast to widen to a 28-year high, it’s now expected to be double that, reaching wartime levels. The restrictions hit revenue collection because many businesses couldn’t operate for several weeks while others shut down permanently. Mboweni said in April that the tax take could fall by 32% and the fiscal shortfall could swell to more than 10% of GDP, but a Bloomberg survey done this month showed it could reach 13.7%. The largest deficit on record was 11.6% of GDP in 1914, followed by 10.4% in 1940.

A key part of the supplementary budget will be redirecting R130 billion rand of spending to help pay for the R500 billion package President Cyril Ramaphosa announced in April to shore up the economy and support those worst affected by the virus. The government is counting on accessing more than $5 billion from multilateral lenders and development banks. While it’s been granted a $1 billion emergency loan from the New Development Bank, $4.2 billion requested from the International Monetary Fund has not yet been approved.

Mboweni would have to outline steps to cover expenses, either by more borrowing or tax measures. However, new or increased taxes are usually only announced in the main budget in February and higher levies could add even more strain to economic growth.

The government’s borrowing requirement for the fiscal year ending March 2021 was set at R432.7 billion before the virus struck.

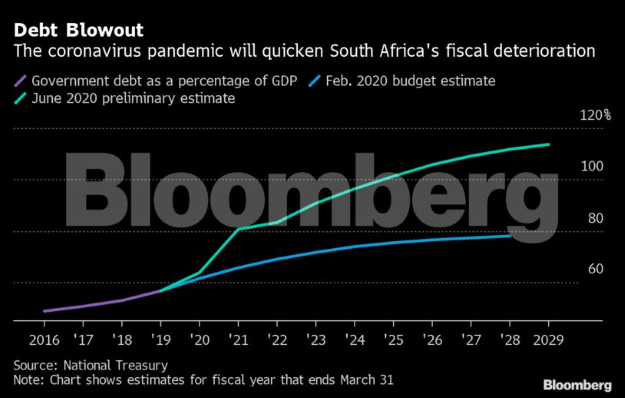

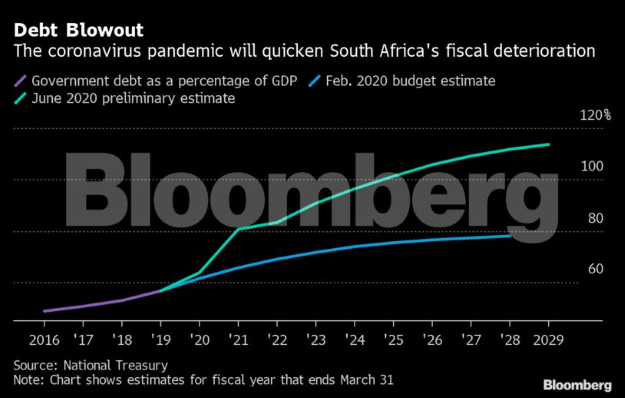

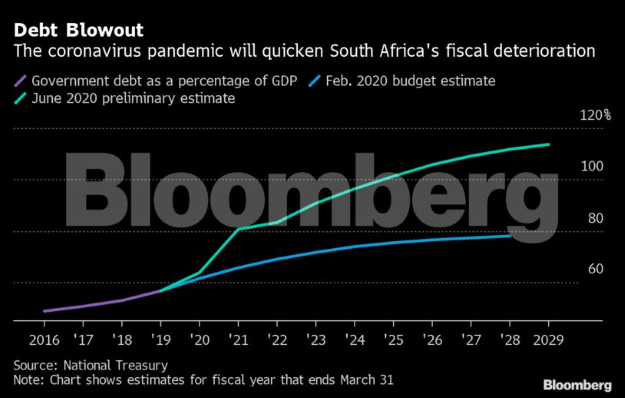

Debt levels will probably exceed 100% of GDP in 2025 and rise to almost 114% before the end of the decade, according to a document presented by Mboweni to the National Economic Development and Labour Council last week. These preliminary estimates show gross government debt climbing to 80.5% of GDP in this fiscal year, compared with a projection of 65.6% in February.

“In the short term, government will have no choice but to live on debt,” Nolan Wapenaar, a fund manager at Anchor Capital, said in an emailed note. “However, its current pace of borrowing is not sustainable and even our domestic market will, at some point, battle to finance government at the current pace of bond issuance.”

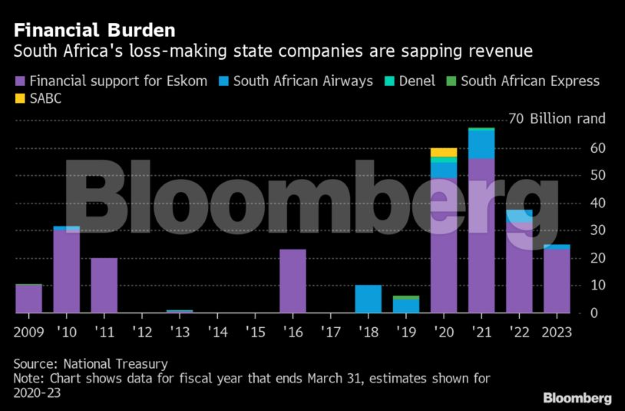

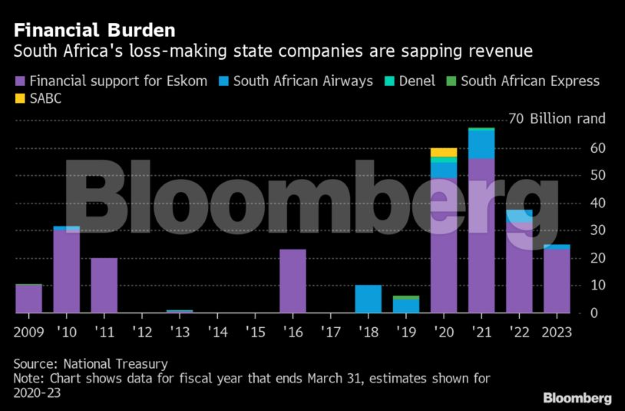

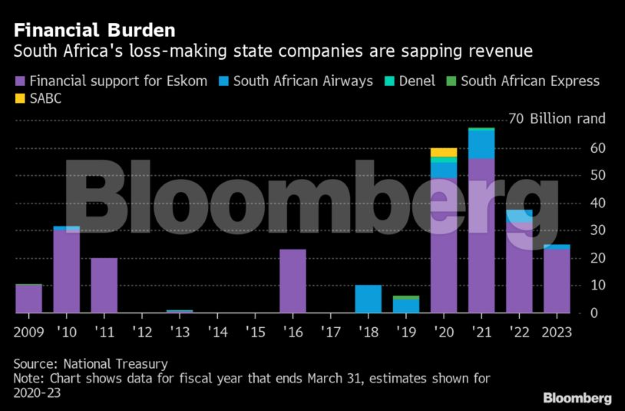

Financial support for state-owned companies may also feature in the budget, at a time when the Treasury needs all the money it can get for virus relief and to revive the economy.

The Treasury said in April that it was considering more aid for the Land and Agricultural Development Bank that is unable to repay its debt. Defaults by the nation’s largest agricultural lender could leave the government liable for R5.7 billion – a guarantee the state provided in February. Administrators for South African Airways, which is in a local form of bankruptcy protection, have proposed the government put up at least R26.7 billion to rescue the carrier after years of losses and the virus-driven grounding of commercial passenger flights.

Suggestions to deal with Eskom’s debt load of R454 billion are ongoing “and have become even more imperative as the government’s fiscal position continues to be squeezed by the obligations placed upon it during this crisis,” Investec economist Lara Hodes said in an emailed note. “State-owned entities, especially Eskom, remain a massive drag on the fiscus and are a significant sovereign credit-rating risk.”