- Finance Minister Tito Mboweni has issued a bleak warning about SA’s future if reforms aren’t instituted as soon as possible.

- The debt crises of Greece, Argentina, Zimbabwe and post-World War I Germany are some of the scenarios he sketched.

- Analysts agree with his views – but worry his reforms won’t be supported.

Finance Minister Tito Mboweni is well known for his forthrightness. And when he delivered his supplementary budget on Wednesday afternoon – the first of its kind in 27 years, according to Bloomberg – the finance minister took to scripture to issue a grim warning of South Africa’s possible future if the country did not implement reforms in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Scenarios included the collapse of Germany’s economy in the 1920s following its draining World War I defeat; the hyperinflation of Zimbabwe of the early 2000s; or the Argentine crisis of the same period, which saw that country face a four-year-long depression.

Referring to the Christian Bible, Mboweni cited the Gospel according to Apostle Matthew, which describes a “wide gate” leading to destruction, and a “narrow gate” that leads to life. For those of a faithful bent, it would not have taken much to imagine the gates of damnation looming.

To be clear, Mboweni underlined South Africa – whose total debt is approaching a record R4 trillion – would reject the wide gate, with the minister vowing to bring debt levels under control by 2023.

But analysts, while commending Mboweni for his stance, have questioned whether this would last through implementation.

“[D]omestic fiscal policy measures and implementation of economic reforms over the next six to 12 months will determine South Africa’s growth trajectory over the next several years.

“Absent these scenarios, there will be prolonged weakness in economic growth,” said Lullu Krugel, chief economist for PwC Strategy&, and Dr Christie Viljoen, PwC Strategy& economist, in a note following the adjustment budget.

Fiscal tightrope

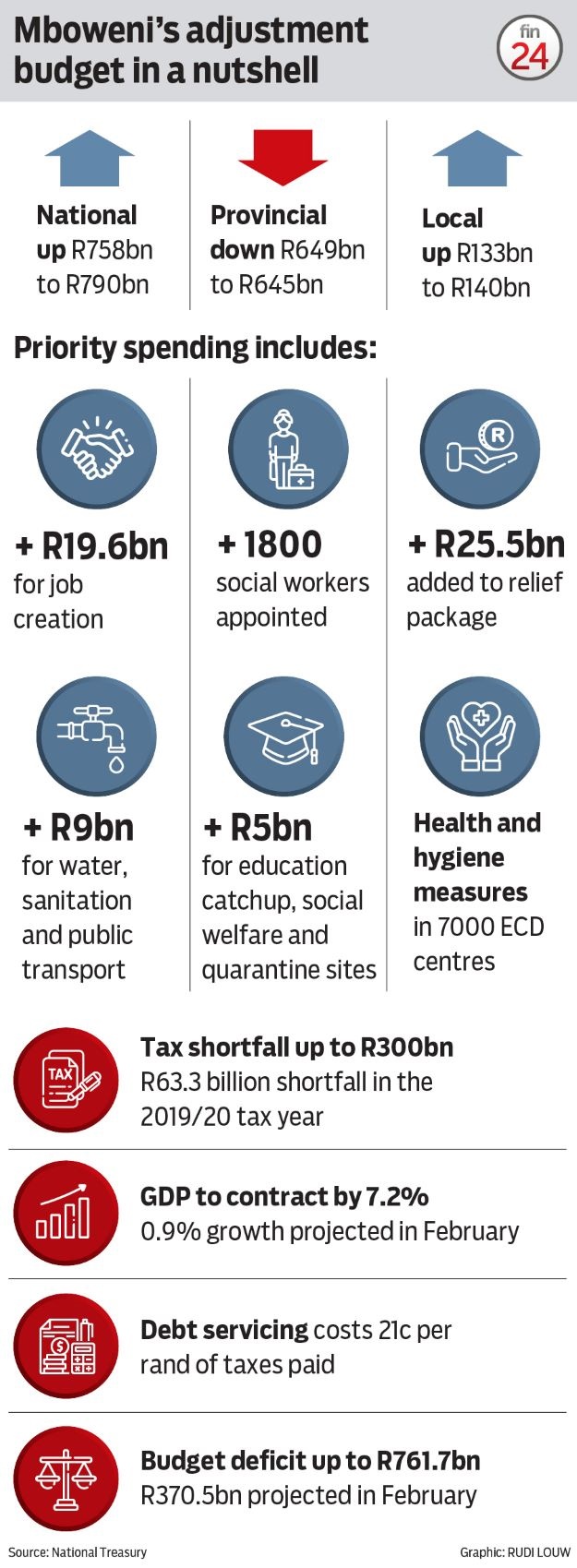

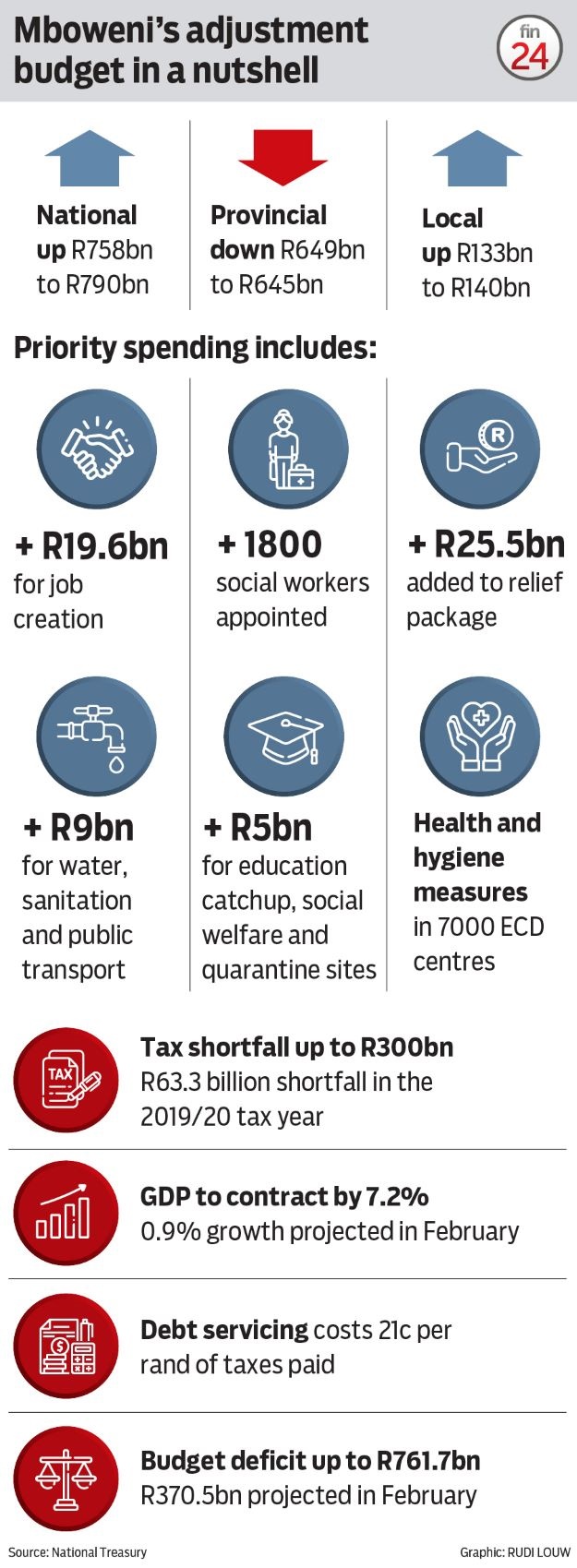

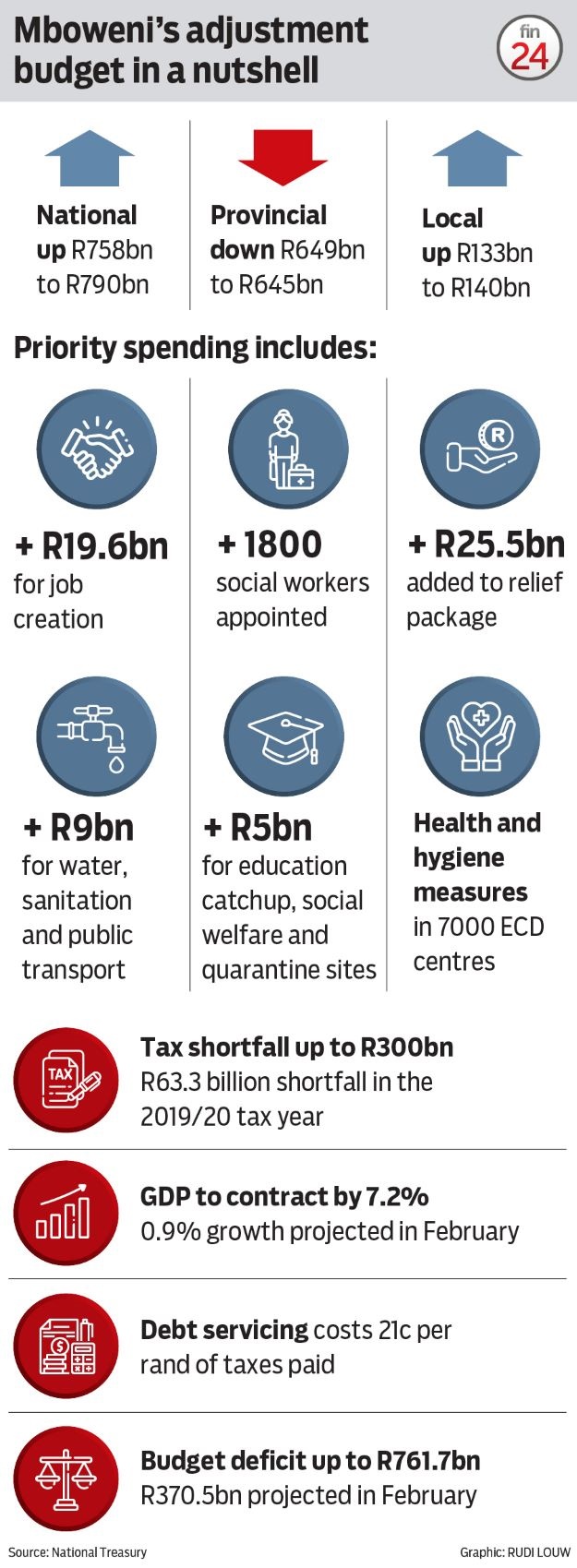

The supplementary budget was issued in the face of a fiscal tightrope. The government has had to increase and reallocate expenditure, while facing an expected 7.2% contraction of GDP – it’s worst in 90 years; a R300 billion tax revenue shortfall, record unemployment, and a looming sovereign debt crisis.

Mboweni did not mince words describing the outcome if South Africa did not rein in spending over the medium term. Citadel chief economist Maarten Ackerman described the minister as “very clear” on the need for fiscal discipline.

“The wide gate is a passive country that lets circumstances overwhelm it,” Mboweni said, adding that a wide gate opens to a “path of bankruptcy” and a “sovereign debt crisis” with “devastating” results, including skyrocketing interest rates and spiralling poverty.

In South Africa, around half of the country already lives in chronic poverty, according to some measures, meaning they have experienced deprivation over many years. Meanwhile, the coronavirus has threatened to tip another half a billion of the world’s more vulnerable people into poverty for the first time.

“We are faced, as a nation with a choice between these two gates. Even as South Africa responds to the current health and economic crisis, a fiscal reckoning looms. The public finances are dangerously overstretched,” warned Mboweni.

“If we remain passive, economic growth will stagnate. Our debt will spiral inexorably upwards and debt-service costs will crowd out public spending on education and other policy priorities. We already spend as much on debt-service costs as we do on health in this financial year.

“Eventually the gains of the democratic era would be lost.”

If action is not taken “now”, Mboweni warned, “[t]he results are devastating.

“Interest rates sky-rocket…This is what happened to Germany in the 1920s, to Argentina and to Zimbabwe in the early 2000s, and to Greece in the past few years. Argentina had its ships attached. Greek civil servants and pensioners had their salaries and pensions slashed.”

But Mboweni might find the rejection of that gate a challenge.

What his budget also highlighted is that the coronavirus response has resulted in new expenditure on, among other things, a temporary Covid-19 grant to over 18 million South Africans; a Special Relief of Distress grant for over 1.5 million adults; an allocation of another R25.5 billion to the Department of Social Development, bringing total social relief to R41 billion; R12.6 billion for frontline services; and another R19.6 billion for job creation.

All told, a combination of increased expenditure and revenue shortfall has translated to the country’s budget deficit rising to R761 billion – up from R370.5 billion projected in February.

Financing cannot be achieved simply by reallocating existing budgets. Treasury will issue shorter-dated bonds, planning over R300 billion in additional domestic bond sales. The government is also planning to borrow $7 billion from international finance institutions, and gross public debt is projected to increase to 81.1% of GDP this year, against 65.6% of GDP projected in February.

Debt-servicing costs have risen to 21 cents for every rand of taxes paid, while the tax shortfall has skyrocketed to R300 billion.

In the previous financial year, it was just over R63 billion.

So the question arises, given that the “wide gate” looms, what is the plan to address it?

In line with his stern warning, Mboweni duly promised to narrow the fiscal deficit and stabilise debt at 87.4% of GDP in 2023/24, while the medium-term budget policy statement is set to be drafted on a zero-based budgeting process – or, as Krugel and Viljoen put it, “starting from scratch”.

‘All the right things’

But Mboweni has a tough task ahead of him.

Ackerman said Mboweni had “said all the right things”, but given the depth of the revenue shortfall, there would have to be an increase in tax revenue. While some would likely come from stimulating the economy, some tax changes would be likely in October’s mini-budget and 2021’s February budget.

Mboweni’s warning of international examples amounted to being “very clear” on fiscal discipline, he said.

“What is important is that Treasury is targeting a primary budget surplus by 2023/24, which means that by then we will only spend what we can afford, excluding our interest payments,” he added. “So, we’re not going to run a deficit: we cannot spend more than we have. The aim is for debt-to-GDP to peak at about 87% and then be reduced to about 73%, through fiscal discipline.”

Krugel and Viljoen added that belt-tightening would be crucial. “Downward spending adjustments of R230 billion will be required in the next two years,” they noted in a statement.

They added a major concern was a potential lack of support for Mboweni’s envisioned reforms, as well as a lack of new ideas or implementation.

“The Supplementary Budget Review 2020 reported that the government envisions a package of economic reforms ‘that will improve productivity, lower costs and reduce demands of state-owned companies on the public purse’,” they said.

“None of these plans are new, and would be familiar to anyone who has read the Economic transformation, inclusive growth, and competitiveness: Towards an Economic Strategy for South Africa paper. The document has been around since August of last year and has not received overwhelming support (or implementation) within national government.

“This raises strong questions as to the ability of the state to reform the economy out of its recession, and in turn the ability to reduce the fiscal deficit and stabilise public debt.”