When we say “same WhatsApp group” we normally mean people share a point of view. But occasionally – very occasionally – there really is a WhatsApp group quietly coordinating what people say on social media and what happens in the streets.

In chapter 2 of “Battleground social media”, we look at how remnants of the Zuma faction of the ANC have leveraged non-profits, anonymous Twitter accounts and even an outside political party to advance their agenda. Catch up on chapter 1 here.

2017: The Black Empowerment Foundation

On 7 April 2017, 25 000 people arrived by bus, by train and on foot at the Union Buildings in Pretoria to deliver a resolute message: Zuma Must Fall.

Unnoticed, a much smaller group had gathered outside the Pietermaritzburg city hall.

Instead of slogans or demands, most of these protesters carried posters advertising the march they were already attending, which invited people “to gather in solidarity to support the efforts of the honourable president Jacob G Zuma, to effect radical economic transformation and economic emancipation by 2021”.

In the front of the group, a man in a black suit was holding a megaphone, while behind him the group of roughly 30 protesters chanted: “BEF! BEF! BEF!”

The Black Empowerment Foundation (BEF) was registered as a non-profit just three months earlier, in January 2017, and described itself as a “lobby group” fighting for “the economic emancipation of black South Africans in the greater economy”.

So new was the group, that Ibrahim Shaik – the man holding the megaphone – accidentally told police that they were from the “Black Economic Foundation”.

Shaik was not on our radar until recently, but messages from a WhatsApp group reveal he has powerful friends.

“I love this young lion in case others dont know him,” Dudu Myeni, the former chair of South African Airways, posted on the “Twitter Storm” WhatsApp group, adding: “Ibrahim….for Youth League NEC.” (More on this WhatsApp group later.)

Shaik works for Amalgamated Tobacco Manufacturing, a cigarette manufacturer in Pietermaritzburg that until late 2018 counted Edward Zuma, the former president’s son, as one of its directors.

“I am a rights activist, a human rights activist, was involved for the last eight years with Edward Zuma,” Shaik told us last month. “I also have a non-profit organisation called A Better World Alliance… I’m a politician, human rights activist. I wear quite a few caps ma’am, I’m a busy man indeed.”

WATCH:

Regardless, he was happy to set aside time to talk to us:

“The BEF was set up by Edward Zuma, Zuma’s son… I was heavily involved in the BEF in the founding stages. It’s now fizzled out… But we were quite vocal at that stage about the ANC being taken over by Cyril Ramaphosa in the manner it was.”

But there was no sign of Edward Zuma at the BEF’s protest that day or at any of the BEF’s other events. Instead he would surface amongst political notables on another WhatsApp group, that bore the BEF name.

“It’s actually better Western investors will pull back and we have an opportunity to bring them back in our own terms,” Nomvula Mokonyane, then-minister of water and sanitation, said on the Black Empowerment Foundation WhatsApp group a few days earlier, shortly after Standard & Poor’s downgraded South Africa’s foreign currency credit rating to “junk”.

“Let the rand fall and rise and emerge with the masses,” agreed Myeni, who was also on this group.

According to the Sunday Times, which published the leaked messages, the group was administered by Edward Zuma and included several ministers and deputy ministers considered to be loyalists of the former president.

Edward Zuma reportedly told the group that he had tried to block the #ZumaMustFall marches by telling metro and national police that he had been briefed there was going to be war if they went ahead.

Journalists at the time tried to get answers about whether the two groups were connected and particularly whether Edward Zuma was involved with the BEF on the ground. BEF representatives at the time either dodged the question or denied the president’s son was in any way involved with the brand-new lobby group.

When we called Edward Zuma earlier this month, however, he was in the mood to talk, and despite the BEF’s earlier denials, he was now willing to show his hand.

He told us:

I’m highly, highly involved with [the] Black Empowerment Foundation… I’m a member of the BEF, I’m a founder of the BEF and there is absolutely nothing whatsoever that could give me a reason to hide myself as to being part of the BEF.

The BEF only really grabbed headlines about two weeks after the Pietermaritzburg protest.

On 20 April 2017, members of the BEF, followed by a small group of protesters, arrived at the Point police station in Durban to lay charges against Citibank and its executives for their role in foreign exchange rate manipulation.

At the press conference that followed, Ryan Bettridge, the chairperson of the BEF, asked: “Why is the National Prosecuting Authority so quiet on these white-collar crimes while billions have been eroded from our economy, thereby affecting all South Africans, especially the poor? Are they untouchable?”

This would probably have stayed local news had it not been for the Government Communications and Information System (GCIS), which sent out an official press release announcing that BEF planned to lay charges against all the banks and bankers implicated in the scandal.

This left the GCIS scrambling to explain to journalists and Parliament why an unknown lobby group was given access to government’s official communications portal.

The BEF staged one last march in August 2017, when Shaik joined an MK military veterans group to protest the motion of no confidence against Zuma, which he described as “nothing but a scheme to unseat the ANC”.

After that, the BEF largely disappeared.

To the outsider, the BEF might have looked like an independent organisation championing worthy and popular causes like tackling apartheid-era corruption and major banks implicated in manipulating the rand.

WATCH:

But for an organisation dedicated to lobbying for transformation of the economy, the BEF spent a lot of time and energy defending just one man: then-president Jacob Zuma.

There is a name for this practice: astroturfing.

Non-profits or civil society organisations are set up to appear independent, though their goal is to lobby on behalf of particular individuals or vested interests while creating the illusion of grassroots support. Hence the reference to astroturf: fake grass.

And looking at groups like the BEF that were springing up around this time, it is tempting to ask: Did they arise from a sincere attempt to fight for “radical economic transformation” (RET)? Or did they exist to astroturf for the pro-Zuma faction of the ANC?

The president’s son explained it this way: “[O]ne of the main factors and reasons for the formation of the Black Empowerment Foundation was that we believed in radical economic transformation … and Zuma at the time was speaking the language of the BEF.”

When the Constitutional Court ruled that secret ballots could be used in the motion of no confidence vote against Zuma, the BEF decried the ruling as “yet another step backwards in our democracy” and accused opposition parties of a “pseudo coup plot”.

Edward Zuma said:

[W]e were opposing the motion of no confidence precisely because we thought and believed and still believe that the man was being targeted for his belief in radical economic transformation. Which we still believe is the case ‘til today.

But Bettridge, the chairperson of the BEF, saw it differently.

He told us: “There were individuals who thought they could utilise the public persona of the foundation for their own political ends.”

2018: The Twitter Storm WhatsApp group

The notice pinged onto more than 100 phones on the afternoon of Monday, 10 September 2018.

Dear Comrades,

This group is strictly for people who want to be part of twitter storm activities.

Twitter is our political frontier and battleground from now onwards. 1. Are you on twitter if yes please send us your twitter handle (name). 2. And if you are not yet on twitter please create an account now. 3. Or exit the group. We strictly want twitter users only. Thanking you in advance. ????

It was yet another reminder from group administrator Adil Nchabeleng that the Twitter Storm WhatsApp group was for coordinating Twitter messaging only.

Nchabeleng, the founder of lobby group Transform RSA, had started the WhatsApp group four days earlier, and in his haste had added some people who did not share his level of discipline or dedication to the cause.

Hence the reminder.

In the preceding days, Nchabeleng – who often appears in public in army-style fatigues – had been invoking military language to motivate his new troops, referring to Twitter accounts as “our online AKs”.

“We are a fighting machine here … so lets clean our battle equipment and ready our uniform and hit the battlefield ready and prepared to fight to win. There is no turning back,” he told the group on day one.

But whose war were they fighting?

To understand who Nchabeleng is, we need to go back to 2016, when he began appearing as a regular guest on the Gupta-owned TV channel ANN7 as the president of a new non-profit: Transform RSA.

In November that year, the group submitted a 130-page application to the Pretoria High Court, asking to intervene in the case which Freedom Under Law and the Helen Suzman Foundation had brought to force Zuma to suspend National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) boss Shaun Abrahams pending an inquiry into his fitness to hold office.

This was after Abrahams charged (and then withdrew charges) against Minister Pravin Gordhan and other former South African Revenue Service (SARS) employees.

According to its papers, Transform RSA was established because of concerns that “our constitutional institutions … have been vulnerable from political meddling and manipulation, political bullying and intimidation”.

The case to suspend Abrahams, it argued, was an attack on prosecutorial independence and amounted to political meddling.

Although Transform RSA’s move was widely interpreted as a cynical attempt to advance a factional battle for control of the NPA, Nchabeleng insisted otherwise:

“When you fight for Shaun Abrahams as a professional it’s factional?” he asked rhetorically when we spoke to him recently. “So black people must not be represented?”

Coincidentally, the lawyer representing Transform RSA in this case, Lucky Thekisho, also represented the SA Natives Forum, another newly-formed lobby group, when it launched a court bid to have Zuma’s corruption charges permanently set aside (see Chapter 1). We also found Thekisho’s phone number listed on the posters carried at Shaik’s march.

The Black Empowerment Foundation demonstration, held to show solidarity with then-president Jacob Zuma, was timed to coincide with the #ZumaMustFall protests that drew 25 000 protestors to the Union Buildings on 7 April 2017.

At the time, Thekisho was fighting his own court battle over another non-profit: In January 2016, the Higher Education Transformation Network had removed him as chair amidst allegations that, amongst other things, he was issuing statements without the board’s consent and on issues that were considered factional and political.

In court papers filed in October 2016, the network accused Thekisho and several other members of “issuing unauthorised statements” which led to it “being portrayed in the public domain as a pseudo-political party”.

“It is clear that Thekisho was pursuing a pro-Zuma campaign in our name,” a member of the network, who was familiar with the legal dispute, told us. They said that in their opinion Thekisho and his allies “were determined to ingratiate themselves with the powers that be at the time”.

We tried to engage Thekisho on these issues, but he responded with two combative statements.

He wrote: “I will … not participate in your self-serving prejudiced attempt at entrenching racist notions of corruption in post-apartheid South Africa. I wish to remind you that as you embark on your racially prejudiced attempt to scandalise the work of this black firm, remember that we will resist any attempts to squeeze our neck so ‘we can’t breathe’ and know that ‘Black Lives Matters Too’.

“Unless you can prove that you have investigated the role of white firms in supporting racism in the past and under our constitution, the infrastructure of racial oppression, I regard your enquiry as a racist attempt at destroying a black firm for the work it does by abusing your journalistic privileges.”

Meanwhile, Nchabeleng and Transform RSA – later with Thekisho as its deputy president – continued to champion causes and support public figures perceived as important to the pro-Zuma faction of the ANC.

To some, Transform RSA was positioning itself on the frontlines of a struggle over the nature of the South African economy. To others, the fight was a more opportunistic, factional one.

When Brian Molefe broke down during an Eskom briefing over allegations in the State of Capture report, Nchabaleng penned an open letter to the Eskom chief executive reassuring him that he was being unfairly targeted and discredited by those opposed to transformation.

When Myeni was under fire at South African Airways (SAA), Nchabaleng held a joint press conference with Black First Land First’s (BLF) Andile Mngxitama and the Progressive Professional Forum’s Mzwanele Manyi – to defend her record on transformation and call for a judicial commission of inquiry into allegations of corruption by white-owned companies.

And in January 2018, with Zuma’s presidency teetering, Transform RSA wrote to the ANC, threatening to go to court again unless it received an undertaking that the party would not even discuss removing Zuma from office.

Once Zuma was out of office, Nchabeleng and Transform RSA shifted focus to the energy debate, perceived as another site of political proxy wars.

In March 2018, they joined trade union Numsa in a last-minute bid to stop then-energy minister Jeff Radebe from signing agreements with independent power producers.

Standing outside the Pretoria High Court after their case was dismissed with costs, Nchabeleng told reporters: “Today’s judgment clearly showed that our judiciary is under capture and under influence.”

But as Nchabeleng said in his “Dear Comrades” message of 10 September 2018 to the Twitter Storm WhatsApp group, the next battleground would be Twitter. And his weapon of choice would be the anonymous accounts that make up “RET Twitter’s” loudest voices.

AmaBhungane has access to just a few hundred messages from the “Twitter Storm” WhatsApp group that Nchabeleng, the BEF’s Shaik and a handful of others created in September 2018.

Contrary to wild claims on Twitter following chapter 1, amaBhungane did not hack anyone’s devices to access this information.

At the time it was set up the group had over 100 members and had distributed a link to allow new people to join; although many, including the person who gave a copy of the messages, were removed after only a few days.

But what we have is illuminating.

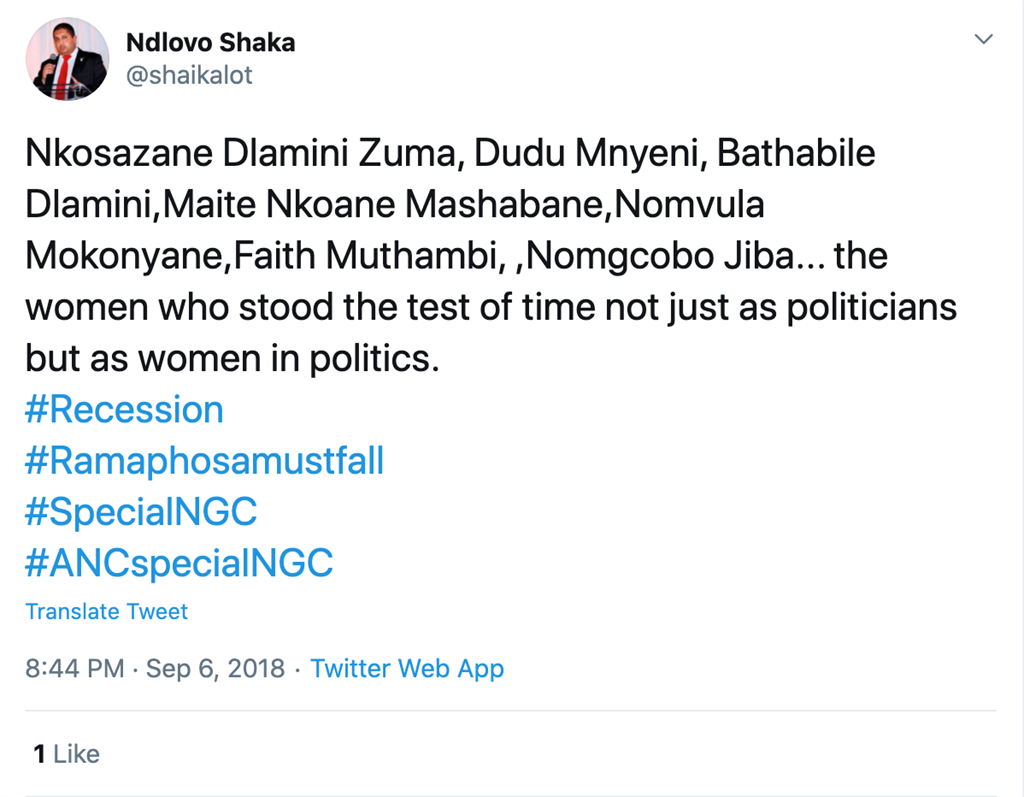

“We need Twitter activity comrades,” Nchabeleng told the group. An hour later he shared one of his own tweets, telling the group: “This message needs to trend can we share it on all groups please.”

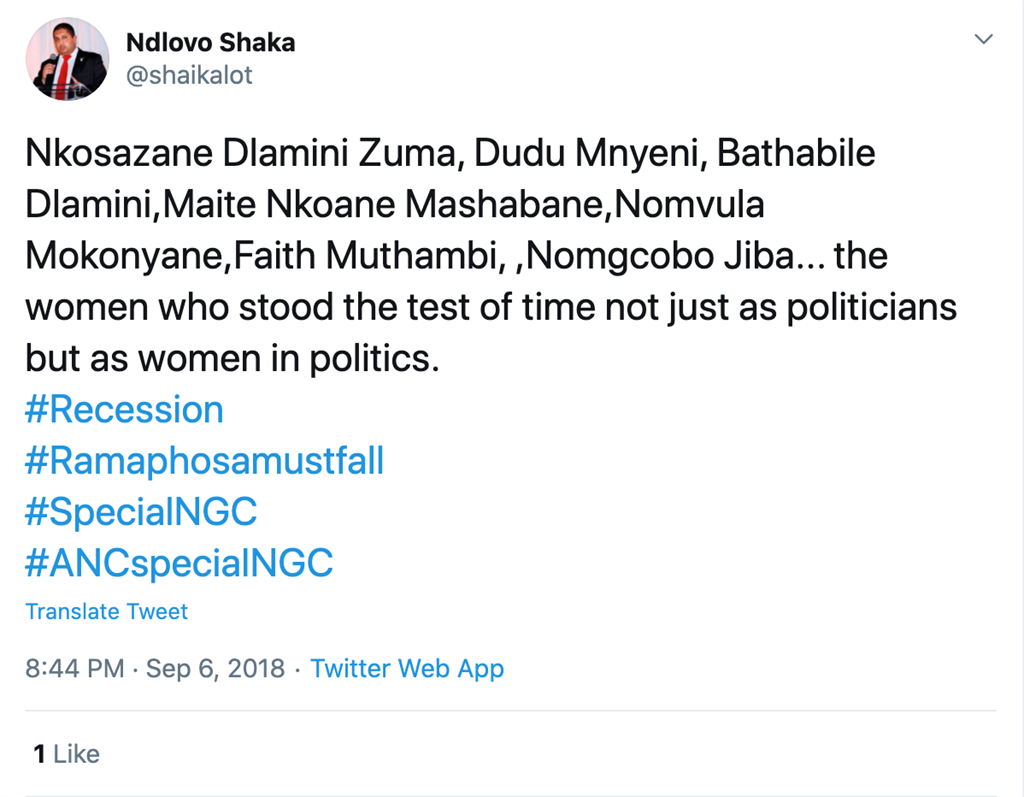

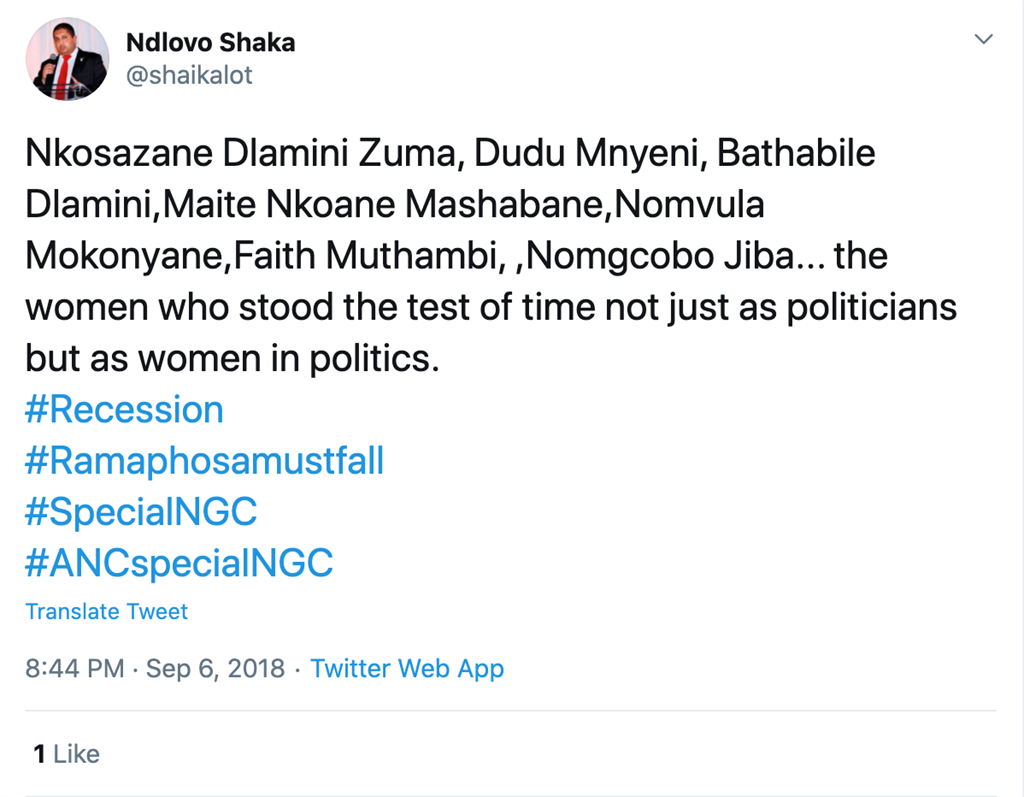

It is now 2 days since RSA officially entered a #Recession phase we have not heard a special address to the nation by President Cyril Ramaphosa seems we don’t have a president #Ramaphosamustfall ANC must call an early Special NGC [National General Council] to elect a new leader. @MYANC call #SpecialNGC Now.

Adil Nchabeleng (@NchabelengAdil

Later that evening, Nchabeleng instructed members of the WhatsApp group to gather for a “twitter storm” at 13:00 the next day: “I had very low numbers today but it was start. The hashtag to use for the entire week… are … #Recession #Ramaphosamustfall #SpecialNGC #ANCspecialNGC”.

“Well considering we not Twitter foondeez we did well,” Shaik reassured the group. “We must keep pushing till we master it. Then we will have a well oiled machine for 2019… Lets go for him tomorrow!”

Shaik was one of the few members of the Twitter Storm WhatsApp group who dutifully used all the hashtags Nchabeleng proposed.

The following morning, Nchabeleng called out a handful of the group’s “stormers” by name:

“I want to say thank you to several people on the group who made the effort to wage the twitter storm and we’re successful yesterday,” he said in reference to the #Recession campaign.

“Noli, Superblack, Charity, Shaik, Outcast, Queen and several others that braced the twitter storm and fought bitterly. We are fighting on … Today the battle will be later in the afternoon into the evening. Let’s keep the hashtags running.”

“Superblack” (@hostilenativ), as we know from Chapter 1, is the alias of Shampene Mphaloane, at the time a director of SA Natives Forum. While “Noli”, as many Twitter users would have guessed, is the anonymous account Izwe Lethu (@LandNoli).

With over 78 000 Twitter followers, Izwe Lethu (@LandNoli) is one of the most influential voices in the orbit of RET Twitter, even dwarfing Superblack’s (@hostilenativ) 33 000 followers.

That Nchabeleng had persuaded two of RET Twitter’s most influential accounts to join the Twitter Storm group seems significant.

We asked Mphaloane about Nchabeleng placing Superblack (@hostilenativ) in the middle of the group’s activities.

“So that is Adil Nchabeleng’s view,” he told us. “I will comment on the happenings of the day, and if people want to link that with whatever is being said in the Twitter storm then … it’s not for me to decide what they can and cannot do. They can make links … but I just post my own independent view… My intention was not to say ‘I am now participating in Twitter storm.’”

From what we can see, Mphaloane did not engage with the WhatsApp group and his tweets from that time give little indication he was taking instructions from Nchabeleng. He also told us that he left the group before the end of 2018.

But other prominent accounts were more engaged.

For example, when the Sunday Times ran a front-page story about ANC secretary-general Ace Magashule meeting Zuma at the Maharani hotel in Durban, Phaphano Phasha, another prominent RET activist, told the WhatsApp group:

Comrades today Sunday times is pushing serious Stratcom to divert us from the economic crisis…I suggest we focus on Sunday Times.

In apparent response, MK Military Veteran Association spokesperson and prominent Zuma loyalist Carl Niehaus tweeted that the ANC’s Jackson Mthembu was “swallowing this stratcom propaganda of the Sunday Times hook-line-and-sinker” by calling for an investigation into the meeting.

He then shared his tweet on the Twitter Storm WhatsApp group.

The following day, Izwe Lethu (@LandNoli) shared her own response: “I tweeted this as my way to respond to the Sunday Times article.” The tweet included a video of Zuma claiming that foreign and local intelligence agencies had devised a plan to “character assassinate” him.

“Can we all go online and retweet this tweet and like it please and also comment. We must always comment on the original tweet. To create the neccessary conversation,” Nchabeleng told the group.

Later, when Nchabeleng and another member of the group suggested they needed to “campaign for more Twitter users” and that the group needed “more twitter users already online”, Izwe Lethu (@LandNoli) obliged with a “Hands off our SG #WeAreWithAce” tweet.

On the WhatsApp group she wrote: “Done”.

That Twitter has become a powerful tool for political manipulation, sowing division and spreading disinformation is a given.

Because the rules governing political advertising do not apply to social media, trusted and prominent voices can be used or abused to further political aims without us knowing. Sentiments that seem spontaneous and organic may turn out to be orchestrated attempts to create the impression of popular support.

But do the coordinated campaigns of the Twitter Storm WhatsApp group fit this pattern?

When we called the woman behind the Izwe Lethu (@LandNoli) account last month, she was initially willing to speak to us but not to answer all our questions. When we asked whether she ran the account herself or whether it was run by someone else, she replied: “No comment”.

“Ms X”, who is a corporate social investment manager at a large company, is not named in this article because, unlike Mphaloane and the issues discussed in Chapter 1, her identity is not germane to this story.

We were able to confirm her real identity because Nchabeleng asked each member of the Twitter Storm group to provide their Twitter handle, in line with a suggestion from Phasha that “we monitor those who tweet in the group”.

Ms X confirmed that she was part of the Twitter Storm group, but denied there was any attempt to co-ordinate Twitter messaging.

“It’s just a WhatsApp group… There’s no mission statement there… Nobody is forced to co-ordinate and talk,” she insisted. “I’ve hardly spoken in that WhatsApp…

“If I said something would be either ‘yay’ or ‘nay’ but to actually sit down and actually do what you say I’m doing there… I have never mainly been part of some co-ordination or anything.”

We tried to ask her about the two examples above, but she hung up. We followed up with detailed questions over WhatsApp, which she received but chose to ignore.

She did, however, take to Twitter to declare herself “one of the victims” of amaBhungane’s investigation.

Nchabeleng was initially cordial and open when we spoke to him last month, saying: “I set up the group because we don’t have platforms where we can coordinate and speak about some of the campaigns we do.”

“The Twitter Storm is actually people who didn’t even know how to use Twitter. We actually created the platform to start educating on how to work Twitter, and when we have any form of information that we want to use we can always engage through the Twitter platform.

“And it has actually done quite a lot of work. It has now a presence on Twitter which is quite overwhelming. And most of it is educational around South African history, political activities and stuff like that.”

This largely squares with what Phasha told us: “I’m one of those people who engaged with Adil [Nhabeleng] to start the WhatsApp group and I don’t think there’s anything wrong. It’s just a group of people who feel that we must speak our own minds and we must not be censored and if at any point we feel that the media has a particular narrative … we must be able to tell our people otherwise.”

She added:

We started that WhatsApp group because we are being attacked, we have media houses [and] journalists who are not concerned with exposing the truth; they are concerned [with] protecting Cyril Ramaphosa.

She also told us she does not consider herself to be a Zuma supporter.

But when we read some of the WhatsApp messages back to Nchabeleng, particularly those that hinted at the group’s factional political motives, he became defensive.

“I never ever ran a campaign to say ‘Ramaphosa Must Fall’. If we did run a campaign for Ramaphosa, he will not be in power.”

Asked about the inclusion of the two prominent anonymous Twitter accounts and his attempts to co-ordinate “Twitter storms”, Nchabeleng said: “We brought them into the group to educate and actually assist people who didn’t how Twitter worked… [T]here hasn’t been any coordinated activities, and if it was it would have been catastrophic because we are really serious when we do things… we achieve results.”

He asked us to provide him with dates, times and the content of the messages we were citing, which we did.

He responded with a series of messages, accusing us of spying and engaging in a smear campaign.

He followed this up with a column for IOL accusing us of “neo-Hitlerism” and “Gestapo-style questioning” and comparing our phone call to “an interrogation in a closed room with me handcuffed to a steel table”. (To give readers the chance to judge Nchabeleng’s claims for themselves, we include the full transcript of the call in our evidence docket.)

What appears to have in part triggered Nchabeleng’s heated response was our question about whether the group’s explicit goal was to defend Zuma.

“[W]hy must black people whenever they organise themselves … be continuously called somebody else’s minion?

“I last saw [Zuma] in a rally two years ago… That was the last time, and people think there is still this continuing engagement with the man… Black people are quite capable on their own, to make their campaigns and engagements, and they don’t have to be literally given an agenda to champion,” he said.

The reality probably is more complicated than the picture of disgruntled Zuma loyalists regrouping for a counter-offensive might suggest.

The Twitter Storm WhatsApp group is a microcosm of the messy political scramble that took place after Zuma was removed as president and the emergence of what has loosely been termed the “fightback” campaign.

While the group’s members have overlapping interests, it is not a coherent campaign. Differences and tensions do exist, and signs that these allies of convenience were pulling in different directions became increasingly clear as the 2019 elections approached.

Some, like Edward Zuma, Myeni and Niehaus are long-time Zuma loyalists. Others, like Phasha, are more ambiguous in their views of the former president.

What they tend now to share, however, is a loss of influence since the transition in the ANC and the ascendance of the Ramaphosa faction.

In a lengthy written response , which he also posted on Twitter, Niehaus claimed that the Twitter Storm WhatsApp group was merely a “small, diverse, group of participants, who endeavor to promote our ideological convictions” and who “share a common commitment to support, and promote, Radical Economic Transformation (RET).

He wrote:

I do not know if all the members of the group are sympathetic to President Jacob Zuma, in as much as support, or lack thereof, for President Zuma is not a prominent part of the discussions/exchanges in the group.

Niehaus also penned an IOL column accusing us of using “apartheid regime-like tactics” in our investigation.

Granted, we only have access to a few hundred messages, but from what we can see the group’s primary purpose was political, with little discussion about issues of substance, like economic transformation or land.

Instead the messages we can see repeatedly underscored that the purpose of the group was to coordinate Twitter activity.

“Dear Comrades. This is a twitter storm group only. Meaning we discuss nothing else but twitter related activities and other program. Anything else please do not post it on this group… Remember CADRES This is for Twitter Storm only Storm, nothing else Please????… Cdes we cannot have people on the group who are non users of Twitter…” Nchabeleng told the group in a series of posts.

“Definitely, [the group] was there to co-ordinate Twitter activity,” Shaik, one of the group’s administrators, told us when we asked him about the Twitter Storm group. “But not necessarily around the topic or the agenda you’re making it seem to be.”

2019: #MoveYourVote

On Valentine’s Day in 2019, a new political romance blossomed on Twitter: The African People’s Convention (APC), led by Themba Godi, announced that it had formed an alliance with Transform RSA for the May 2019 elections.

“[W]e said that we would help Themba Godi during election time and create Twitter storms and tweets as part of the social media campaign of soliciting or getting votes… And I recall very clearly that … this was the idea behind creating a Twitter storm was to push out those tweets so that we could get as many votes as we can for Mr Themba Godi and his party,” Shaik told us.

“Adil phoned me a couple of times during the election time… He said, ‘Shaik listen, we’re going full on against the ANC, we’re tired of Cyril Ramaphosa, let’s create this buzz, let’s get this media attention out there.’”

It seems unlikely that the Twitter Storm WhatsApp group was created specifically for the May 2019 elections as the WhatsApp group was created in September 2018, five months before Transform RSA’s alliance with APC was announced.

“Whatever Shaik tells you, it has nothing to do with us… He’s talking on behalf of himself,” Nchabeleng told us when we called him a second time.

We can see that Nchabeleng and Shaik attempted to draw high-profile members of the Twitter Storm WhatsApp group, like Superblack (@hostilenativ) and Izwe Lethu (@LandNoli), into APC’s campaign by repeatedly tagging them in APC’s election material.

But we can also see that these attempts fell flat, and APC’s #MoveYourVote campaign got little traction with RET Twitter.

Godi confirmed that Transform RSA was tasked with running APC’s Twitter account for the 2019 elections. “We were trying to bolster our political muscle; it was a question of what strengths they could bring, and social media was one of those areas.”

But, he said, as far as the APC was concerned, Transform RSA would only be running the APC’s official Twitter page, not create Twitter storms to benefit the party.

“If there was co-ordination – it might have happened, might not have happened – it wasn’t something we were aware of as a party,” Godi said.

“We’re very proud of our independence as a party… When people vote or campaign for you they’ll do it for different reasons… We will never want the APC to fight any internal battles.”

Godi said that after the election, which resulted in APC losing its only seat in Parliament, Transform RSA and his party parted ways.

Shaik again:

I don’t think I’m going to make that mistake again of trying to fix the ANC from outside. I’ve tried that, I thought that by working from the outside we could fix the problem, but I must be honest with you, the only way to fix the ANC is from within the ANC.

We put it to Nchabeleng that Transform RSA’s brief alliance with APC looked like an attempt to weaken Ramaphosa’s position in the ANC by drawing votes away, but he said we had our facts wrong. “Why should we use our energy to fight factional battles? We only fight them for one thing: South Africa’s prosperity and … economic transformation.”

Said Nchabeleng: “[Y]ou’re talking about a political faction battle, which is something that does not even exist, alright? If you are talking about people in the RET, that is a policy of the ANC, it is not even a faction.”

Whether astroturfing non-profits or Twitter campaigns with anonymous accounts, there is a common thread that runs through all these interlinked stories: an attempt to coordinate and amplify voices in a way that many would regard as manipulation.

The remnants of the Zuma faction and some newfound allies have resorted to different ways of influencing public opinion and discourse.

Individually, these efforts are sometimes ham-fisted and amateurish, achieving very little.

But they may still be opaque, designed to erode trust in institutions, deflect attention from compromised political figures while rounding on others, derail public discussion and deceive.

Anonymous accounts like Izwe Lethu (@LandNoli) disseminate conspiracy theories and disinformation, from claims that critical journalists are “stratcom agents” to falsified videos purporting to show Bill Gates presenting a vaccine against religious extremism. They distribute this material to thousands of followers without consequence or accountability.

Taken together, and when driven by powerful interests, the effects of this sort of thing on public discourse and democratic norms are deep and lasting.

But if you thought the manipulative social media playbook was reserved for those opposed to the Ramaphosa faction, you have not been looking hard enough.

Coming soon – Battleground social media: How fake accounts fuelled a real fight

![]()

![]()