It’s been almost three months since Patient Zero was identified, but South Africans only got to see the data that government sees on Tuesday night, when Health Minister Zweli Mkhize hosted a briefing with the scientific modellers who build projections. And what they said was unnerving.

“We actually invited the media into a meeting of the National Health Council here tonight,” Zweli Mkhize, the health minister, almost disbelievingly said at the closing of Tuesday night’s briefing where a team of scientists revealed South Africa’s grim Covid-19 projections.

It was the first time since Patient Zero was identified on 5 March 2020 that government released the models and projections on the spread of the coronavirus on which they base their policy decisions.

And, like the one and only briefing with Professor Salim Abdool Karim, the chairperson of the Ministerial Advisory Committee on 13 April 2020, it was the scientists and not the politicians who were doing the talking.

Mkhize, having called the briefing two hours before it was due to start, seemed like he was at tenterhooks. Government has recently come under increased pressure to release more data and be more transparent in its decisionmaking process.

And that pressure increased tenfold when one of the senior scientists advising it, Dr Glenda Gray, launched a broadside and labelled some of the regulations and decisions around the lockdown “unscientific” and “nonsensical”.

The minister of health immediately sought to placate critics, spending hours on the phone well into Saturday night talking to journalists and trying to put out fires.

But government – including the department of health, the National Health Laboratory Services and other departments – have not been forthcoming with the depth of information and data so that the public might understand exactly what it bases its policy decisions on.

Scientists, working quietly in the background, have also increasingly started to demur, confiding that their ability to share information with the public and colleagues are being hamstrung and that pressure must be applied to government to ensure openness and transparency.

On Tuesday night Mkhize was made to listen as a group of medical actuaries, health economists, mathematicians and epidemiologists – all of them bar one affiliated to academic institutions – exposed the full scale of what might come to pass.

And it was bone-chilling.

Led by Dr Harry Moultrie, a medical epidemiologist, the members of the Covid-19 Modelling Consortium laid out what the available data is saying where South Africa could be headed.

And members of the consortium aren’t lightweight.

It consists of experts from the University of Cape Town’s Modelling and Simulation Hub, Africa (MASHA), the South African DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis (SACEMA) at Stellenbosch University, the Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO) at the University of the Witwatersrand, the Boston University School of Public Health in the US, and the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD).

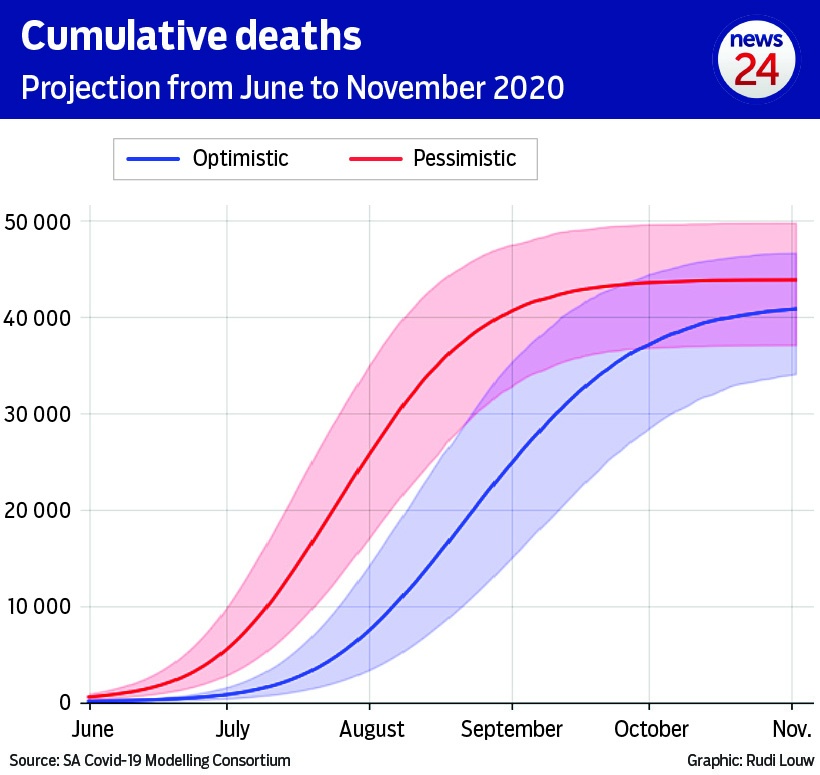

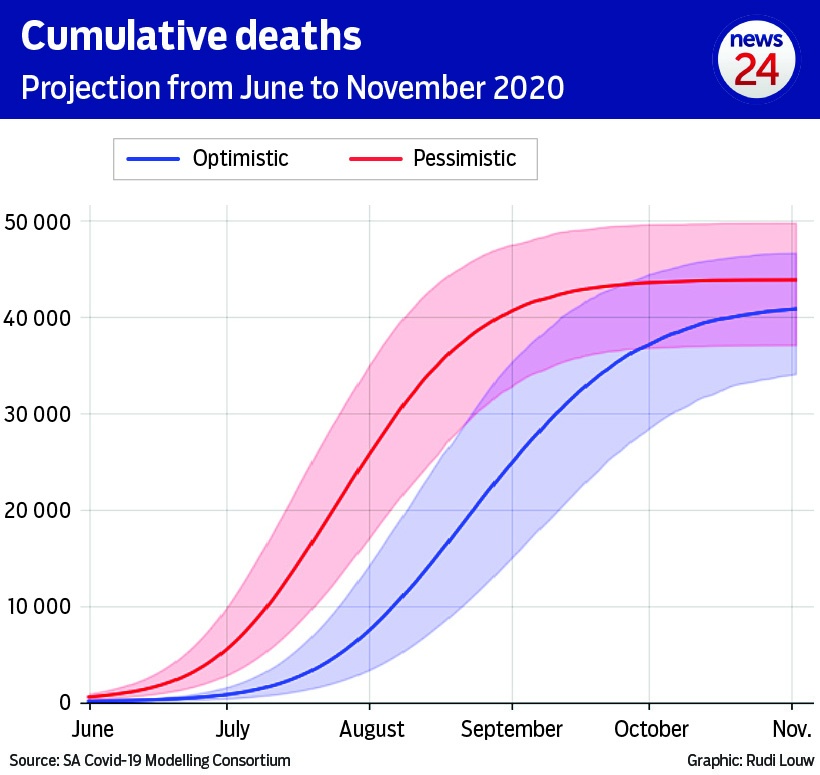

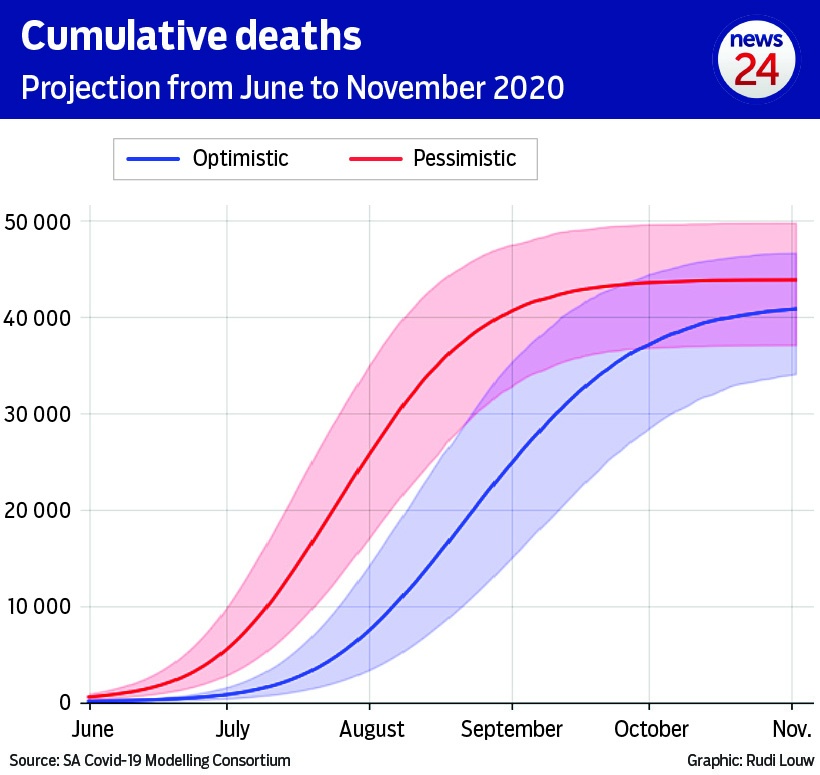

By November more than 40 000 people could die from Covid-19.

More than a million people could be infected by mid-July.

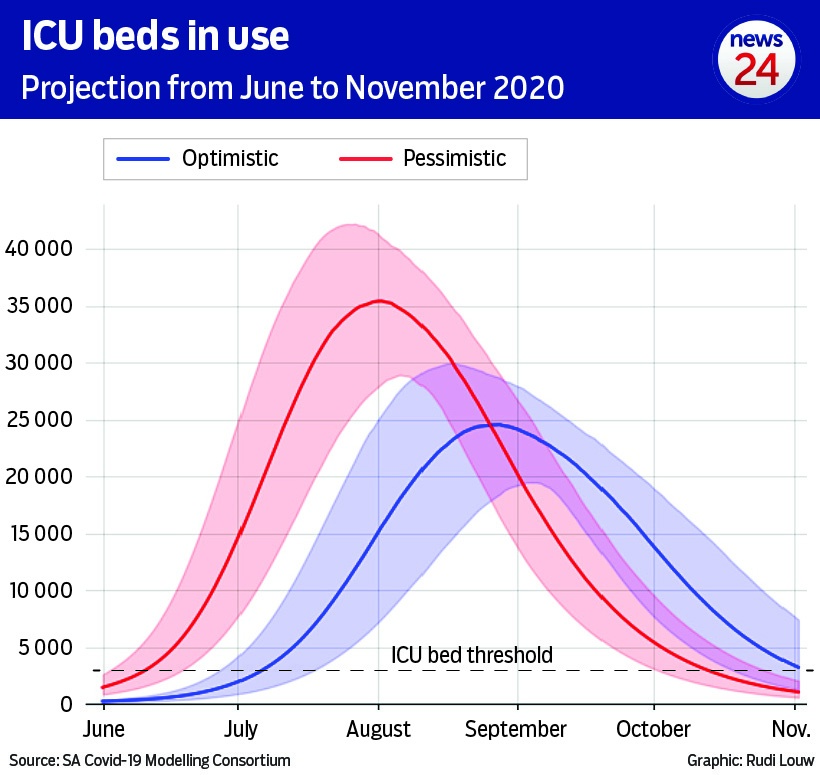

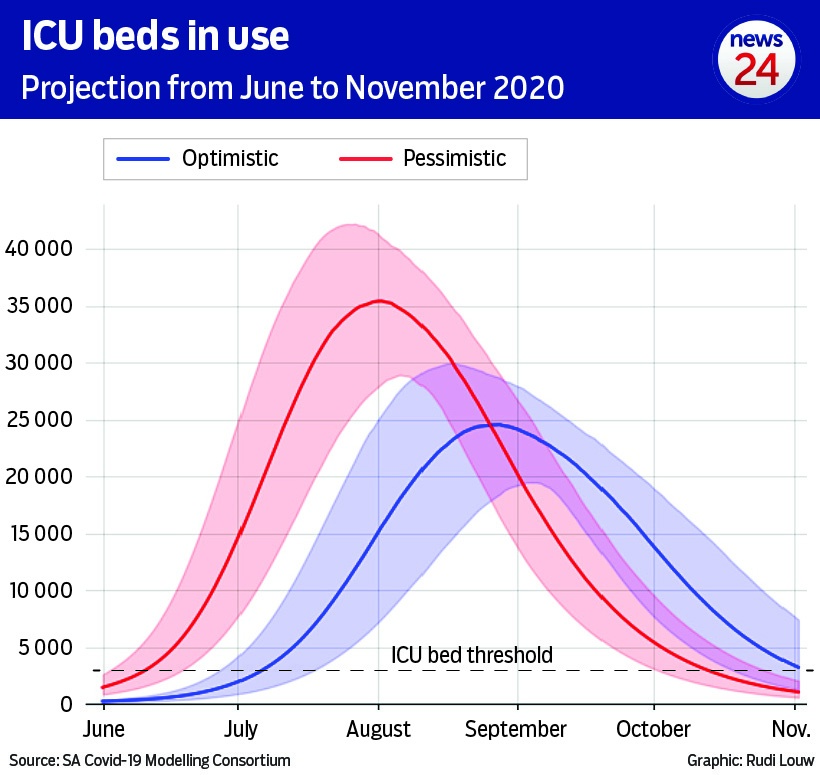

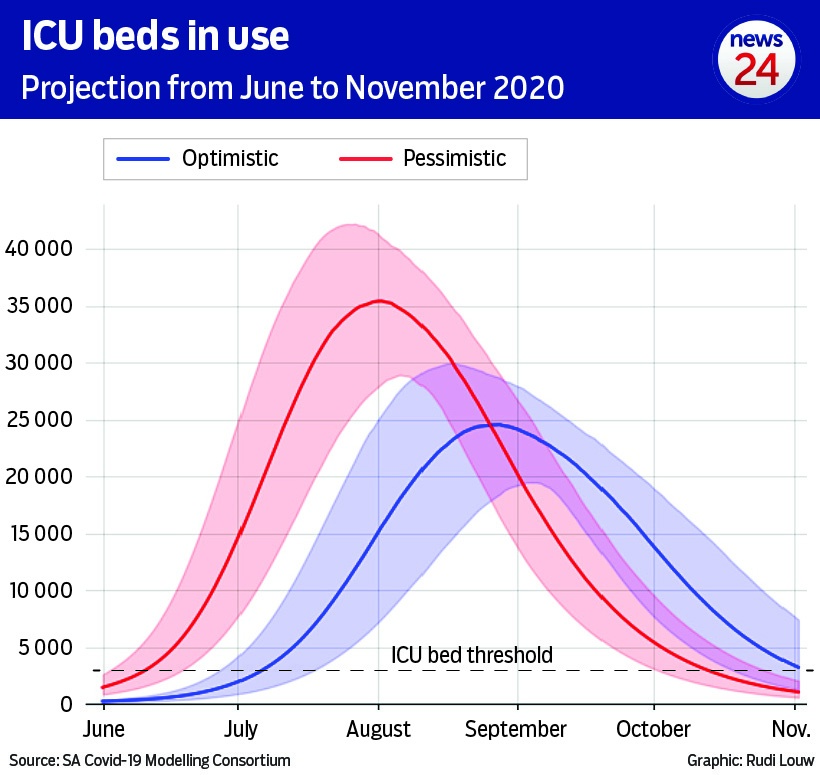

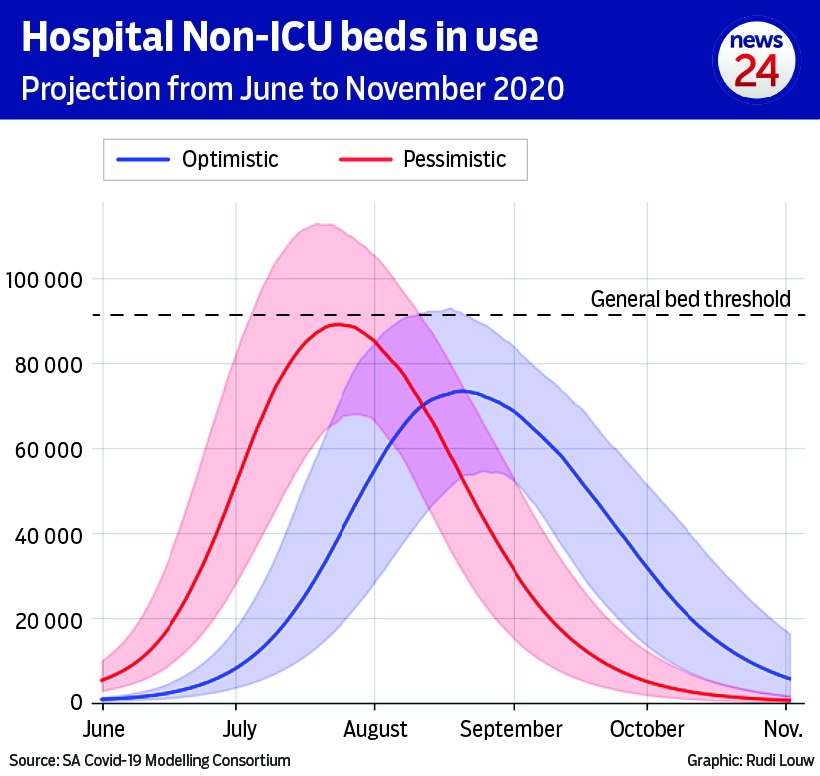

The country’s healh system could run out of ICU beds by June, or at the latest July.

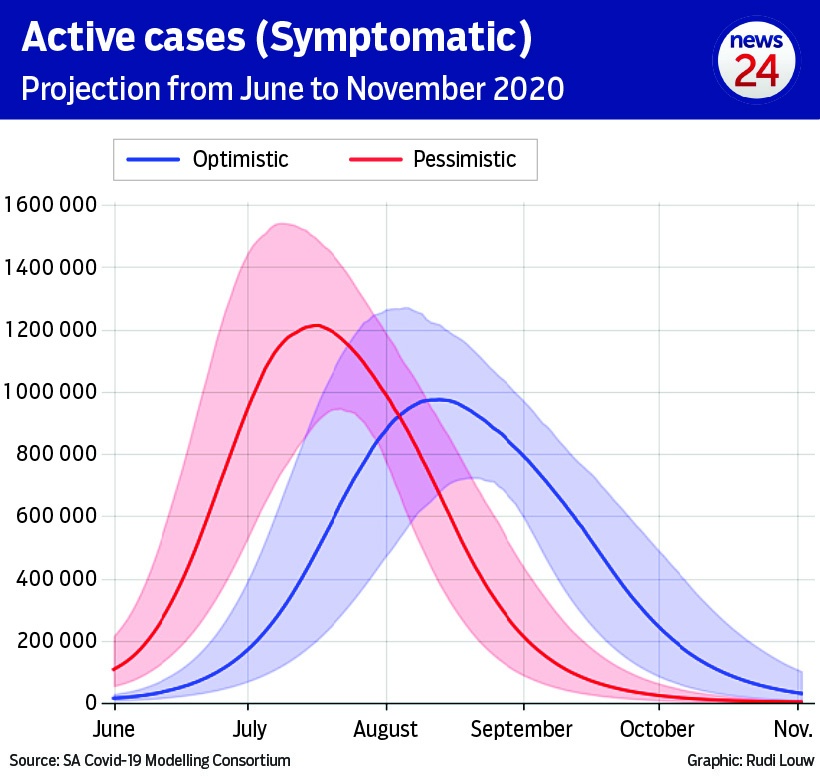

Dr Sheetal Silal, a statistical scientist whose expertise lies in the building of mathematical modelling to combat infectious diseases, clinically laid out what the long and short term projections say.

She explained the upper band and lower band of both pessimistic and optimistic scenarios, and shed light on best and worst-case scenarios.

Silal, from UCT, and her colleague Dr Juliet Pullian from SACEMA, were at pains to stress that there are numerous variables and that these models change regularly.

Pullian said the models “have their limitations, they cannot predict the future”, while Silal added, “there are considerable uncertainties, the models will change”.

But it was clear that if the rate of infection and the virus’s reproductive rate continues at the current trajectory South Africa will be in for a grim winter.

Said Silal, “There are considerable variations in the models, but our hospitals’ ICU capacity will be exceeded under any scenario.”

Dr Gesine Meyer-Rath, from Wits expanded further: “We need an increase in ICU beds by a factor of 10 … moving public sector patients into private hospitals will solve the problem for about two weeks in June, and then we will exceed the threshold.”

Moultrie, in charge of the modelling team, said it’s imperative in a democracy to release data such as these models. “If we don’t release it there won’t be space to see it, comment on it and critique it.

“The models have been scrutinised widely and we hope it will be scrutinised now. We look forward to a constructive engagement and will release the models regularly,” he said.

It’s been almost three months since Patient Zero.

South Africans have had one engagement with Abdool Karim, and one with the modelling team.

We’ve seen uneven contact tracing strategies between provinces, skyrocketing numbers in certain districts, a coronavirus command team arbitrarily announcing regulations and much conflict over the lockdown.

The models might not be perfect, and they will change. But for the first time we’ve seen what government sees. And it’s scary.