- First 100 days marked with frustration over regulations, job losses and increased hunger.

- Early success in limiting initial exponential spread of Covid-19, but expected surge looming.

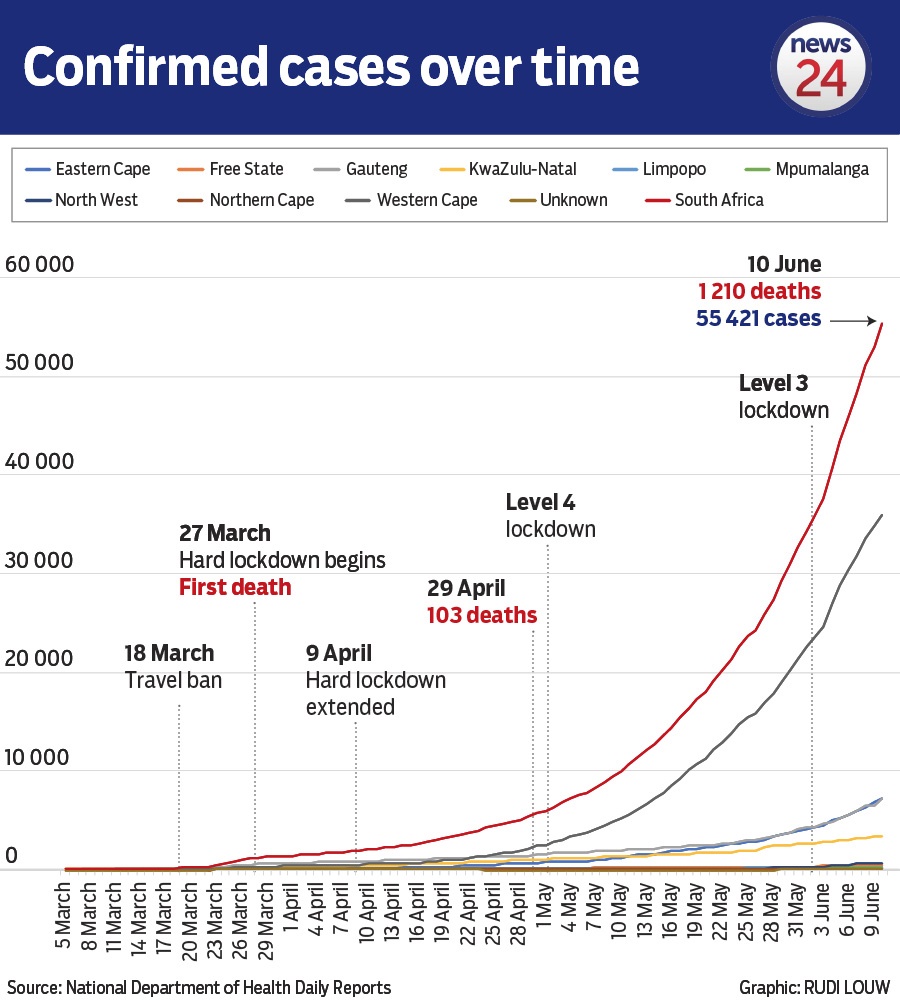

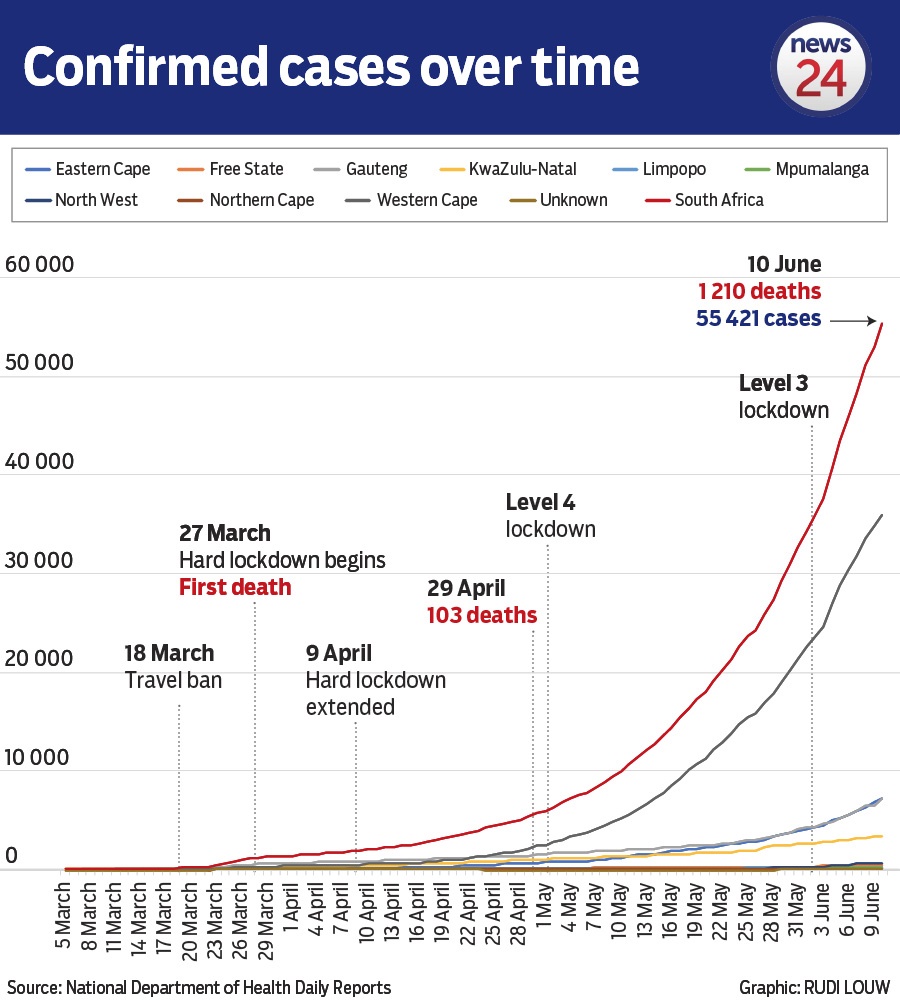

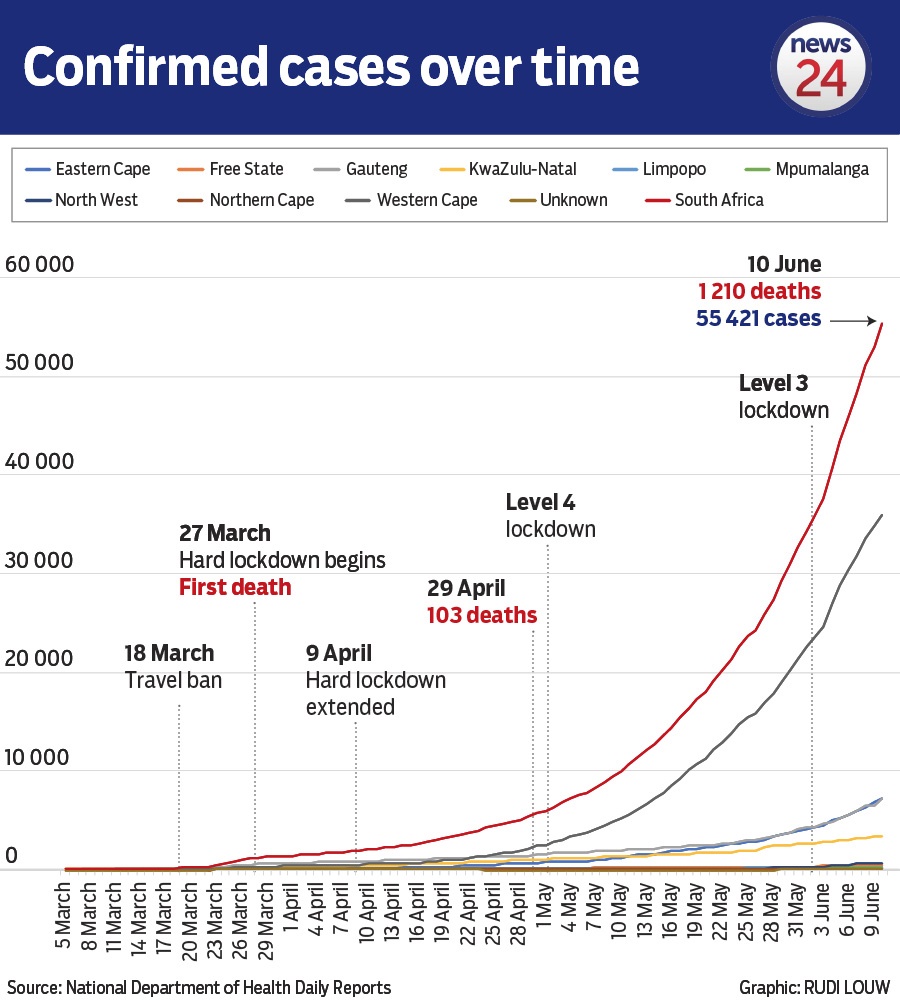

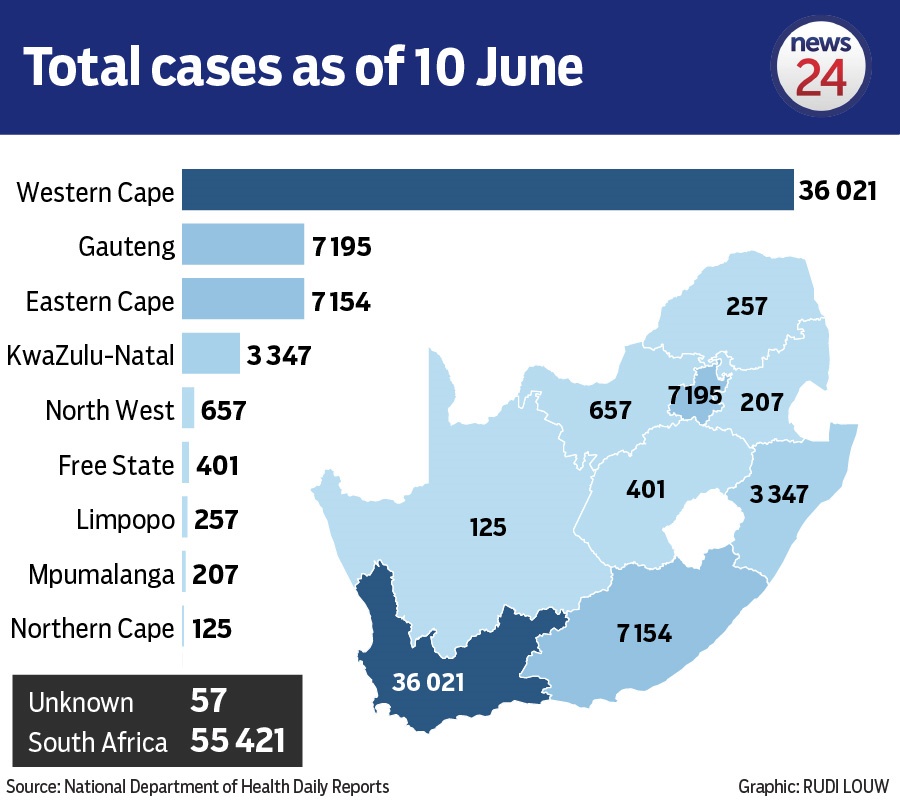

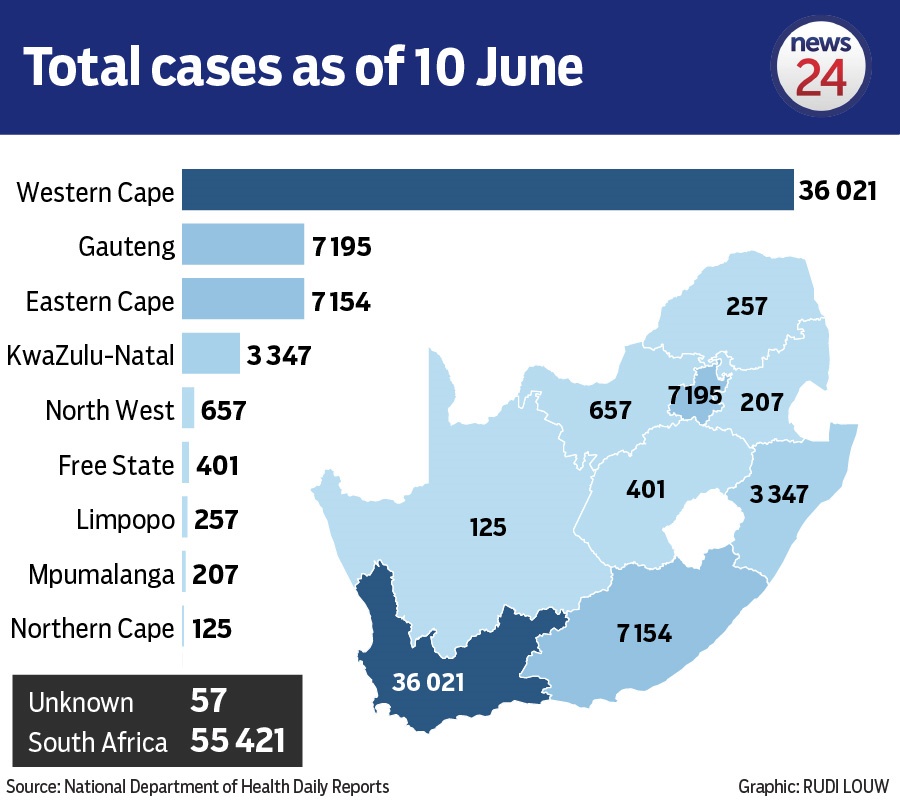

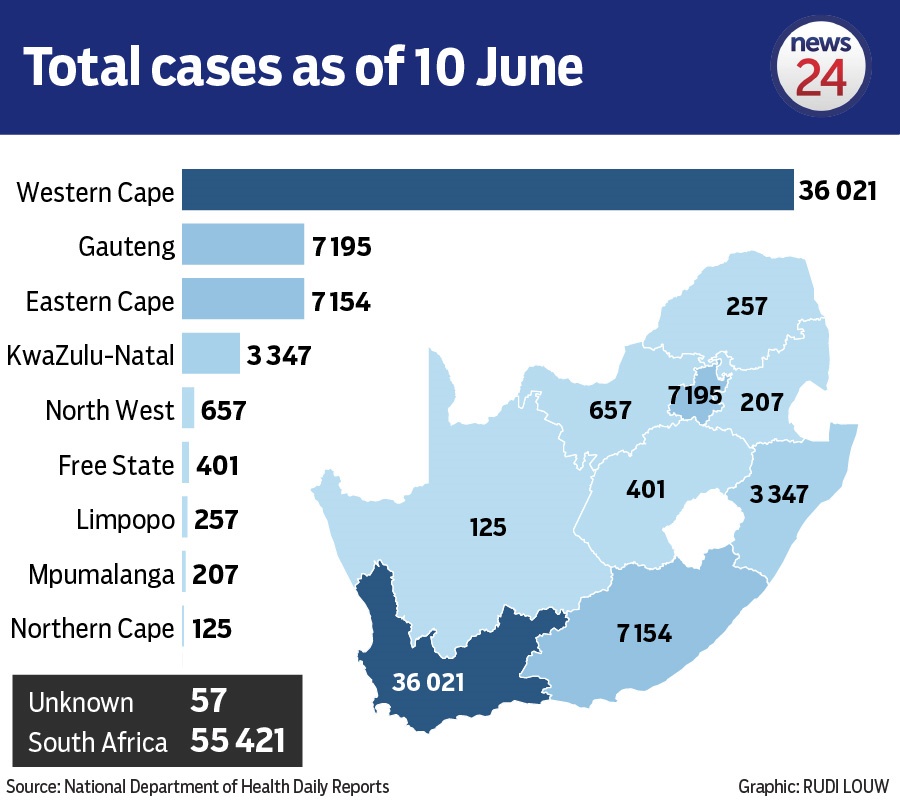

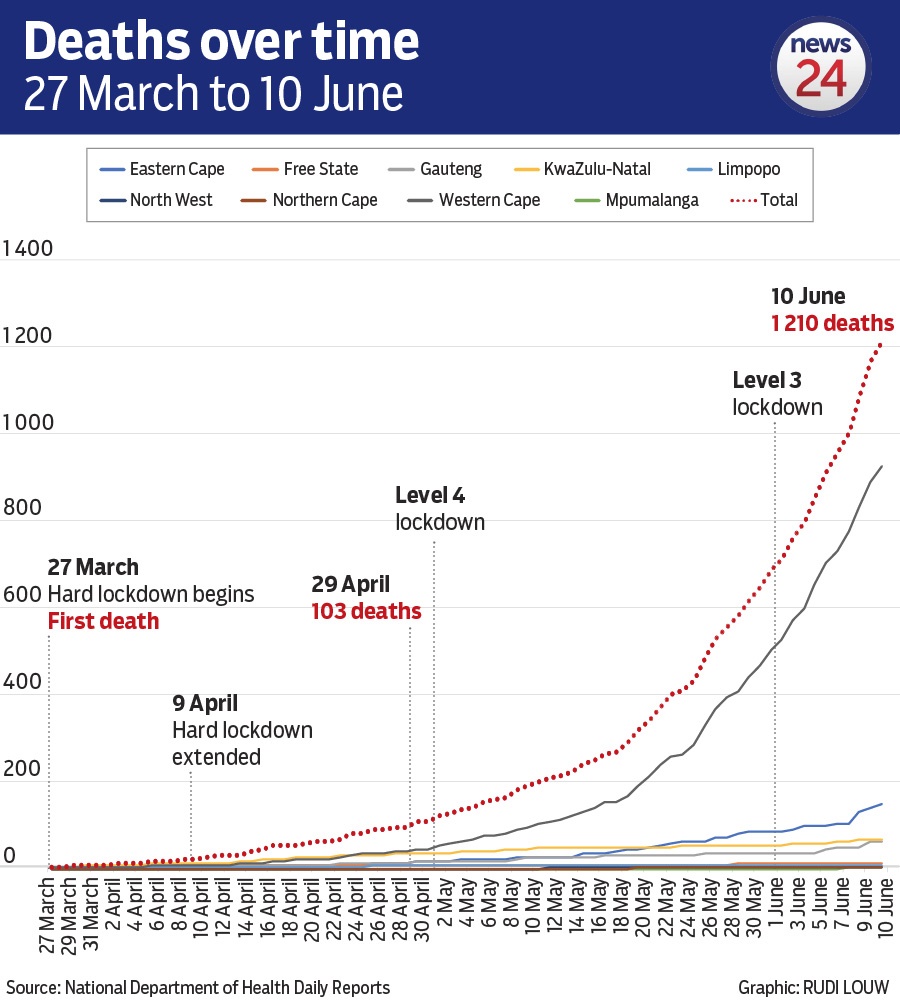

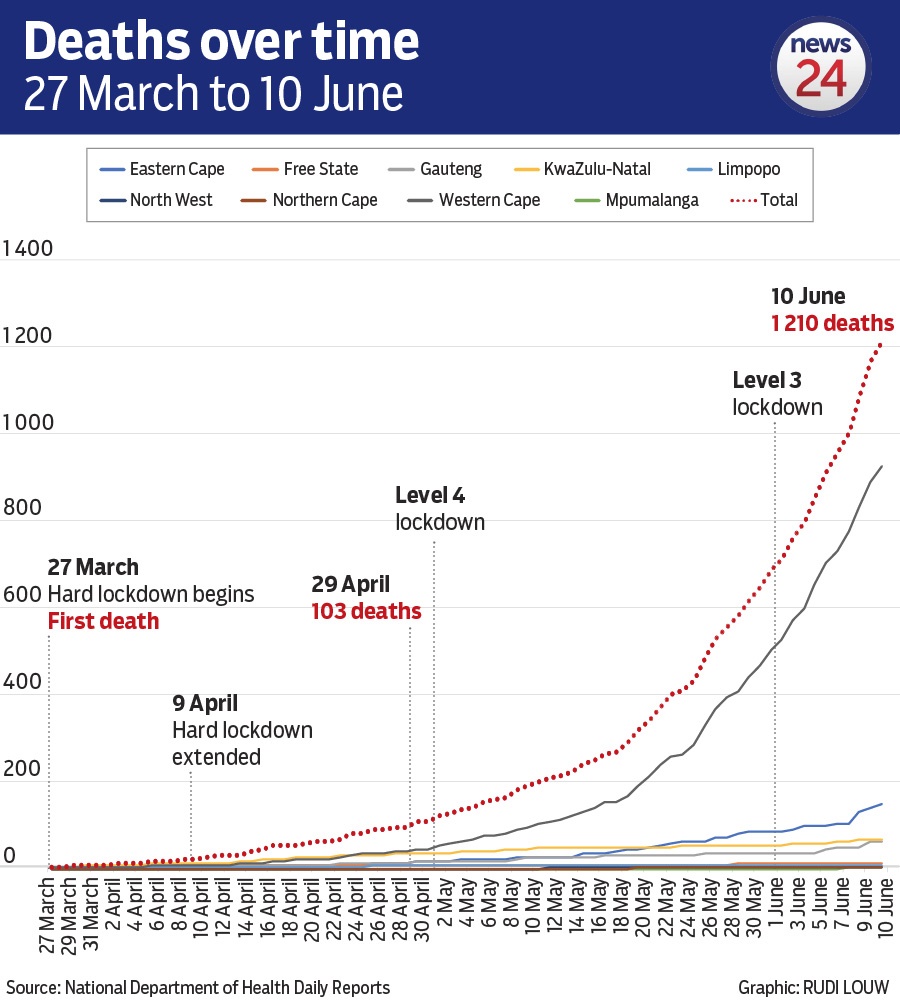

- Covid-19 has so far claimed 1 210 lives, and infected 55 421 as the economy buckles under lockdown pressure.

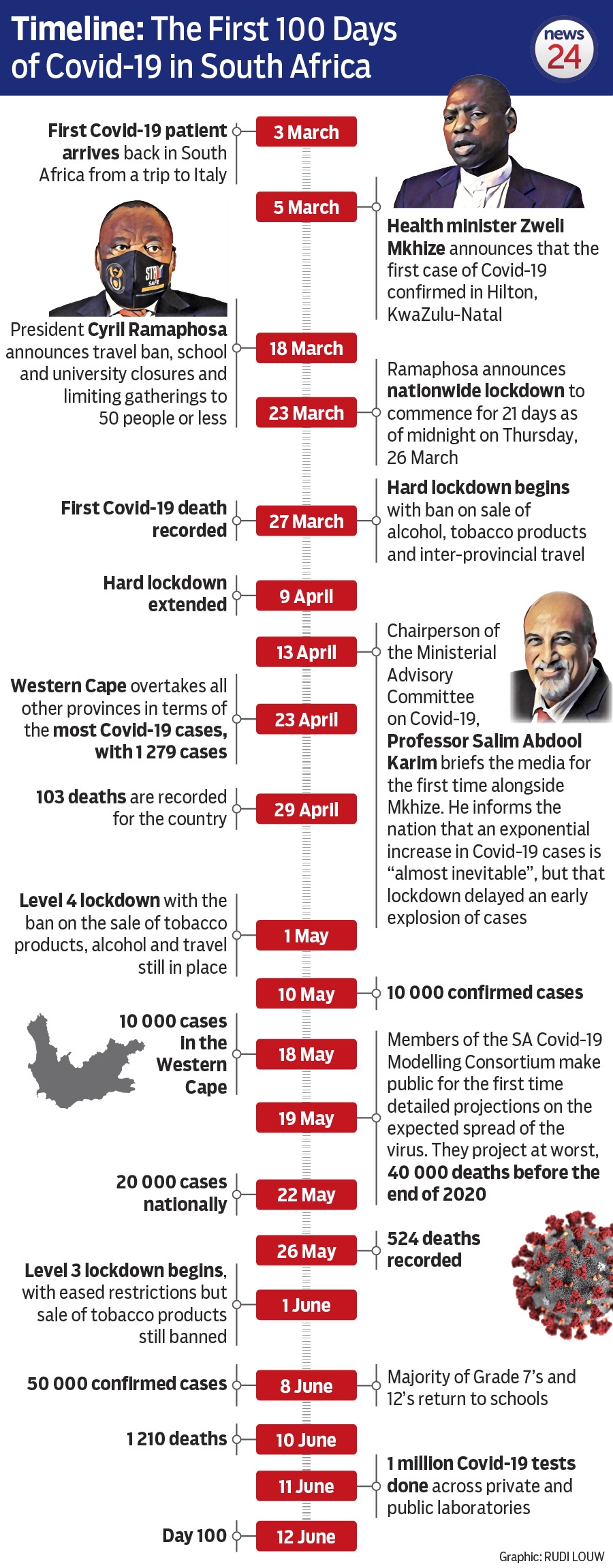

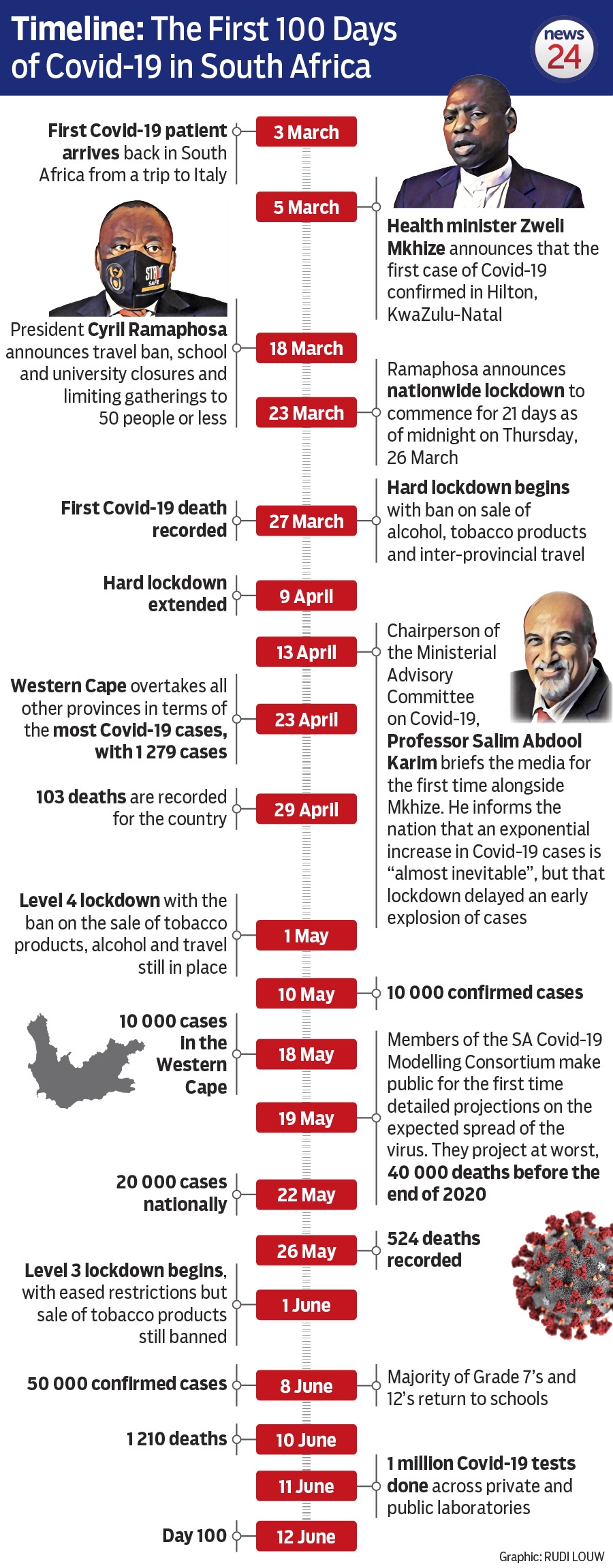

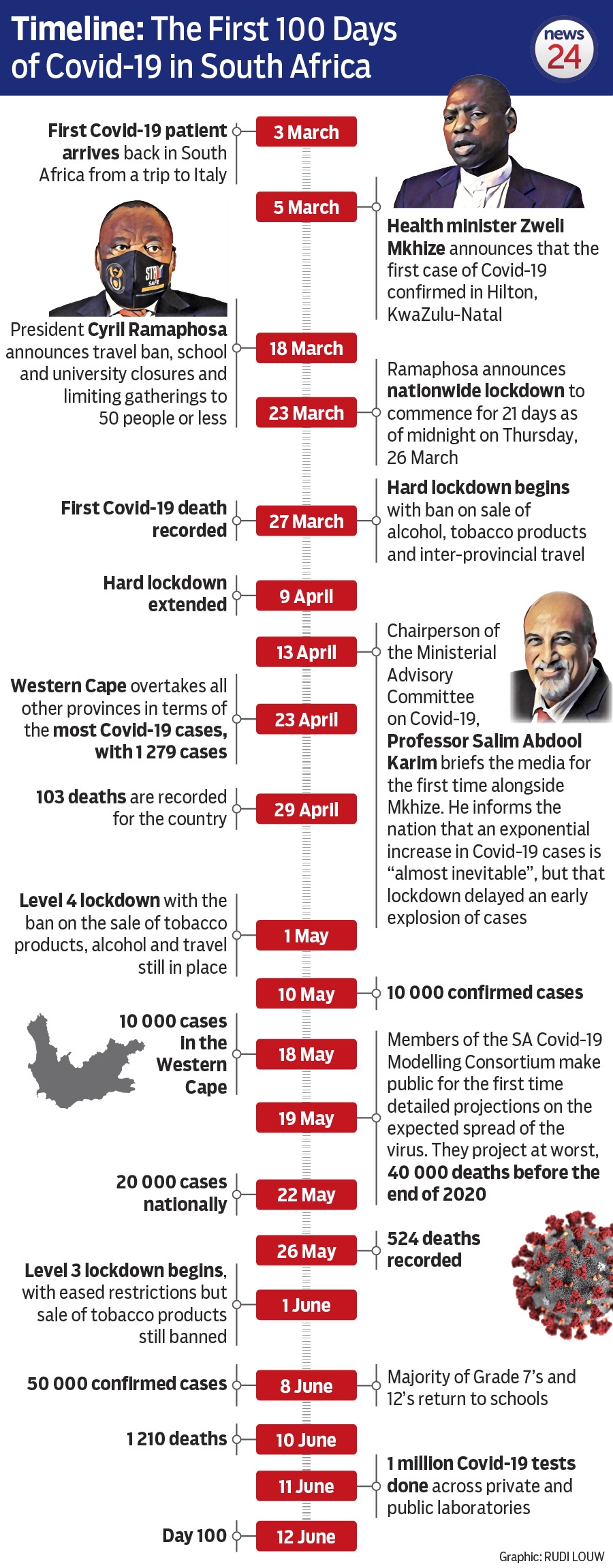

Friday marks exactly 100 days since the first person confirmed to have Covid-19 arrived back in the country from a holiday trip to Italy on 3 March.

Two days later, Health Minister Zweli Mkhize announced the man, from Hilton in KwaZulu-Natal, was the country’s first case.

In the 100 days since the man first felt ill and visited his doctor, the country’s response has been marked by a scramble to prevent the virus from spreading too far and too fast, a nationwide lockdown and emergency steps to alleviate hunger and job losses as the lockdown had an immediate impact on the economy.

Billions of rand have been poured into unemployment funds, social grants, water supply and food parcels and more billions have been spent on obtaining emergency medical supplies such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing equipment.

Gauteng Premier David Makhura said, optimistically, 890 000 jobs would be lost in the province alone, the economic hub of the country.

The South African economy was expected to lose R285 billion in tax revenue alone, according to SARS commissioner Edward Kieswetter, directly as a result of the lockdown implemented to curb the initial spread of Covid-19.

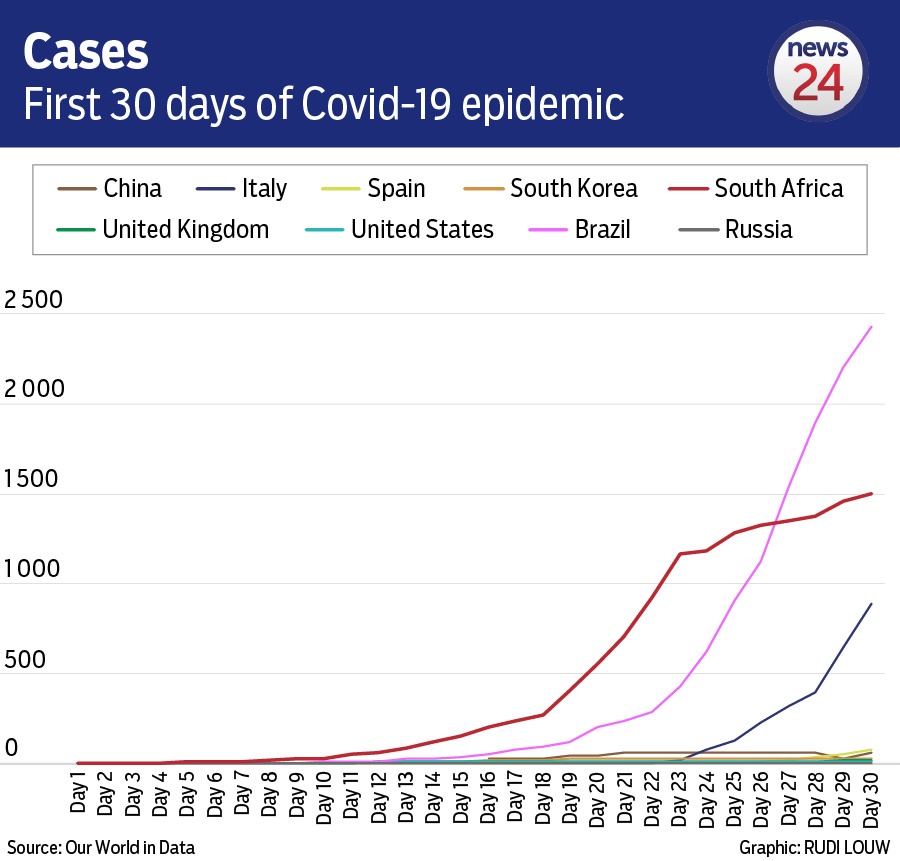

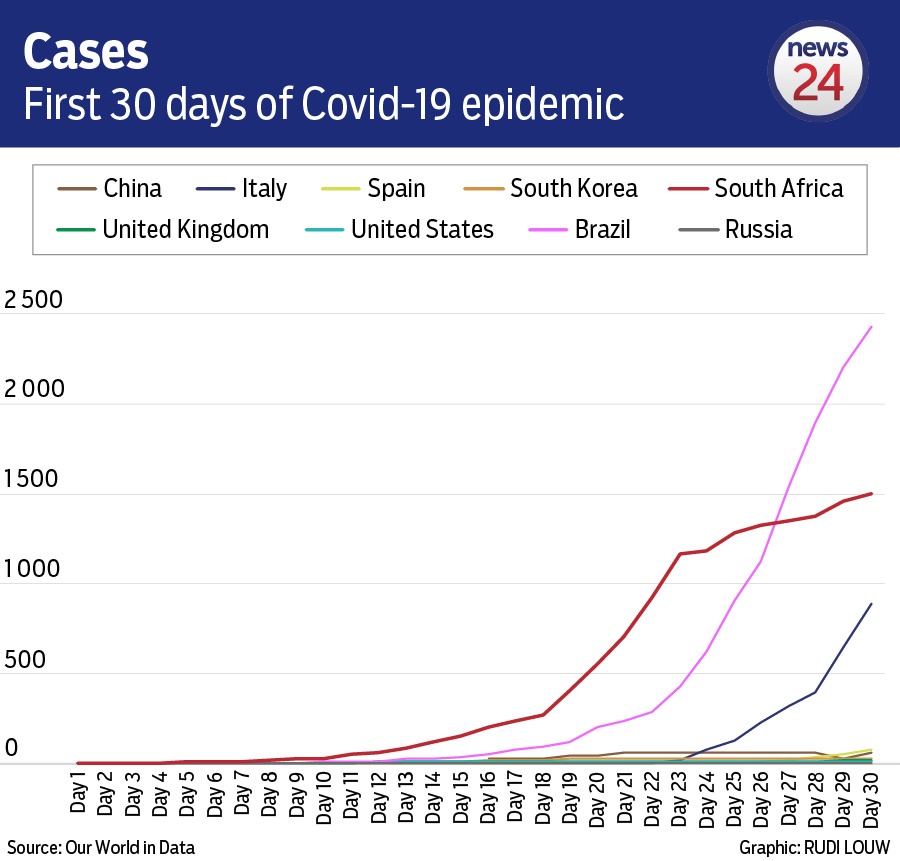

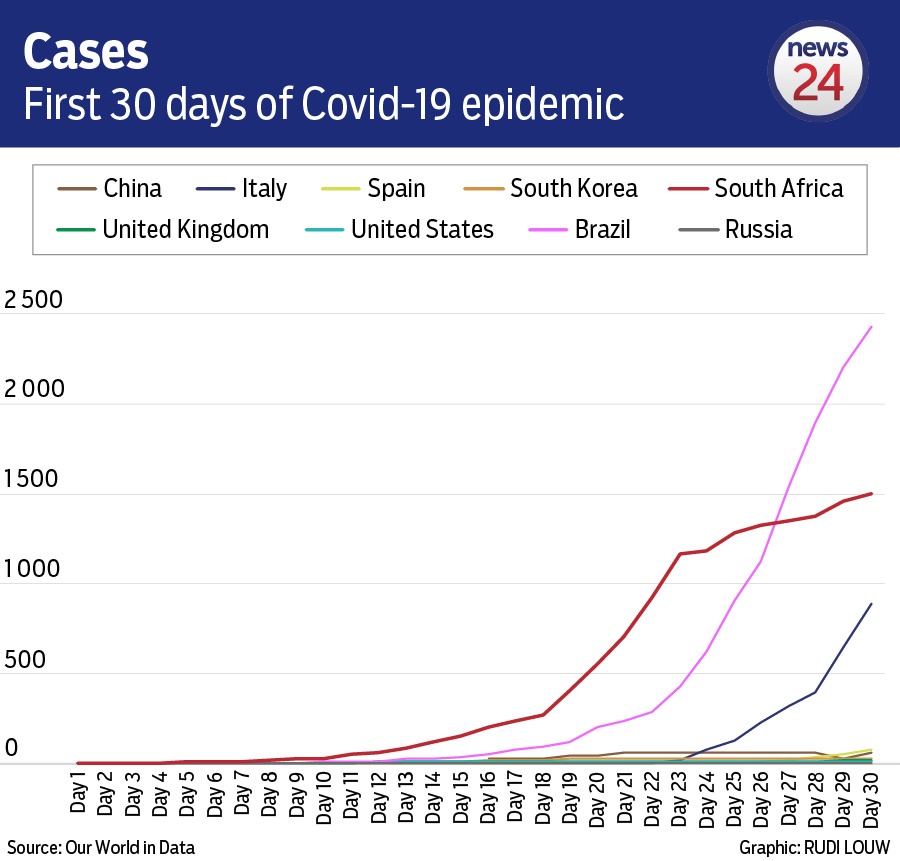

But, the measures helped the country halt the initial spread of the virus, especially in the first 30 days, where the travel ban had a marked effect, as seen in this comparison of the first 30 days of the epidemic in various countries.

This graphic compares the countries by day of epidemic, not date of case reported. Day 1 in South Africa is 5 March, compared to much earlier dates in January and February for the others.

The marked dip around Day 22 was, according to epidemiologists advising the government, the effect of the travel ban which halted the importation of cases, which accounted for the majority of the country’s infections in the early weeks.

A large swathe of tax revenue lost emanates from lost sin taxes due to a ban on the sale of tobacco products and alcohol – but the majority is a simply knock-on effect of drastically reduced economic activity.

Alcohol sales resumed as of 1 June, but already the effects of alcohol-induced accidents and violence has seen a sharp increase in trauma admissions at hospitals, sparking a call from Eastern Cape Premier Oscar Mabuyane to reinstate the ban on alcohol sales.

Some economic recovery was expected, according to analysts, but the damage has been done. Equally, the impact of Covid-19 on lives is starting to increase – by Thursday afternoon 1 284 lives had been lost, and 58 568 people confirmed to be infected.

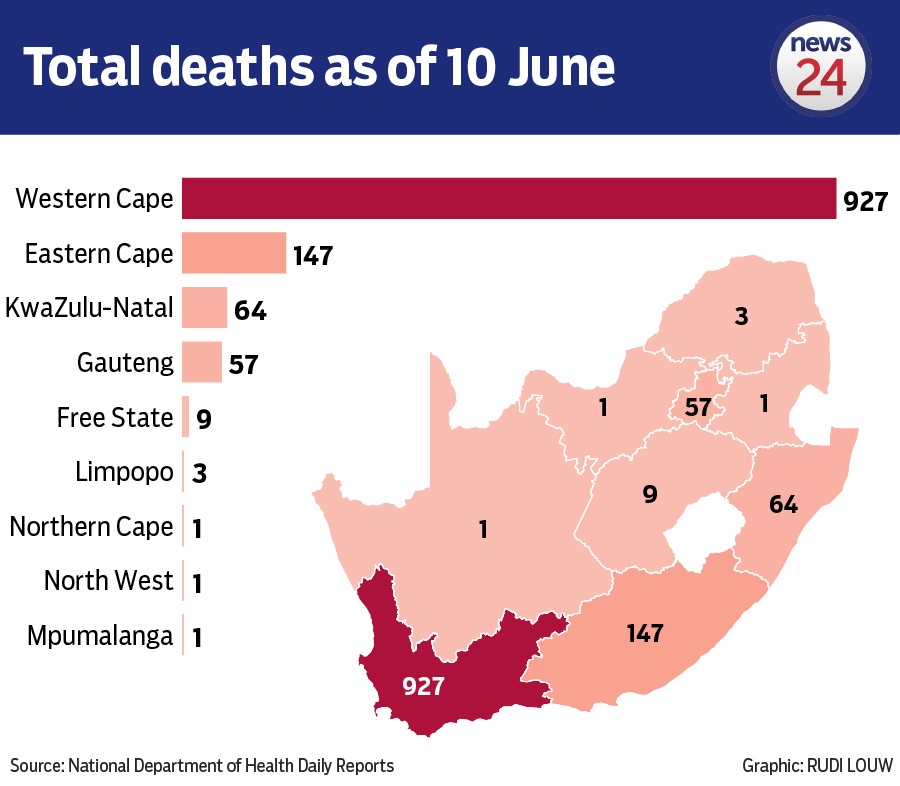

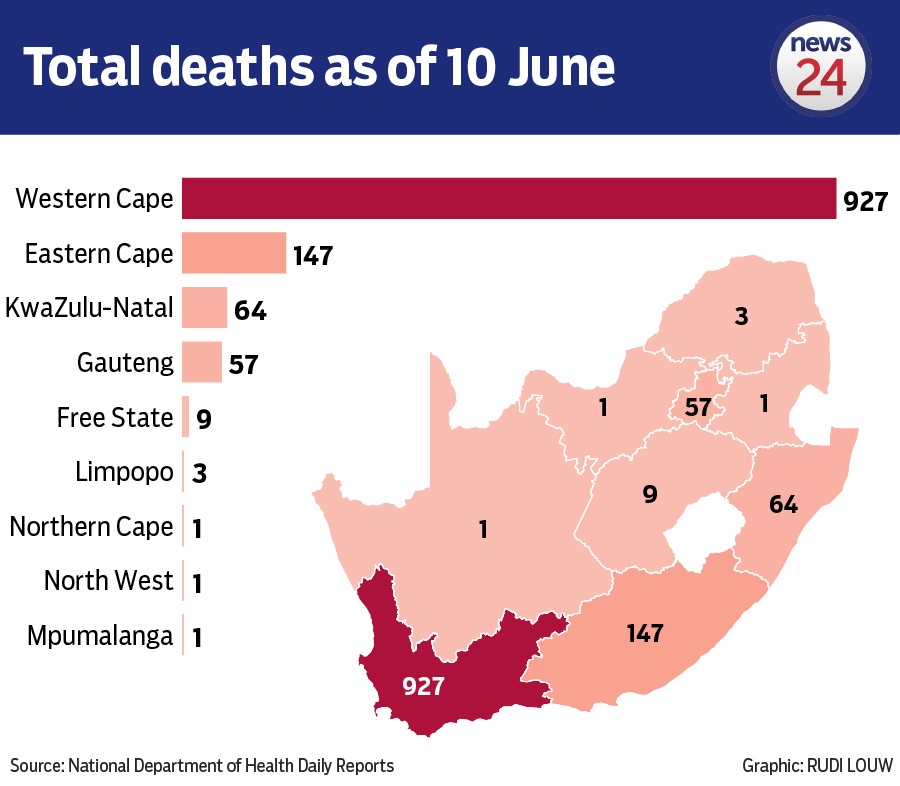

The national numbers are, however, heavily weighted by the Western Cape, which is experiencing the worst outbreak of any province. Infections and deaths account for roughly 75% of the country’s total cases.

According to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), every province was experiencing a rise in numbers of cases and deaths – but when viewed on a linear graph such as this, it is clear the Western Cape is the outlier.

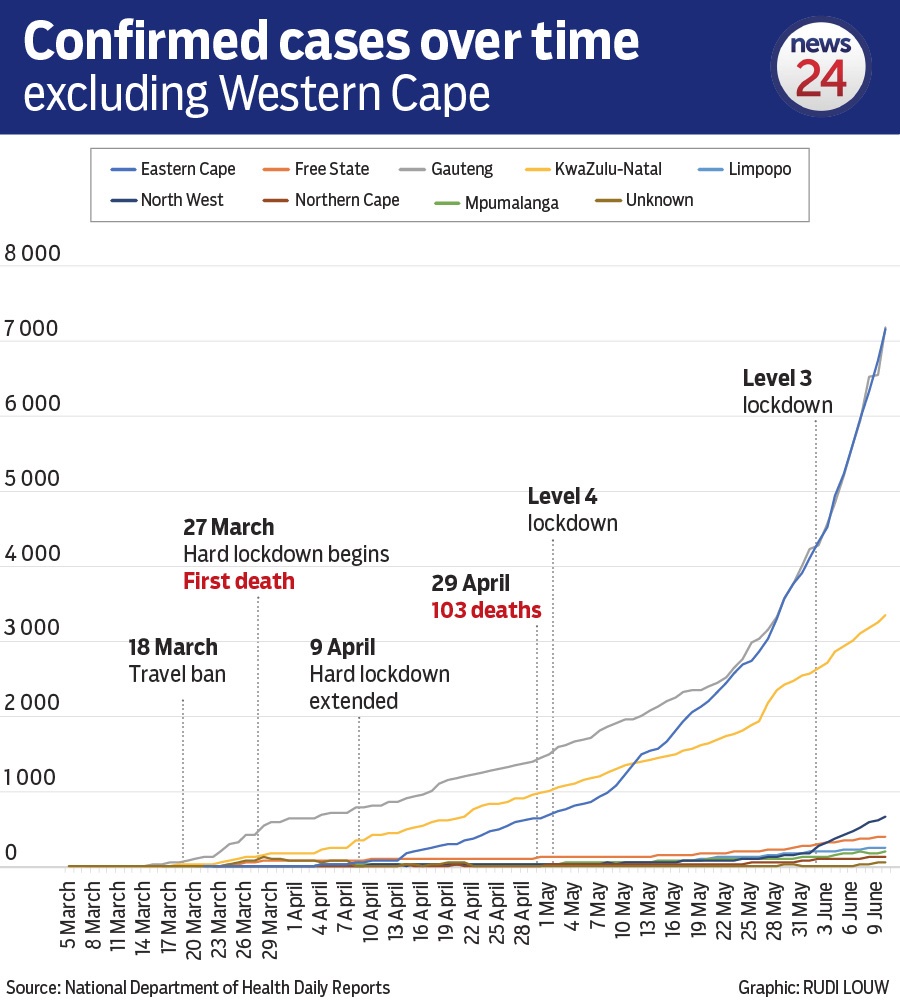

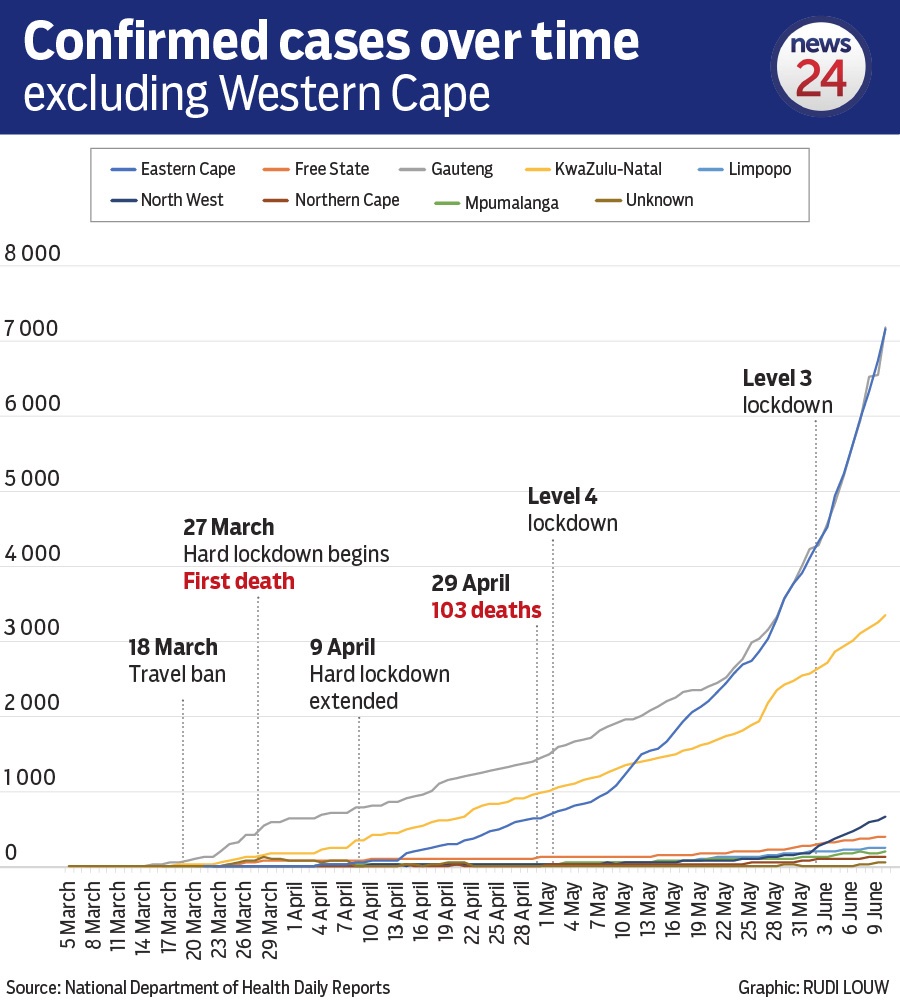

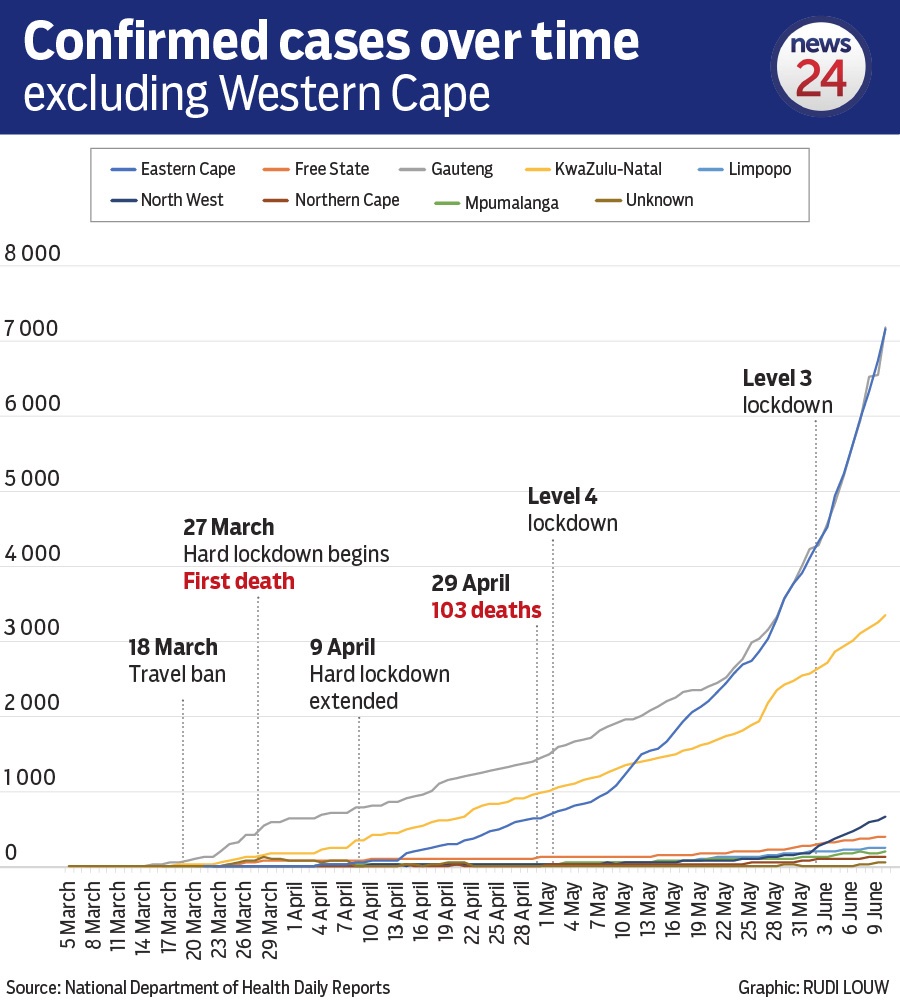

Without it, the overall picture is far more conservative.

This graph, while indicative of the cumulative cases in provinces over time, can be misleading – the Eastern Cape is experiencing a much faster outbreak than Gauteng, even if the provinces appear to be recording the exact same number of cases.

A closer look reveals it took Gauteng 93 days to reach 5 900 cases, while the Eastern Cape took only 79.

Similarly, as of Wednesday, the Eastern Cape had record 147 deaths, compared to 57 in Gauteng. By Thursday, deaths in the Eastern Cape had risen to 178.

The Western Cape has also recorded the largest number of deaths.

These graphs can make interpreting the growth of Covid-19 over time difficult due to the much higher number of cases in the Western Cape.

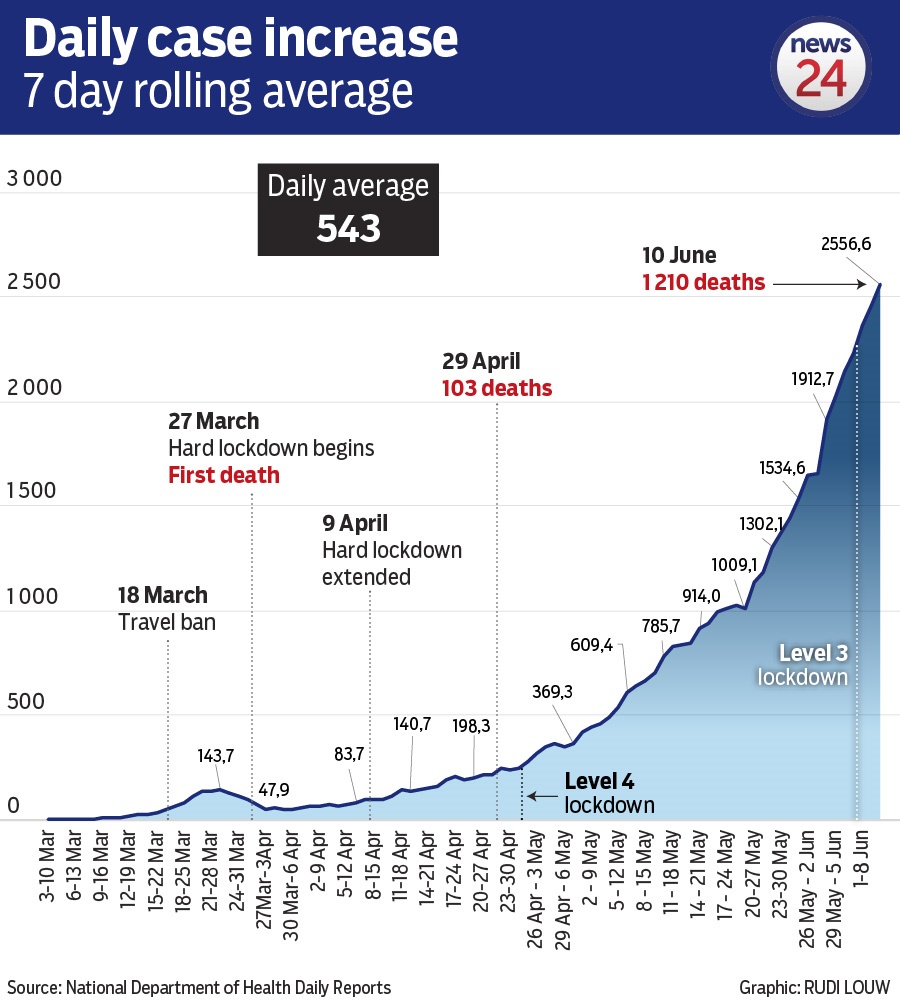

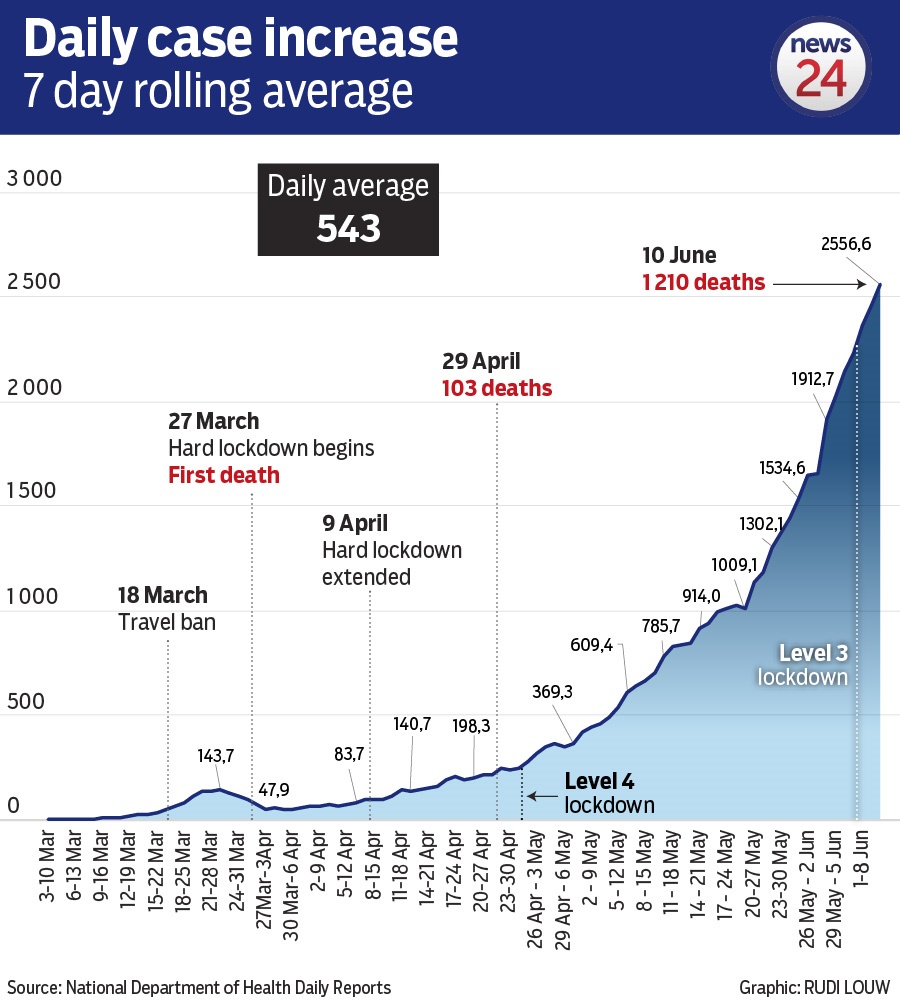

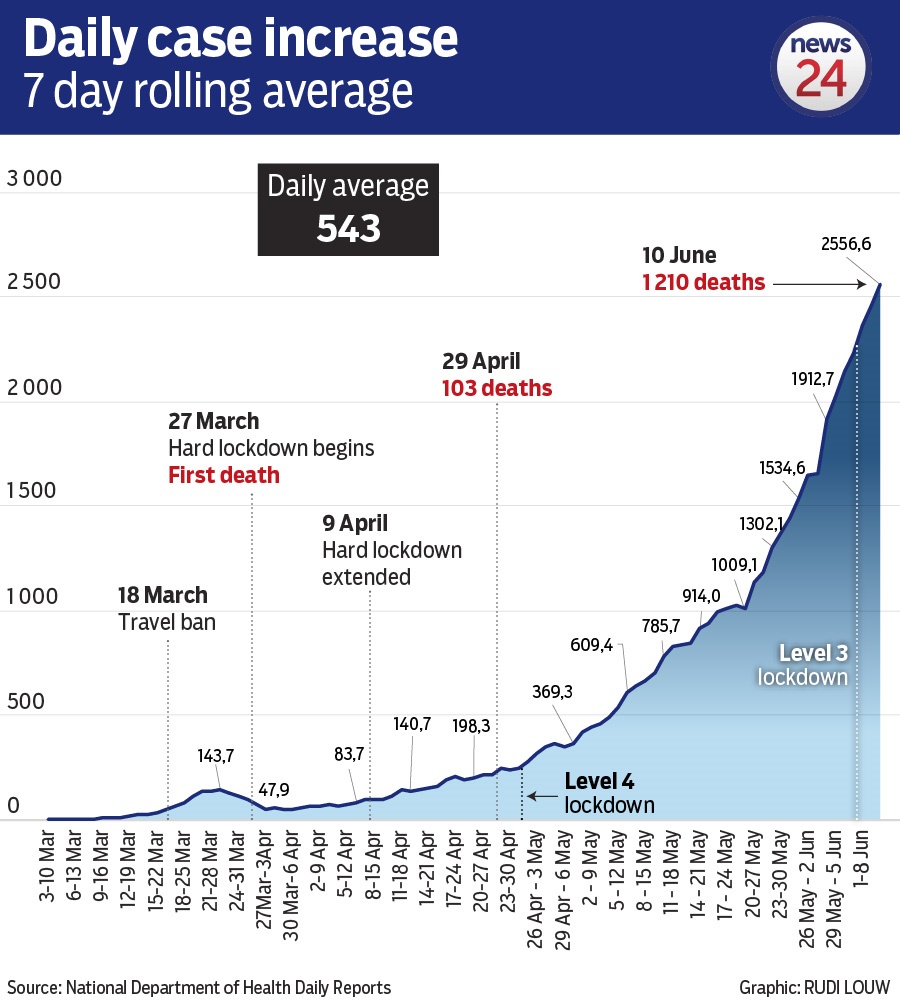

A better analysis is to look at the average daily increase in cases on a seven-day rolling scale.

For the week 3 to 10 June, the average daily increase in cases was 2 556.6, compared to 461 for the week of 3 to 10 May.

The overall average daily increase over time is 543 cases per day. But the finding of cases is directly linked to the number of tests and testing strategies.

Led by the Western Cape, it appears testing strategies are changing to focus on healthcare workers and patients already hospitalised. This is largely due to a backlog in tests which, as of 9 June, was a little more than 70 000 in public laboratories.

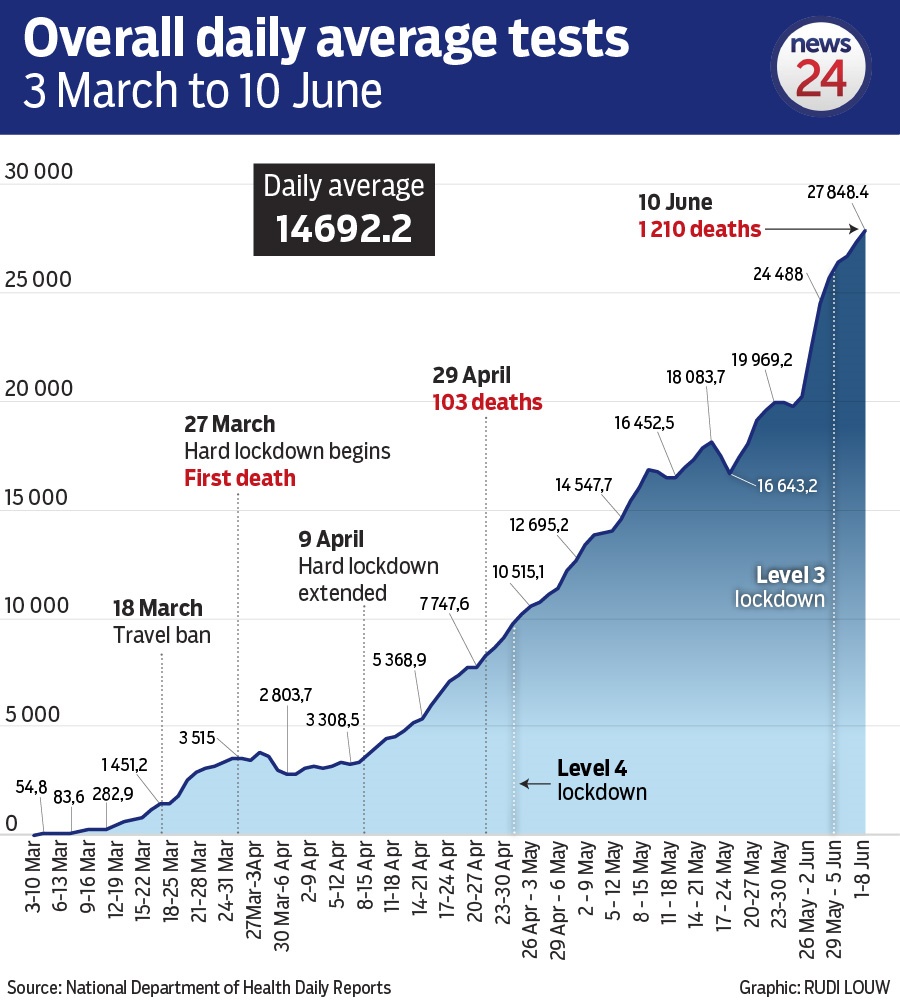

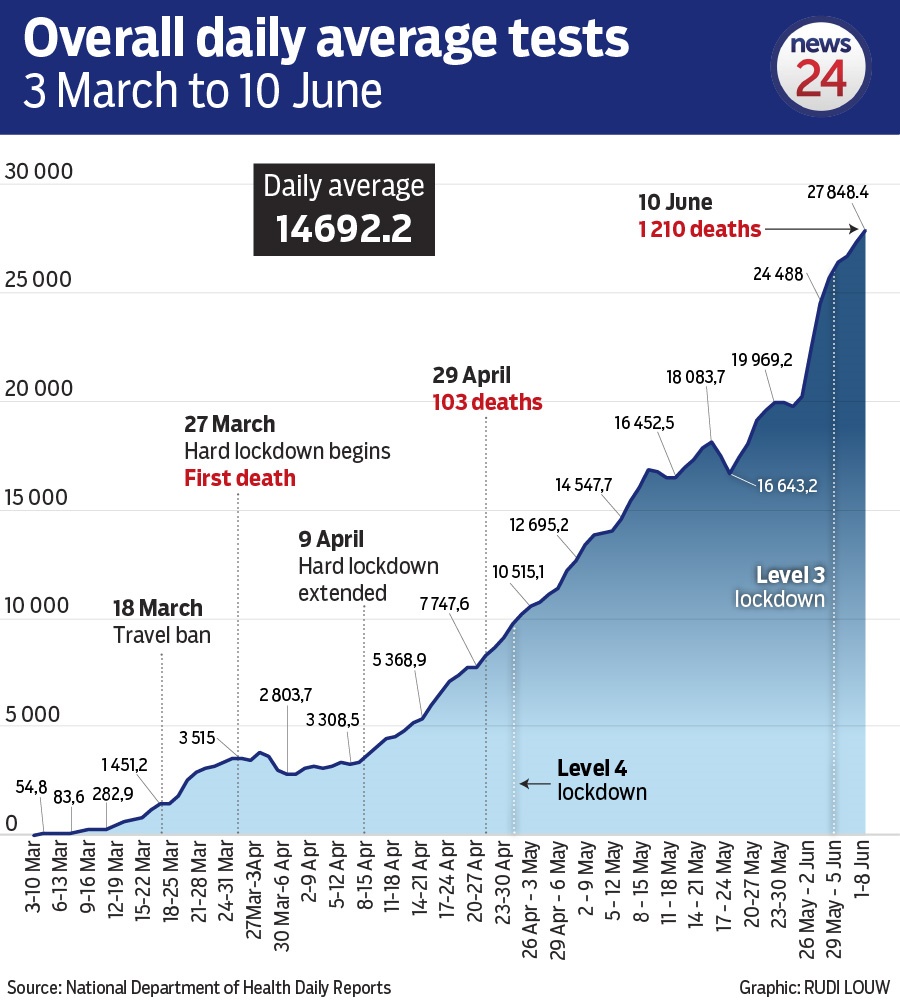

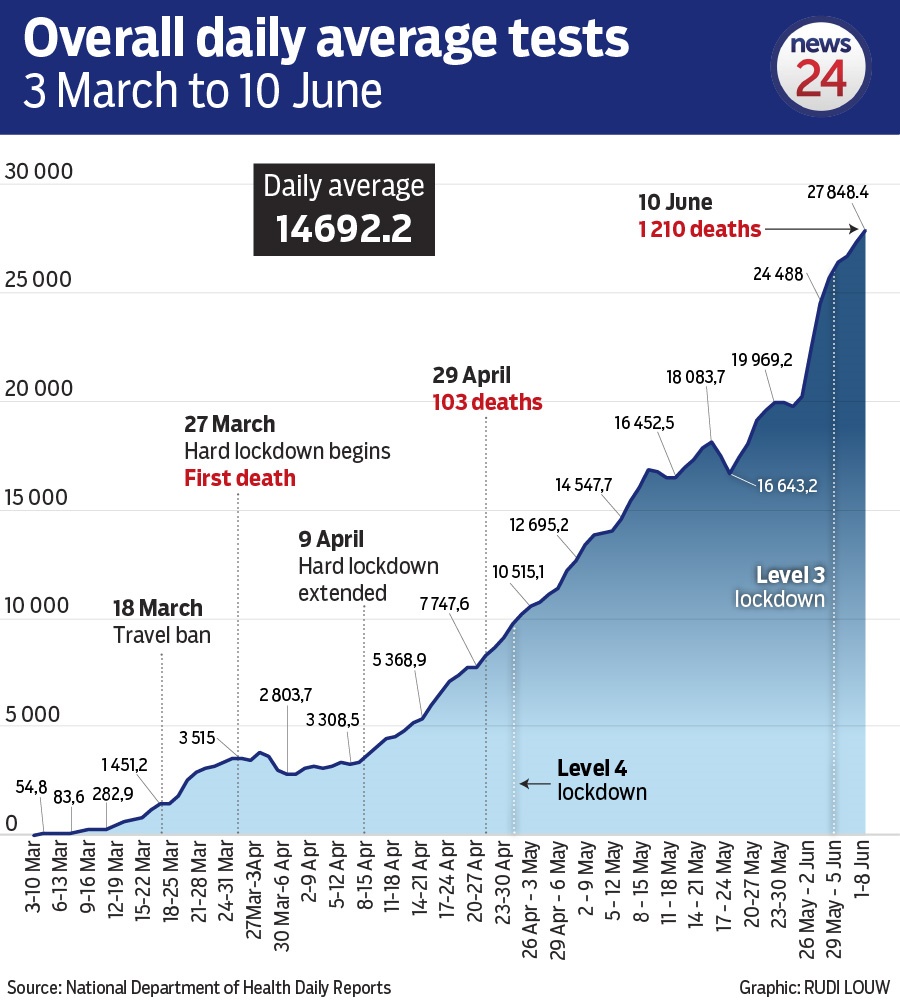

The overall average number of tests done between 3 March and 10 June in public and private laboratories is 14 692.2 per day. More than 1 million tests had been conducted in the country by Thursday afternoon.

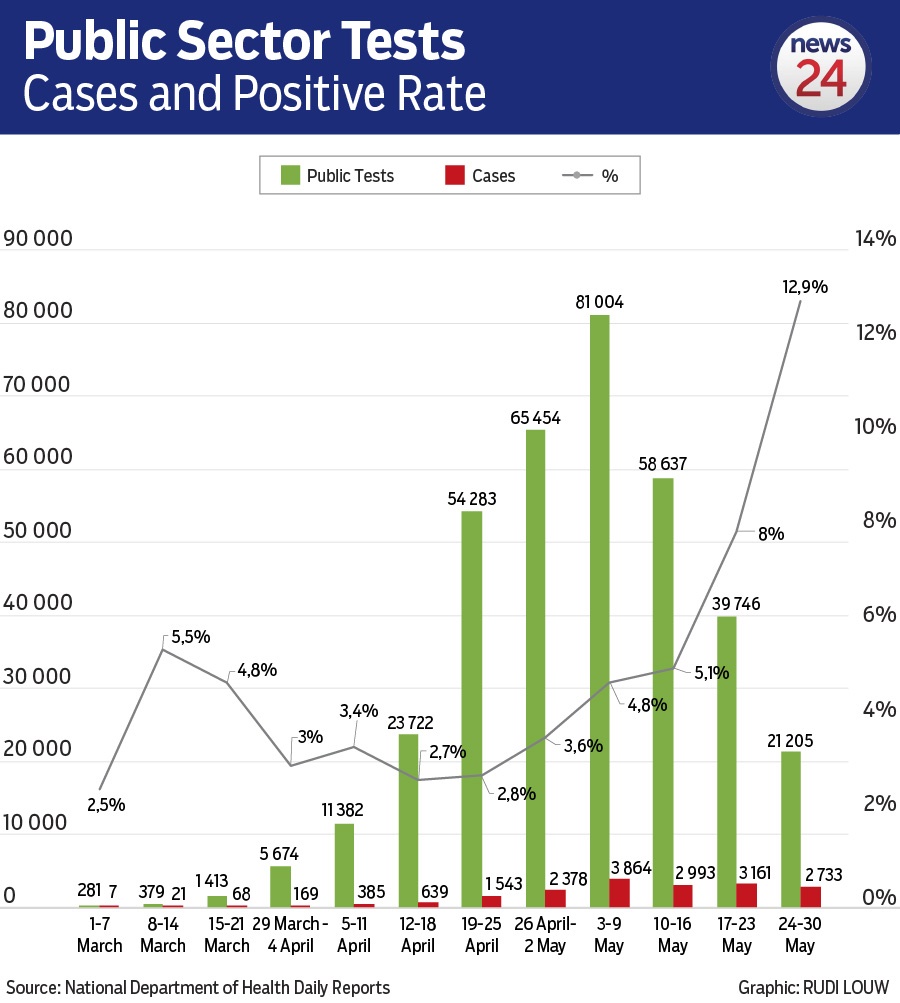

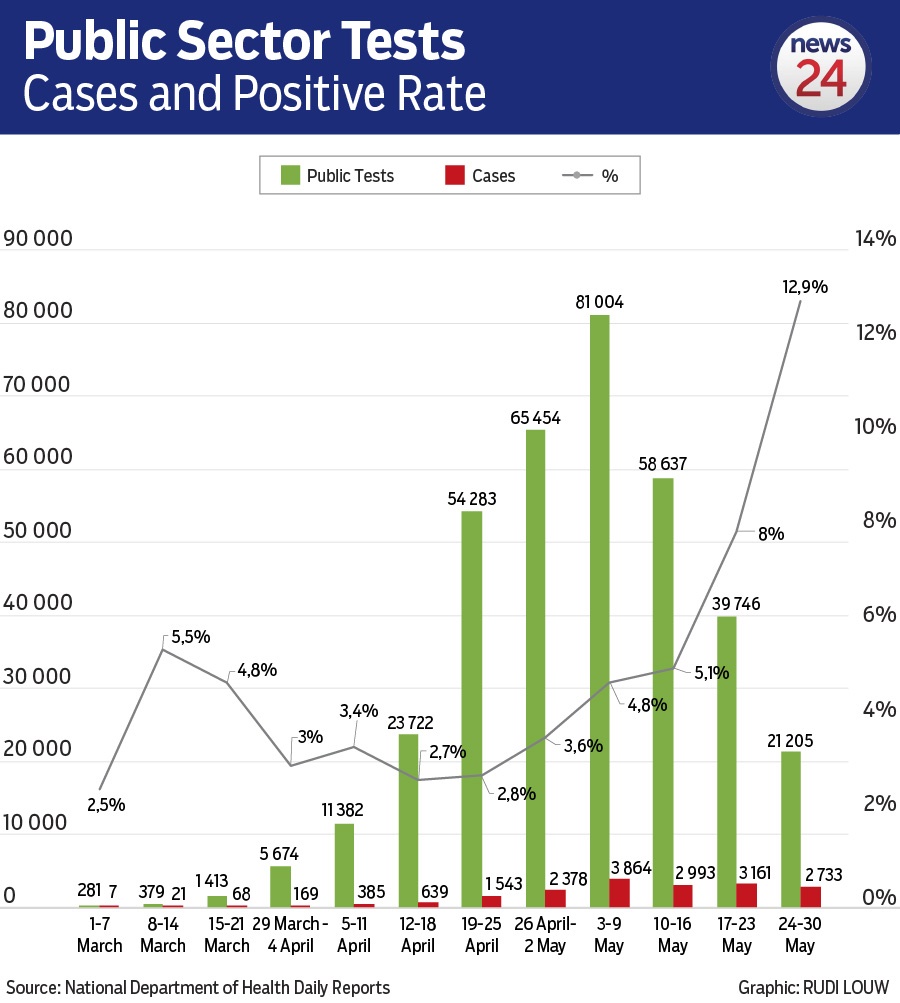

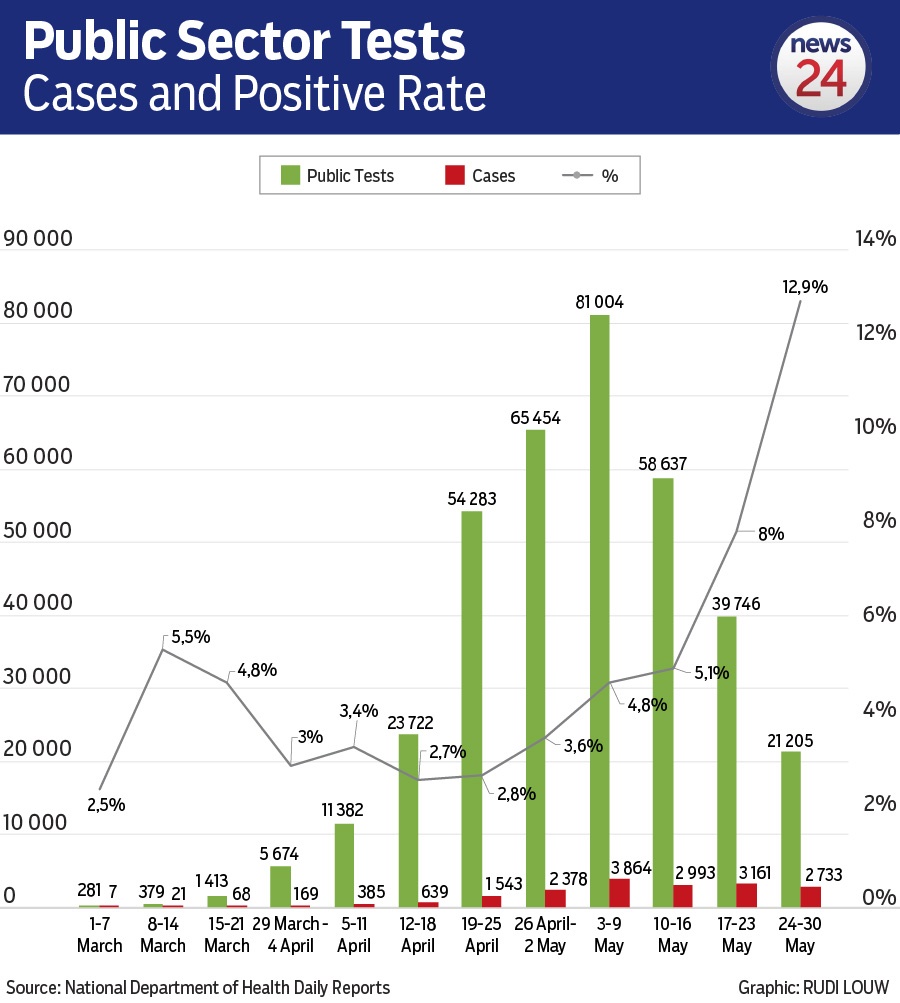

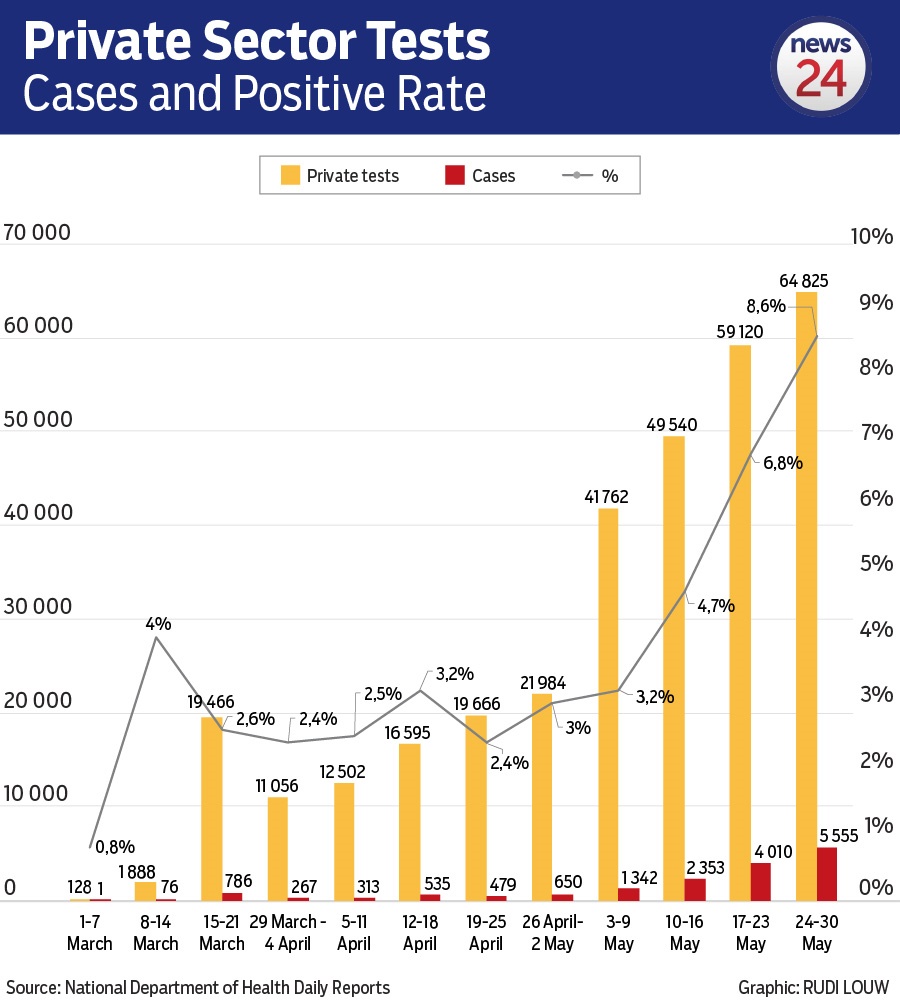

The change in testing strategies is clearly visible here in the higher percentage of people testing positive in the week between 24 and 30 May, which according to data published by the NICD was 12.9% in public laboratories, compared to 8% for the week of 17 to 23 May.

For the week of 1016 to May, 5.1% of people tested in public laboratories tested positive for Covid-19.

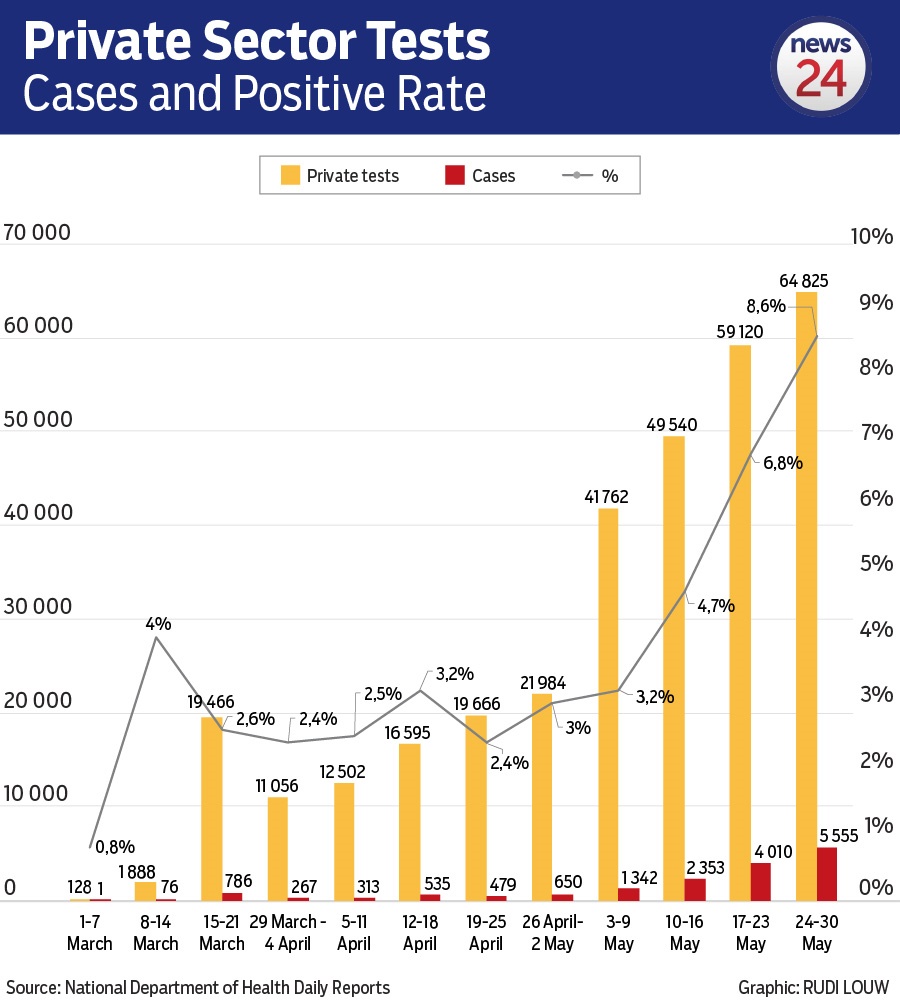

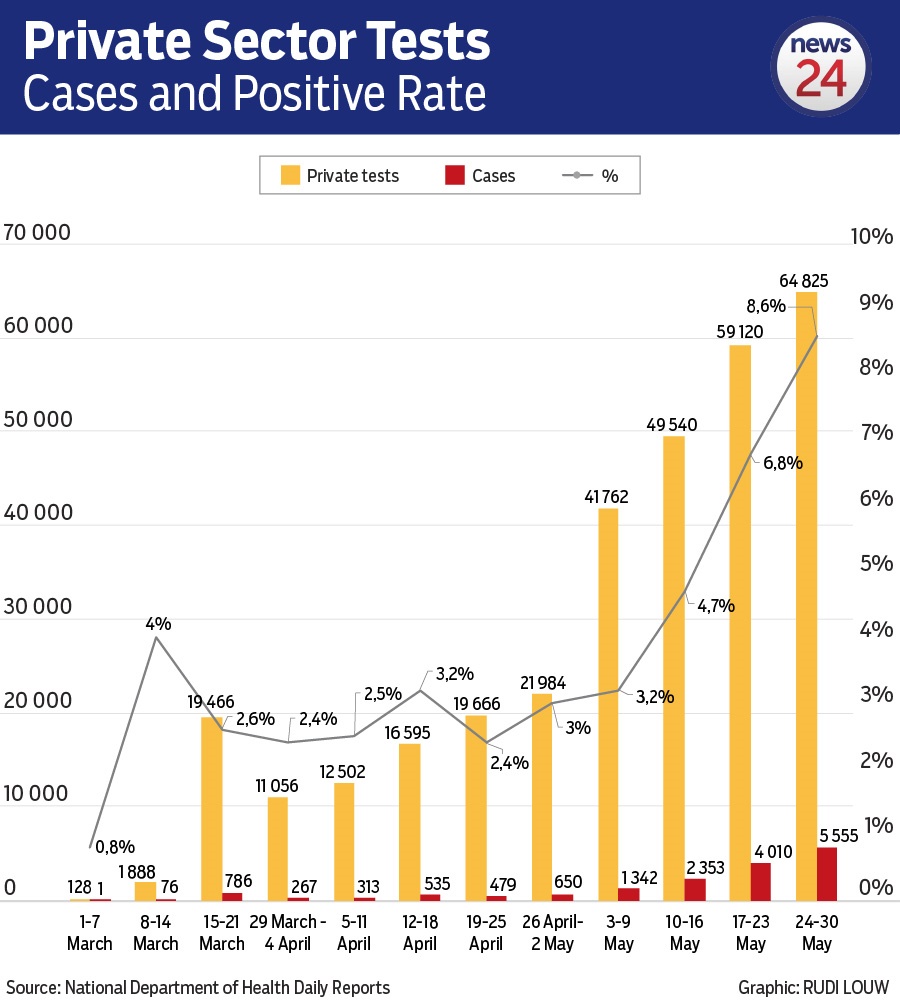

The increase in positive testing rates in private labs is also up, to 8% for the week of 24 to 30 May and has been rising steadily – most likely the effect of changes in testing strategies.

In contrast to this is, more people are being hospitalised and tested, because more people are falling ill from Covid-19.

In the coming weeks, a surge in cases Mkhize has long warned off, is likely to take place but only time will tell if the country’s health systems are prepared.