Money or your life? —

After limiting its lockdown, Sweden is neither success story nor disaster zone.

John Timmer

–

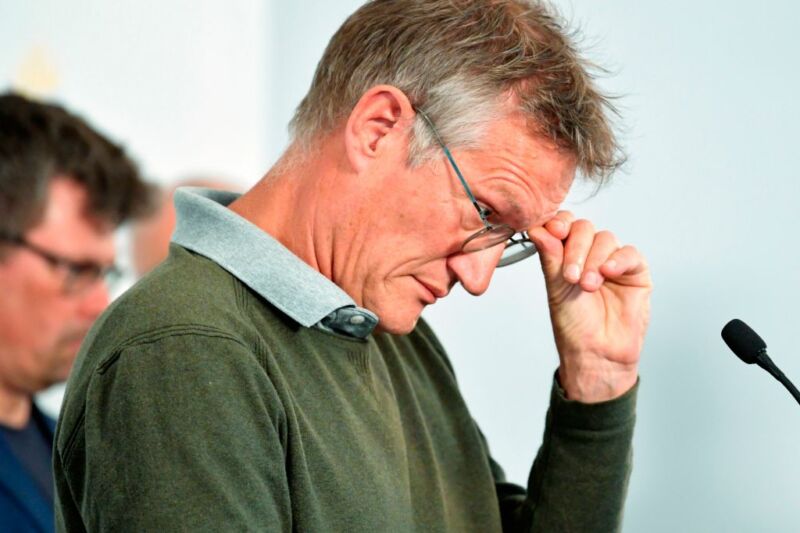

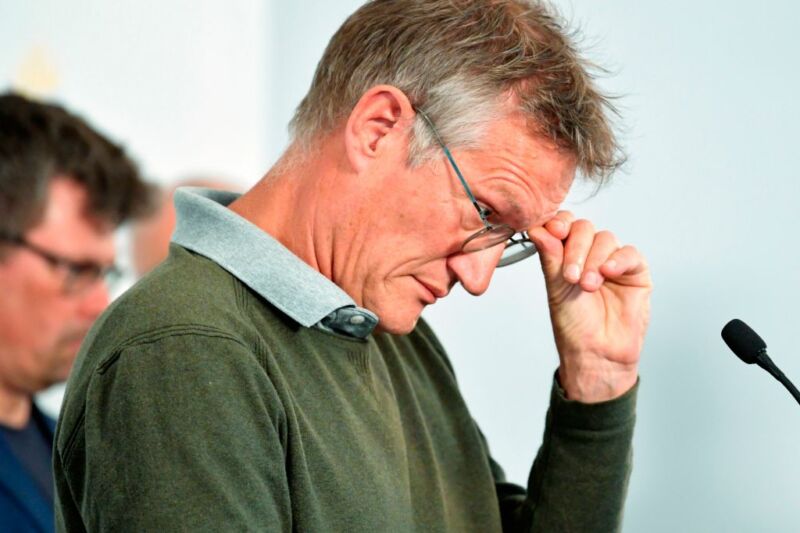

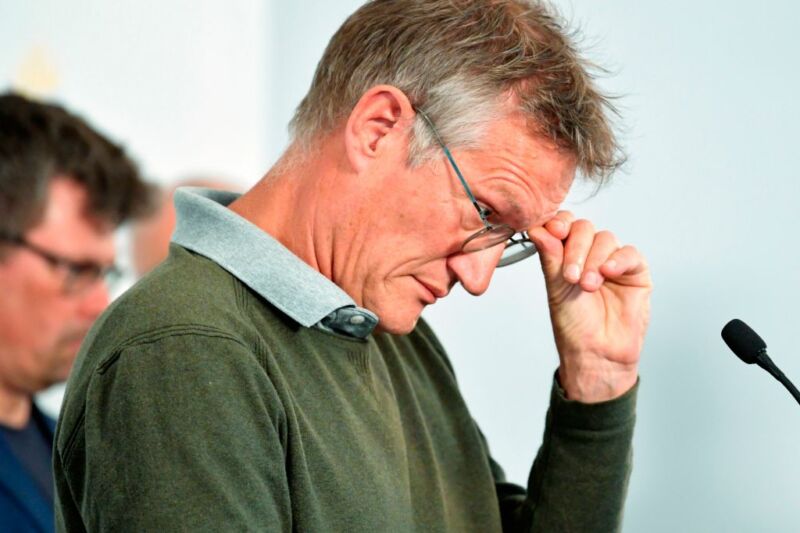

Enlarge / State epidemiologist Anders Tegnell of the Public Health Agency of Sweden has admitted that the pandemic response he promotes hasn’t worked out as well as he hoped.

ANDERS WIKLUND/Getty Images

Earlier this week, Sweden’s government epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, admitted that his plans for how the country should handle the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic hasn’t quite worked out as he hoped, saying there’s “quite obviously a potential for improvement in what we have done,” according to one translation. There are probably very few public health officials on the planet who couldn’t say the same. But Tegnell’s admission made headlines, largely because Sweden has charted its own path, starting with relatively light restrictions compared to other European countries in the hope that the pandemic’s economic impact would be blunted.

That approach has turned Sweden into a political talking point far from the Baltic Sea, with many people who would be horrified by Sweden’s taxation levels and social safety net suddenly adopting it as a model of minimal government intervention. The role of Sweden in Internet arguments grew increasingly large as opposition to social distancing measures became organized in a number of countries. So, with the country’s coronavirus plan architect saying mistakes were made, it’s worth taking a look at how Sweden handled the pandemic—and what the results have been.

The plan and its economics

Some countries in Europe, like Italy and Spain, were faced with a rapid surge in cases early in the pandemic; others had the examples of Italy and Spain to guide their policy. The end result was that most European countries imposed pretty severe social distancing regulations, banning large gatherings, closing schools, and limiting access to a variety of businesses. In most cases, this has limited the spread of the pandemic, or at least it started to bring an out-of-control situation back into something more manageable.

Sweden largely didn’t do this. Restaurants and cafes remained open, as did the lower grades in schools. Sporting events did stop, and people were asked to protect the most vulnerable and elderly populations. But many of those measures were voluntary. Personal protection, like face masks, weren’t encouraged for general use.

The hope was that, by protecting the vulnerable populations, the impact of the disease itself would be minimal, as would the impact of the restrictions on most sections of the economy. (Professional sports teams were, presumably, going to have a hard time due to the rules.)

Is that working? Maybe? Early results looked good, as economic data from the first quarter of 2020 showed Sweden’s economy grew; the anemic growth (0.1 percent) was still far better than most other countries could manage. And, more recently, the country’s chief economist indicated that the expectation is that the year would see the economy contract by roughly seven percent amidst heavy borrowing and record job losses. That’s somewhat better than Europe as a whole, where the EU is expecting an 8.7 percent contraction, but it’s not dramatically better.

Anecdotal reports suggest the businesses that have remained open aren’t seeing many customers, and the overall economy is heavily reliant on exports, which have slowed dramatically. So, even if its policy had allowed it to escape the worst of the pandemic, the country couldn’t fully escape the pain of its trading partners.

The human cost

But it’s very clear that Sweden hasn’t escaped the worst of the pandemic, or its epidemiologist wouldn’t be questioning its plan. The news that specifically prompted his re-evaluation is the country’s high death rate, but there are a number of measures by which Sweden isn’t doing especially well. Using information from Our World in Data, we’ve looked at how the pandemic has progressed in Sweden.

(Unfortunately, for reasons that aren’t clear, Sweden seems to have seen a large spike in cases in the most recent weeks. This is likely due to a change in reporting methodology; it’s more useful to focus on the trends prior to this spike, as we will here.)

We’ll start by looking at the cumulative confirmed deaths per capita, a measure where changes will provide an indication of how effective control efforts have been. For Spain, a country that had a severe early outbreak, deaths per capita rose dramatically, but they have now tailed off due to extensive control measures. In the US and UK, where control measures came late and, in the latter case, have been half-hearted, the rate of death is only tailing off very slowly. For Sweden, the trajectory looks much like it does in the US and UK, as you’d expect based on the lax controls.

-

Sweden’s confirmed cases per capita are similar to some very badly hit nations.

Our World in Data -

Sweden isn’t as bad off as the UK, but hasn’t seen cases tail off, as Spain has.

Our World in Data

In fact, if you look at the weekly change in confirmed cases per capita, it’s clear that (even excluding the recent spike), Sweden was doing no better than the US and UK.

The contrast is far more dramatic if you compare Sweden to its most relevant neighbors, the other Scandinavian countries. Denmark, Finland, and Norway have all seen a spike in cases in late March/early April, but these countries quickly watched those increases fade after the imposition of significant social distancing policies. At this point, these countries are seeing very few new cases diagnosed most weeks. Sweden, in contrast, has seen its rate stay roughly constant throughout April and May—and it’s now seeing about 10 times the number of new cases as its neighbors. Deaths show a very similar story.

-

Unlike its neighbors, Sweden hasn’t seen a decline in new cases.

Our World in Data -

While other Scandinavian countries have seen COVID-19 deaths trail off, they remain high in Sweden.

Our World in Data

These numbers paint a clear picture: Sweden’s attempt to protect its most vulnerable hasn’t been very successful. In terms of its disease burden and death rate, the country is paying a far higher price than its neighbors. Those statistics are likely to be contributing to the suppression of domestic economic activity, as people are less likely to fully engage in an economy while being fed a steady stream of news about the pandemic’s impact on Swedish health.

And while Sweden’s economy may not suffer as bad as that of some other European countries, its heavy integration into the world economy has greatly reduced its ability to avoid the global damage the pandemic has caused.

Put differently, many public health experts and economists warned that we didn’t really face a binary choice between public health and the economy. Whatever other lessons will ultimately be drawn from the Swedish experience, it has strongly demonstrated that the experts were right.