Glenda Johnson sat on her mother’s hospital bed, took her hand and told her it was OK to go.

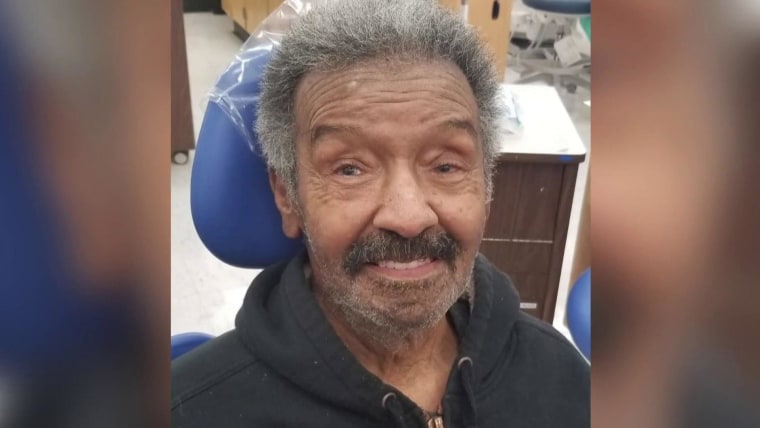

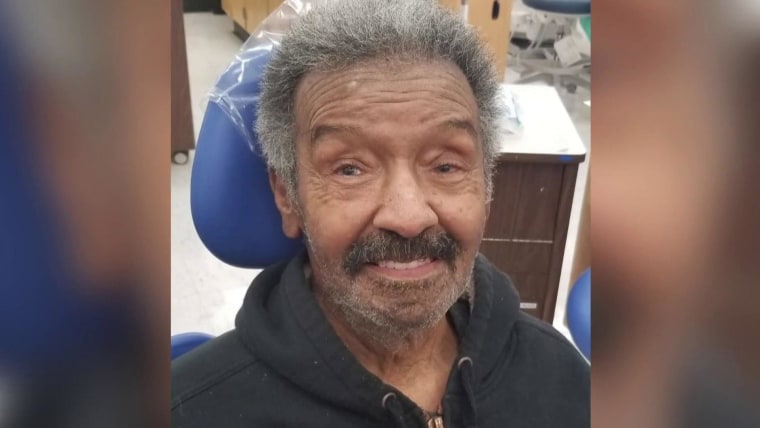

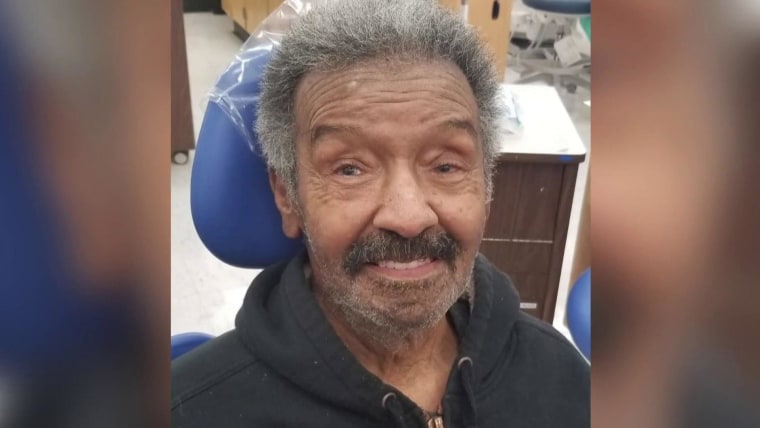

But Linda Hopkins, her face tensed against the smothering pain of coronavirus-related pneumonia, was not ready.

“I don’t want to die,” Linda, 83, replied, tubes feeding oxygen into her nostrils, her daughter later recalled. “It just hurts so bad.”

The two of them had a wonderful life in Detroit, about as close as a mother and daughter could be. They lived together, traveled together, shopped together, worshipped together, partied together. When they both fell ill in late March, they drove together to Beaumont Hospital in nearby Royal Oak, where they tested positive for COVID-19. They ended up in the same room, where they battled the disease together. Glenda, Linda’s only child, watched over her mother’s final moments.

“I have no husband, no kids, no brother and sister. My mother was all I had in the world,” Glenda said in a recent interview. “Now my heart is broken.”

Glenda, 58, a retired social worker, had been Linda’s caregiver since 2014. That was the year Glenda’s father, Clyde, died; her parents had been married for 57 years. Glenda quit her job, left her condo in the suburbs and moved back into the four-bedroom house in Detroit’s Bagley neighborhood where she was raised.

Linda, who had been head of acquisition and receiving at the University of Detroit Mercy, and Clyde, a former director of engineering for the city of Detroit, had traveled the world together. When he died, Glenda took his place on trips to Hawaii, Hilton Head, South Carolina, Washington, D.C., Chicago. In late February, as the coronavirus was just starting to spread through the United States, they canceled a visit to Las Vegas and instead spent the night at the MotorCity Casino in Detroit, where they gambled and ordered room service.

Both of them had busy worlds beyond their singular relationship; Linda belonged to the Red Hat Society and several card-playing groups and was active in her church and local library, and Glenda worked as an event planner. They cut back on their social activity in early March, but Glenda got sick later that month, and Linda followed about a week after, Glenda said. They first thought they had the flu, but grew concerned as their symptoms worsened. After Linda’s fever spiked on March 28, they decided to go to the hospital.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Just getting out of the house was an ordeal, both women stopping to catch their breath every few minutes as they dressed and packed, Glenda recalled. They drove slowly, in a caravan that included a cousin and a neighbor, to Beaumont, where, after waiting in the emergency department for a few hours, they tested positive for the coronavirus.

Glenda asked a doctor if her mother was going to die. “And of course they didn’t know, because they didn’t know anything about the virus,” she recalled.

Diagnosed with pneumonia, they were put in rooms on different floors of Beaumont, and spoke by phone multiple times each day. Glenda pressed her mother’s doctors and nurses for updates on her condition, and to make sure she was getting enough attention. On their fifth day in Beaumont, without their asking, Glenda and Linda were moved to the same room, a decision that Glenda said has made her grateful to the hospital. They talked, watched movies together, and called friends.

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

Glenda slowly improved, but Linda, who had diabetes, kidney disease and arthritis, deteriorated. She was put on dialysis. Her breathing grew more labored. Glenda tried to make her mother comfortable, helping her eat and adjusting her oxygen mask when it slipped off her mouth.

At one point, the doctors told Glenda that she had progressed enough to be discharged and go home, she said. But she still felt weak and short of breath. She’d also heard stories about families of coronavirus victims who were unable to see their loved ones in the hospital and had to instead speak to them by phone or video; many died alone.

Glenda said she refused to leave, telling hospital staff that she felt her health remained in jeopardy and she feared she’d never see her mother again. She said she asked whether the hospital planned to put someone else in her mother’s room, and the staff said no. The hospital allowed Glenda to stay, and continued to treat her.

“I wondered about the bill, but I said I could care less,” Glenda recalled.

Beaumont Hospital said it could not immediately comment on Glenda’s case, citing privacy rules.

On April 10, Linda seemed to rebound. She ate well and phoned friends, telling them she’d see them soon, Glenda said. But two days later, a Sunday afternoon, her pneumonia worsened, and she was unable to focus on much else other than the pain.

Glenda held Linda’s hand and fed her ice chips. Linda told Glenda that having her had been as good as having four daughters. Glenda said she couldn’t have asked for a better mother.

As difficult as it was to watch her mother suffer, Glenda knew she was fortunate to remain by her side.

“It was a blessing, a bittersweet blessing, that we both got it and we were there together, and I was able to take care of her in a manner she was accustomed to, even in the hospital,” Glenda said later. “I made her days as pleasant and as happy as I possibly could. She was my heart, my life.”

Glenda’s vigil continued into the following day, April 13. That morning, Linda’s pulse was racing. The end seemed near.

Glenda gave her mother permission to die. “I told her I was going to be OK and if she saw my dad, to go with him. She said she hadn’t seen him because she did not want to die. She was fighting to live.”

Glenda asked if there was something the doctors could give her mother to ease her pain. The medication did not arrive in time.

Linda died holding Glenda’s hand.

Later, Glenda returned home alone. Her parents’ house was unkempt from the weeks of immobilizing illness and the hasty departure for the hospital. But she found some solace in being surrounded by elephant figurines, which Linda collected on her travels. Linda said they brought good luck. Glenda said the elephants symbolized Linda: majestic, loyal, protective.

Glenda believed her mother deserved a large and celebratory funeral that could accommodate all of her relatives and friends; 300 had attended her 80th birthday party. Instead, because of social distancing rules, the service would be limited to 10 people.

“I’m trying not to be bitter with God,” Glenda said recently from her parents’ house, where she fielded calls and deliveries of food and flowers. “But she did not die alone. So many people are dying alone.”

She turned on the television, but the news of the coronavirus’ toll overwhelmed her. More than 1,000 Detroit residents have died.

“I’m just so sick of coronavirus I don’t know what to do,” Glenda said. “It’s just too much. Every time I see the death total, I know my mother is in that number.”

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

On April 30, Glenda and a small group of friends and relatives, along with Linda’s pastor, all wearing face masks, attended an hourlong service at the Kemp Funeral Home in Southfield. Linda’s gleaming white casket was surrounded by bouquets of flowers.

Glenda did not speak. But she wrote a letter to her mother, which one of the mourners read aloud.

Glenda thanked Linda for making her feel loved and beautiful and for being her biggest fan.

“From time to time, you’d ask me if you were a good mother,” Glenda wrote. “I’d reply, ‘Momma, you’re the master at being a good mother.’”