The wrong battlefield —

Scientists “map” how distrust in health expertise spreads through social networks.

Jennifer Ouellette

–

Enlarge / Vials of measles vaccine at the Orange County Health Department on May 6, 2019 in Orlando, Florida.

Paul Hennessy/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Last year, the United States reported the greatest number of measles cases since 1992. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 1,282 individual cases of measles in 31 states in 2019, and the majority were among people who were not vaccinated against measles. It was yet another example of how the proliferation of anti-vaccine messaging has put public health at risk, and the COVID-19 pandemic is only intensifying the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories.

But there may be hope: researchers have developed a “map” of how distrust in health expertise spreads through social networks, according to a new paper published in the journal Nature. Such a map could help public health advocates better target their messaging efforts.

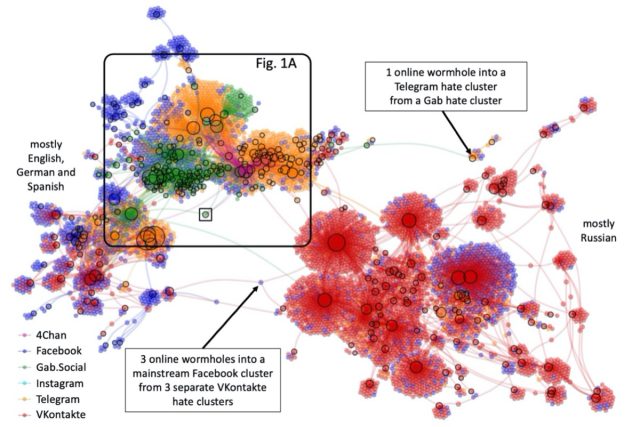

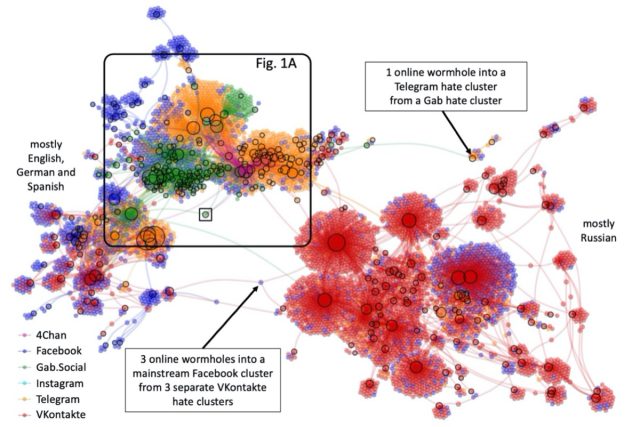

Neil Johnson is a physicist at George Washington University, where he heads the Complexity and Data Science initiative, specializing in combining “cross-disciplinary fundamental research with data science to attack complex real-world problems.” For instance, last year, the initiative published a study in Nature mapping how clusters of hate groups interconnect to spread narratives and attract new recruits. They found that the key to the resilience of online hate is that the networks spread across multiple social media platforms, countries, and languages.

“The analogy is no matter how much weed killer you place in a yard, the problem will come back, potentially more aggressively,” Johnson said at the time. “In the online world, all yards in the neighborhood are interconnected in a highly complex way—almost like wormholes. This is why individual social media platforms like Facebook need new analysis such as ours to figure out new approaches to push them ahead of the curve.”

A new world war

Johnson calls the rapidly eroding trust in health and science expertise a “new world war” being waged online, fueled in part by distrust of “Big Pharma” and governments, but also by the proliferation of misinformation about key topics in health and science (vaccines, climate change, GMOs, to name a few). That conflict has only intensified with the current COVID-19 pandemic. Following his war analogy, he decided to try to build a useful map of the online terrain to better understand how this distrust evolves. And he started with the topic of vaccines.

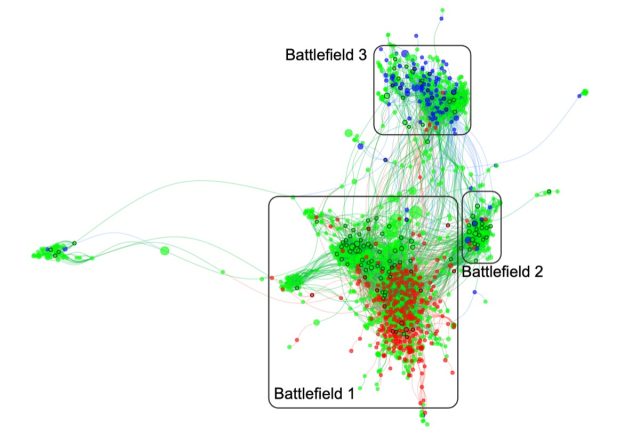

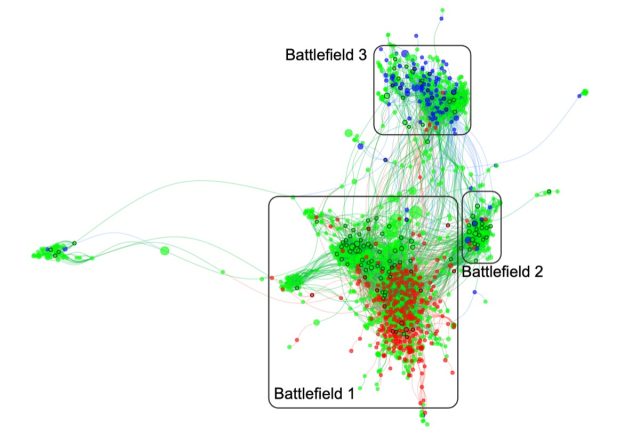

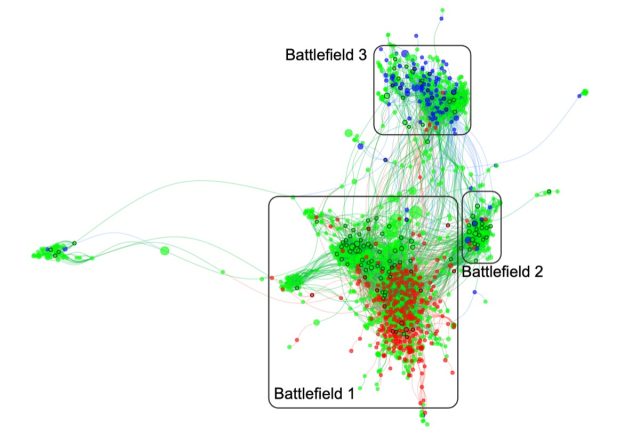

Johnson and his colleagues analyzed Facebook communities actively posting about the topic of vaccines during the 2019 measles outbreak—more than 100 million users in all—from around the world, mapping out the interconnected networks of information across cities, countries, continents, and languages. There were three main camps: communities that were pro-vaccine, communities that were anti-vaccine, and communities that were neutral or undecided regarding the topic (groups focused on parenting, for instance).

The researchers then tracked how the various communities interacted with each other to create a detailed map of the networks. “It’s not geographic, it’s to do with closeness in a social network sense—in terms of information, influence,” Johnson told Ars. “It’s not whether I’m here and someone’s in Australia. It’s the fact that someone in Australia agrees with my slightly twisted narrative on COVID-19 and I’m getting their feed. Although my neighbor doesn’t understand me, the person in Australia does.”

Enlarge / The first system-level picture of nearly 100 million individuals expressing vaccine views among Facebook’s 3 billion users across 37 countries, continents, and languages.

Neil Johnson

The results were surprisingly counter-intuitive. While there were fewer individual people who were anti-vaccine on Facebook, there were almost three times as many anti-vax communities clustered around Facebook groups and pages. So any pro-vaccine groups seeking to counter the anti-vaccine misinformation often targeted larger communities and missed the small- to medium-sized clusters growing rapidly just under their radar, according to Johnson.

While Johnson et al. expected their data to show major public health organization and state-run health departments in central positions in these networks, they found just the opposite: those communities were typically fighting the misinformation war in the wrong battlefield entirely. It’s akin to focusing on battling one big wildfire and missing the many different small brush fires threatening to spread out of control. In fact, “it’s even worse than that,” said Johnson. “It’s almost like all the fire departments are in the other valley. They’ve already put out the fires there, so they’re just sitting down relaxing.” In other words, the pro-vaccine groups aren’t reaching and interacting with the undecided groups nearly as effectively as the anti-vaccine communities.

From bad to worse

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the spread of misinformation has gotten even worse. “We didn’t stop the day we submitted this paper,” said Johnson. “We’ve been monitoring every day, every minute, the conversations and what you see in these Facebook pages, in these clusters, these communities. It’s gone into hyper drive since COVID-19.” He and his colleagues developed a predictive model for the spread, which showed anti-vaccine sentiment dominating public discourse on the topic within a decade. Furthermore, “that was a worst-case scenario if nothing was done as of December 2019, when we submitted the paper,” said Johnson. “Now it’s amplified. If we did that same study now, I think it would be a lot faster than ten years because of the COVID-19 situation. It’s the perfect storm.”

Johnson attributes this disconnect in part to the lack of diverse narratives being promoted by the most reliable scientific sources. “They’re into these large blue Facebook pages that are very straight with their message,” he said. “Vanilla is best. In other words, go and get a vaccine and do all the guidance that we tell you.”

“Each one of these Facebook pages has its own flavor of distrust.”

By contrast, the anti-vaccine narratives are tailored to mesh well with a broad variety of Facebook groups and pages. “Each one of these Facebook pages has its own flavor of distrust,” said Johnson. For example, one page will be devoted to distrust of Microsoft’s Bill Gates, while another will be focused on how world governments are supposedly behind a given outbreak, and still another could be a parenting group for those whose children show signs of autism, for example, and are convinced it’s because of vaccines. “It’s like going into an ice cream store and being asked, ‘Do you want vanilla? It’s the best vanilla there is. It will always tastes the same. It’s great,'” Johnson said. “Or do you want to try some of these other flavors?”

A good example of this type of insidious social spreading can be found in an article just published by Adrienne LaFrance in the June issue of The Atlantic, delving into the followers of the QAnon conspiracy theory. A 62-year-old New Hampshire woman named Shelly stumbled upon a QAnon video while browsing YouTube for something else—”she can’t remember for what, exactly, maybe a tutorial on how to get her car windows sparkling clean.” Now she’s a true believer. The ironic twist: she’s the mother of a political-science professor at the University of Miami named Joseph Uscinski who specializes in researching conspiracy theories.

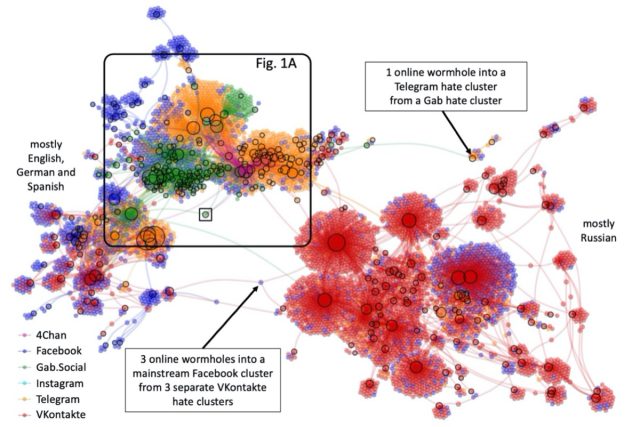

More bad news: COVID-19 misinformation is now being weaponized beyond these clusters to extreme online hate clusters (such as neo-Nazis) on other platforms, according to a draft paper Johnson et al. just posted to the physics arXiv. The paper treats each social media platform as its own universe within a larger online multiverse and analyzes how these universes interconnect over time via dynamical links (akin to wormholes) created by hyperlinks from clusters on one platform into clusters on another. They conclude, “Winning the war against such malicious matter will require an understanding of the entire online battlefield and new approaches that do not rely on future global collaboration being achieved between social media platforms.”

Enlarge / Online hate multiverse comprises separate social media platforms (i.e. universes) that interconnect over time via dynamical links (i.e. wormholes) created by hyperlinks from clusters on one platform into clusters on another.

N. Velasquaez et al./arXiv

A new study published in the journal BMJ Global Health bolsters Johnson et al.’s findings. Scientists at the University of Ottawa in Canada searched YouTube for the most widely viewed videos in English relating to COVID-19. They narrowed it down to 69 videos with more than 247 million views between them and then assessed the quality of the videos and the reliability of the information presented in each using a system developed specifically for public health emergencies.

The majority of the videos (72.5 percent) presented only factual information. The bad news is that 27.5 percent, or one in four, contained misleading or inaccurate information, such as believing pharmaceutical companies were sitting on a cure and refusing to sell it; incorrect public health recommendations; racist content; and outright conspiracy theories. Those videos—which mostly came from entertainment news, network, and Internet news sources—accounted for about a quarter of the total views (roughly 62 million views). The videos that scored the highest in terms of accuracy, quality, and usefulness for the public, by contrast, didn’t rack up nearly as many views.

The implications are clear: COVID-19 related misinformation is reaching more people than in past public health crises—such as the swine flu (H1N1) pandemic and outbreaks of Ebola and Zika viruses—because YouTube is becoming more of a source of health information for members of the public. “YouTube is a powerful, untapped educational tool that should be better mobilized by health professionals,” the authors suggested. “Many existing marketing strategies are static, in the form of published guidelines, statistical reports, and infographics, and may not be as appealing or accessible to the general public.”

A glimmer of hope

Johnson still believes that there is a glimmer of hope. His suggested strategy for combating misinformation is to use network mapping like the one just published for anti-vaccine sentiments to better target messages to specific groups—taking a page from the anti-vaxxer playbook, as it were. Because these are diverse communities, playing up the differences between them, rather than the common ground they’ve found in distrusting vaccines, might be one way to loosen the “strong entanglement” between them. “Just whatever you do, don’t have messages saying vanilla is best if it’s a strawberry group,” he said. “You need to know that these are different flavors out there.”

Exactly how this might be accomplished is beyond Johnson’s expertise, but it all starts with a map of the battlefield so that messaging efforts to combat misinformation find their way to the right targets. “If we knew the contact network for the real world, we wouldn’t have to have everybody shut indoors, because [social distancing efforts] could be precisely targeted,” he said. “Online, we can know the contact network. There’s a chance that we can actually deal with it better than we can deal with the actual virus. I think this has always been here. It’s just that now we’ve got a chance to actually see it online. You can’t deal with what you can’t see. So I am quite hopeful.”

DOI: Nature, 2020. 10.1038/s41586-020-2281-1 (About DOIs).

DOI: BMJ Global Health, 2020. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002604 (About DOIs).