From the land down under —

People may have used beeswax to shape the miniature stencils.

Kiona N. Smith

–

Brady et al. 2020

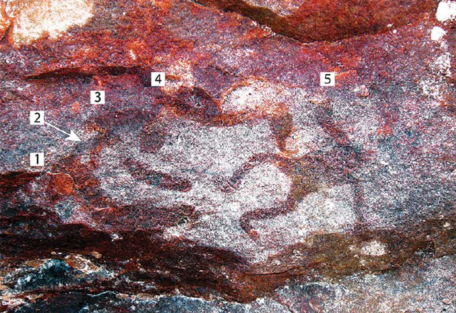

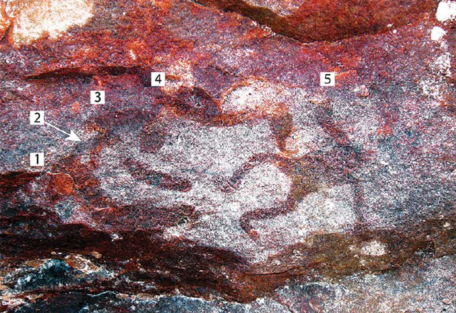

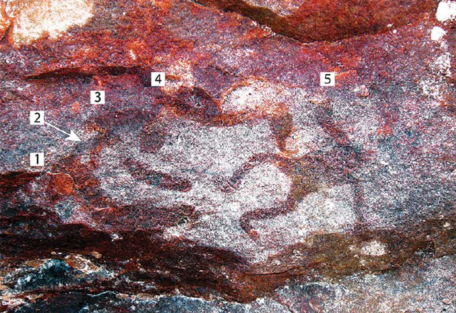

Ancient artists used several techniques to paint images on rock. Sometimes they drew by hand, but other times they would place an object like a hand, a leaf, or a boomerang against the wall and spatter it with paint, leaving behind a spray of color surrounding a silhouette of the object. This may sound like a simple way to produce art, but there’s new evidence that it could be a fairly complex process. People in northern Australia seem to have used beeswax to shape miniature stencils to paint on the walls of Yilbilinji Rock Shelter in Limmen National Park.

Welcome to Marra Country

The miniature images are part of a veritable gallery of rock art on the roof and rear walls of Yilbilinji. Over thousands of years, people came here to paint people, animals, objects, tracks, dots, and geometric motifs in striking red, yellow, black, and white. There’s even a European smoking pipe in the mix, which shows that at least some of the paintings must have been created after the colonists arrived.

Out of 355 images painted on the walls, only 59 are stencils—outlines of full-sized hands and forearms surrounded by sprays of white pigment (probably made with local kaolin clay). But 17 of those stencils are too small to have been done the usual way, by spattering an actual object with paint to leave a life-sized outline on the wall. They depict people—sometimes holding boomerangs and shields or wearing headdresses—crabs, echidna, at least two species of turtle, kangaroo pawprints, and geometric shapes.

And those miniature stenciled paintings are some of the only ones of their kind in the world, except for a tiny human figure stenciled on a cave wall in Indonesia and one in a rock shelter in New South Wales, Australia.

Of course, most of the drawings and paintings left behind by ancient people are smaller than life-size, but it’s much easier to draw a scaled-down version of an aurochs or a person than it is to stencil one. Unless you take the time to make yourself a model or template first, that is. And that seems to be exactly what the artists at Yilbilinji—which is traditionally the domain of the Marra people—did.

-

An exterior view of the rock shelter.

Brady et al. 2020 -

Over 350 rock art motifs adorn the walls and roof of Yilbilinji Rock Shelter.

Brady et al. 2020 -

Over 350 rock art motifs adorn the walls and roof of Yilbilinji Rock Shelter.

Brady et al. 2020 -

Starting at the top left, these stencilled images include a person holding a boomerang (6), a person holding a shield (7), a boomerang (8), a crab (9), and a long-neck turtle (10).

Brady et al. 2020 -

Brady and his colleagues used these beeswax figures to try to replicate the stencils at Yilbilinji,

Brady et al. 2020 -

Brady and his colleagues used these beeswax figures to try to replicate the stencils at Yilbilinji,

Brady et al. 2020

In which archaeologists mind their beeswax

Archaeologists and anthropologists, working with Marra rangers, noticed that most of the miniature stencils had rounded edges, and it looked like they had been sprayed over something that fit flush against the contours of the rock. That suggested the templates may have been something soft and easily molded, like clay, resin, or beeswax. And beeswax looks like the most likely option.

Today, the Marra and other people in northern Australia still use beeswax as an adhesive to repair spears, harpoons, and other tools; most men carry a ball of beeswax as part of their personal kit, just in case. But children also carry beeswax, which they mold into animals, people, and other objects—think of it as organic play-dough. Flinders University archaeologist Liam Brady and his colleagues wanted to find out if beeswax shapes could also be used to create stencils on rock, so they decided to play with some beeswax themselves.

When it was warm and soft, it only took a couple of minutes to mold the beeswax into a variety of shapes that looked like the stencils at Yilbilinji. Brady and his colleagues stuck their beeswax templates onto a slab of sandstone, then spattered it with paint from white kaolin clay and water. The results looked a lot like the Yilbilinji paintings.

That suggests beeswax could work—but is that really how the Yilbilinji artists made their miniature stencils? Brady and his colleagues didn’t get to date the paintings or test the rock shelter’s walls for microscopic traces of beeswax, resin, or some other soft, sticky material, but they hope to come back with the right equipment on a later trip.

What do these miniature motifs mean?

The stencils’ meaning is harder to figure out than how they were made. “No information about the potential meaning or significance was obtained from our Marra collaborators,” wrote Brady and his colleagues.

For the Marra, Yilbilinji Rock Shelter is a site associated with Karrimala, one of the Ancestral Beings who travelled through Australia during the Dreamtime to create the continent’s landforms, plants, animals, and people. Karrimala created the rock shelter and placed himself on the wall in the form of a painted snake. People lived at Yilbilinji in the past; the floor of the rock shelter is still littered with stone tools, grinding stones, and a stone-ringed fireplace.

At another rock shelter in Limmen National Park, Brady and his colleagues found small beeswax figures still stuck to the walls. The Marra men working with the archaeologists told them those figures were involved in a certain ritual, one they were nervous even talking about. Men whose families had the right connections to certain places, and who knew the right songs to sing, could use images on those places’ walls to magically attack their enemies, the Marra men told Brady and his colleagues.

But they also told the archaeologists that Yilbilinji Rock Shelter isn’t a site associated with that sort of thing.

“What is important here is that this discovery adds another dimension to the Australian and global rock art record,” said Flinders University archaeologist Amanda Kearney, a co-author of the study.

Antiquity, 2020 DOI: 10.1038/10.15184/aqy.2020.48 (About DOIs).