Threat level: brown —

Viral RNA levels spike in sewage seven days ahead of new cases.

Jonathan M. Gitlin

–

Aurich Lawson / Getty

Around the country and the world, coronavirus lockdowns and stay-at-home orders are being lifted as the rate of new infections begins to slow. That shouldn’t be interpreted as humans having suddenly beaten the virus; local outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 are going to be something we contend with until there’s an effective vaccine or widespread immunity. For public health officials, having as much notice as possible about those outbreaks will be vital. And it’s possible that sewage sludge might be able to provide that notice.

The idea is pretty simple. We know that infected humans shed SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in feces, so you can take samples of sewage sludge, look for the virus’s genetic materials, and thereby get an idea of the viral load of the pooping population.

In fact, the idea of using our sewers for biosurveillance isn’t a new one. I first heard the concept at the Advances in Genome Biology and Technology meeting in 2011, when biotechnology companies like PacBio and Oxford Nanopore proposed using their advanced new platforms to sequence the DNA in sewage for public health intelligence. But the idea was old hat even then—Israel has been monitoring sewage for signs of polio outbreaks since 1989, and it detected outbreaks in 1991, 2002, and 2013.

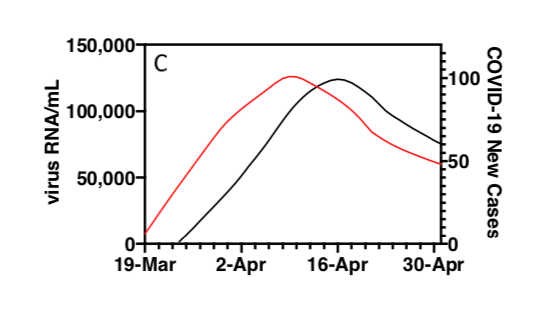

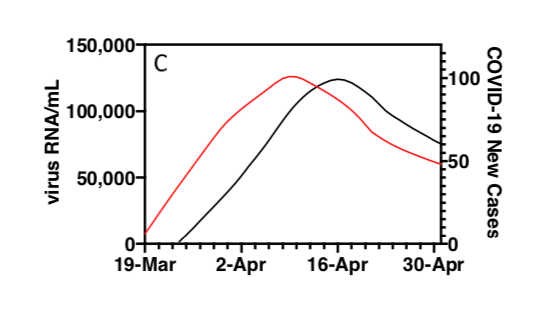

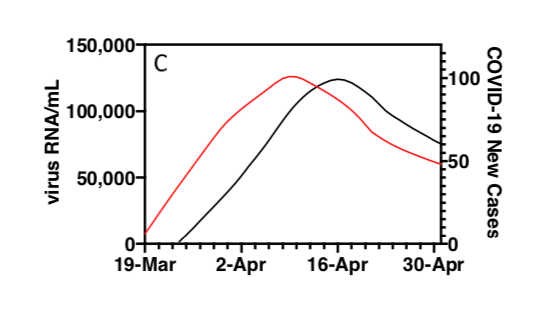

What makes the approach here all the more useful is the fact that changes in the amount of detectable virus in sewage sludge appears to mirror changes in the number of new cases—in fact, they give advanced warning. Those are the findings in a recent preprint from a group of researchers at Yale.

Between March 19 and May 1, the scientists took daily samples of sewage sludge from the East Shore Water Pollution Abatement Facility in New Haven, Connecticut, which serves a population of around 200,000 people. The researchers then measured the total amount of RNA in each sample, as well as the amount of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. This showed that levels of coronavirus rose over that time, peaked, and then decreased.

When the researchers then looked at daily COVID-19 admissions to the Yale New Haven Hospital, as well as laboratory confirmed cases in the communities served by the sewage plant, they discovered a clear correlation to the viral levels that lagged by seven days. In other words, a rise of viral load in sewage showed up a week before a similar rise in new COVID-19 cases.

A smoothed sludge SARS-CoV-2 virus RNA concentration (red) with smoothed COVID-19 epidemiology curve (black).

Jordan Peccia/Saad Omer/medRxiv

It should be obvious that a leading indicator of new cases like this could be much more helpful to public health officials than traditional lagging indicators like confirmed new cases; it’s the difference between shutting a stable door before the horse has bolted rather than afterward.

While this finding is still just a preprint, the results confirm those of researchers elsewhere in the country, as reported by The Washington Post at the beginning of May.

medRxiv, 2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.05.19.20105999 (About DOIs).