Image copyright

Getty Images

A woman wears a flu mask during the Spanish flu epidemic

It is dangerous to draw too many parallels between coronavirus and the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, that killed at least 50 million people around the world.

Covid-19 is an entirely new disease, which disproportionately affects older people. The deadly strain of influenza that swept the globe in 1918 tended to strike those aged between 20 and 30, with strong immune systems.

But the actions taken by governments and individuals to prevent the spread of infection have a familiar ring to them.

Public Health England studied the Spanish flu outbreak to draw up its initial contingency plan for coronavirus, the key lesson being that the second wave of the disease, in the autumn of 1918, proved to be far more deadly than the first.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Women from the Department of War take 15-minute walks to breathe in fresh air every morning and night to ward off the influenza virus during World War I, c. 1918. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The country was still at war when the virus claimed its first recorded victim, in May 1918. The UK government, like many others, was caught on the hop. It appears to have decided that the war effort took precedence over preventing flu deaths.

The disease spread like wildfire in crowded troop transports and munitions factories, and on buses and trains, according to a 1919 report by Sir Arthur Newsholme for the Royal Society of Medicine.

But a “memorandum for public use” he had written in July 1918, that advised people to stay at home if they were sick and to avoid large gatherings, was buried by the government.

Sir Arthur argued that many lives could have been saved if these rules had been followed, but he added: “There are national circumstances in which the major duty is to ‘carry on’, even when risk to health and life is involved.”

Image copyright

Getty Images

Women wear cloth surgical-style masks to protect against influenza

In 1918, there were no treatments for influenza and no antibiotics to treat complications such as pneumonia. Hospitals were quickly overwhelmed.

There was no centrally imposed lockdown to curb the spread of infection, although many theatres, dance halls, cinemas and churches were closed, in some cases for months.

Pubs, which were already subject to wartime restrictions on opening hours, mostly stayed open. The Football League and the FA Cup had been cancelled for the war, but there was no effort to cancel other matches or limit crowds, with men’s teams playing in regional competitions, and women’s football, which attracted large crowds, continuing throughout the pandemic.

Streets in some towns and cities were sprayed with disinfectant and some people wore anti-germ masks, as they went about their daily lives.

Image copyright

Getty Images

A telephone operator with protective gauze

Public health messages were confused – and, just like today, fake news and conspiracy theories abounded, although the general level of ignorance about healthy lifestyles did not help.

In some factories, no-smoking rules were relaxed, in the belief that cigarettes would help prevent infection.

During a Commons debate on the pandemic, Conservative MP Claude Lowther asked: “Is it a fact that a sure preventative against influenza is cocoa taken three times a day?”

Publicity campaigns and leaflets warned against spreading disease through coughs and sneezes.

In November 1918, the News of the World advised its readers to: “wash inside nose with soap and water each night and morning; force yourself to sneeze night and morning, then breathe deeply. Do not wear a muffler; take sharp walks regularly and walk home from work; eat plenty of porridge.”

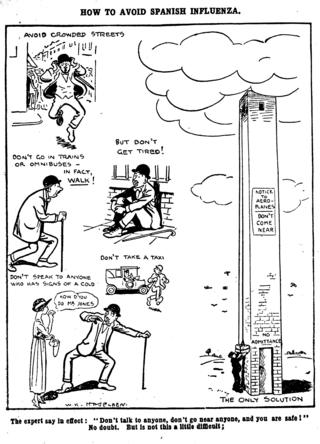

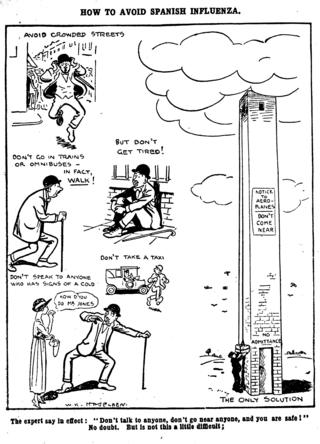

Image copyright

Mirrorpix

A Daily Mirror cartoonist captures the confusion over public health messages

No country was untouched by the 1918 pandemic, although the scale of its impact, and of government efforts to protect their populations, varied widely.

In the United States, some states imposed quarantines on their citizens, with mixed results, while others tried to make the wearing of face masks compulsory. Cinemas, theatres and other places of entertainment were closed across the country.

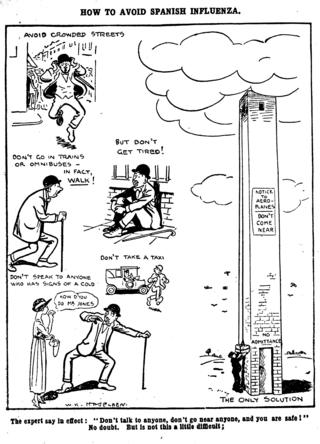

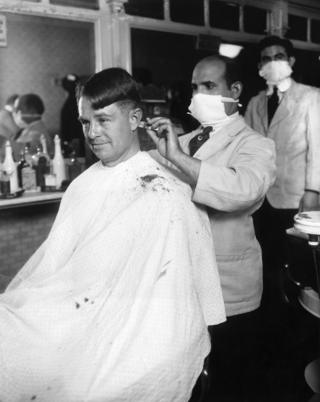

Image copyright

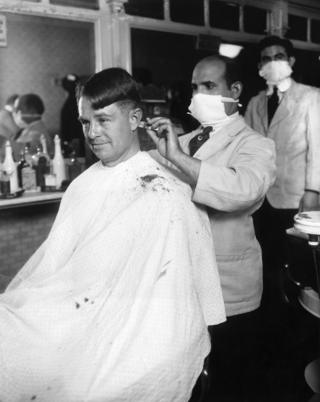

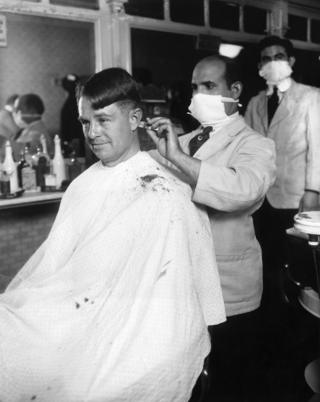

Getty Images

Hairdressers took precautions to curb infection

New York was better prepared than most US cities, having already been through a 20-year campaign against tuberculosis, and as a result suffered a lower death rate.

Nevertheless, the city’s health commissioner came under pressure from businesses to keep premises open, particularly movie theatres and other places of entertainment.

Image copyright

Getty Images

A New York city street sweeper wears a mask to help check the spread of the influenza epidemic, October 1918. In the view of one official of the New York Health Board, it is ‘Better be ridiculous, than dead’. (Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

Then, as now, fresh air was seen as a potential bulwark against the spread of infection, leading to some ingenious solutions to keep society going.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Court is held outdoors in a park due to the epidemic, San Francisco, 1918. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

But it proved impossible to prevent mass gatherings in many US cities, particularly at places of worship.

Image copyright

Getty Images

The congregation praying on the steps of the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption, where they gathered to hear mass and pray during the influenza epidemic, San Francisco, California.

By the end of the pandemic, the death toll in Britain was 228,000, and a quarter of the population are thought to have been infected.

Efforts to kill the virus continued for some time, and the population were more aware than ever of the potentially deadly nature of seasonal influenza.

Image copyright

Getty Images

A man sprays a bus of the London General Omnibus Co, with anti-flu preparation in March 1920. (Photo by H. F. Davis/Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

All photographs subject to copyright