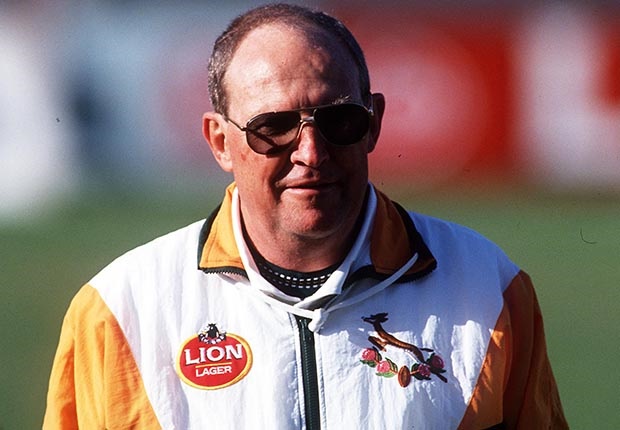

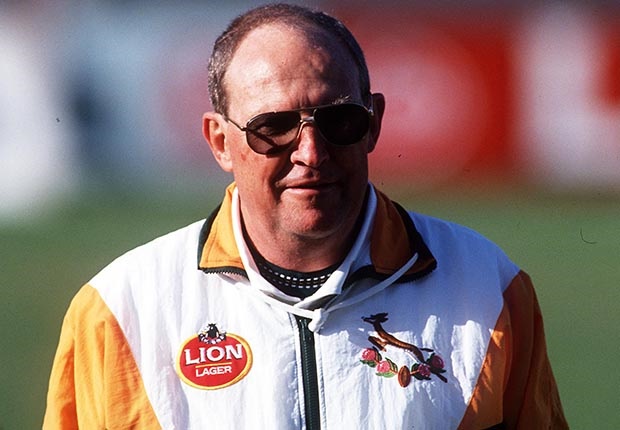

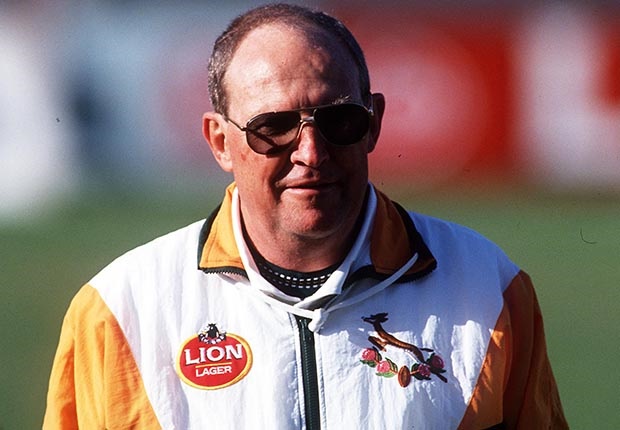

Kitch Christie (Gallo Images)

Heinz Schenk – Sport24

The Bulls have been in the news again these past few weeks following two high-profile administrative changes, prompting some cynics to believe all isn’t rosy at Loftus Versfeld.

CEO Alfons Meyer and director of rugby Alan Zondagh have both resigned in 2020, while Jake White’s appointment as the latter’s successor has been greeted with as much trepidation as excitement. However, president Willem Strauss insists the franchise’s board is arguably the strongest among South African teams, particularly after the acquisition of Patrice Motsepe as a shareholder.

In all honesty, the current hiccups pale in comparison to the drama of 1997, when Kitch Christie – the Springboks’ legendary World Cup-winning mentor – was controversially fired mere weeks into his tenure as Bulls coach … while he was in hospital!

When the game turned professional in 1995, a striking characteristic of that transition was how badly some of South Africa’s top unions grappled with it.

It was pronounced in Pretoria.

Under the guise of Northern Transvaal still in 1996, the team performed well in the inaugural edition of Super Rugby, reaching the semi-finals, and managed to claim their seemingly traditional spot in the last four of the Currie Cup.

But an undercurrent of discontent became increasingly stronger during the following year’s pre-season, when the re-branded Blue Bulls’ group of Springboks instigated a revolt against John Williams, who had been doubling up as head coach and CEO.

Before a ball was kicked, president Hentie Serfontein was forced to ratify the call for Williams to step down and gave in to the players’ demands that Christie replace him.

His appointment was a personal triumph.

To quantify just how significant it was, it’s useful to revisit Christie’s deep affiliation with the union.

Born in Johannesburg to a Scottish father and English mother and educated in Scotland, he joined local club giant Harlequins in the 1960s as a flanker before commencing his coaching career by marshalling the Under-20s.

Promotion followed expediently as Christie became a legend on the local circuit, winning numerous accolades as well a momentous national club championship title in 1983.

Sandwiched between those two tenures were two Murray Cup victories with Glenwood Old Boys in Durban.

The hierarchy at Northern Transvaal had taken notice, but the Afrikaans-centred culture of the union made it almost impossible for Christie to attain true fulfilment in Pretoria.

He became a provincial selector in 1985 and was assistant coach in three Currie Cup-winning campaigns between 1987 and 1990.

The suits though wouldn’t budge and Christie crossed the Jukskei river to transform the fortunes of Transvaal and the Springboks.

All this had been achieved against the backdrop of long-term battle with leukaemia.

On the crest of a wave after winning all 11 of his Tests in 1995, Christie decided to juggle his national post with Transvaal’s Super Rugby campaign.

It didn’t last long.

By March 1996, he had to sever all ties with rugby.

Typical of the man though, Christie fought so hard that by the end of that year that he felt primed again to make a return.

At the behest of the late Joost van der Westhuizen and co, Christie would finally fulfil a lifelong dream that seemed destined to elude him.

Naturally, doubts remained over the true state of his health.

The Bulls opened their Super Rugby campaign with a thrilling 40-all draw with eventual champions the Blues and a win over the much-fancied Reds.

Things went sour again from thereon.

Unable to make the trek for an early tour of Australasia, Christie’s condition worsened again to such extent that he had to be hospitalised.

It was clear that he’d struggle to fulfil his duties, but his dismissal defied belief.

Serfontein, weirdly given his reputation as a trusted mentor and legal advisor for various players, visited Christie and promptly fired him at his bed in the ward.

“He fired me like a dog,” was Christie’s pithy regaling of events.

To compound matters, Serfontein and his executive seemingly pushed back at the Bulls’ player power by astonishingly reinstating Williams.

Unsurprisingly, the mutiny was huge.

Naas Botha was asked to become the first spokesperson of the Northern Transvaal Players’ Union as the players organised themselves more diligently, allowing them to heap enough pressure for Williams to resign again.

However, the players’ list of reputable coaching candidates didn’t come to fruition simply because no-one wanted the job.

Forced to get things in order for 1998, the unassuming Eugene van Wyk bravely offered to put himself in the hot seat.

He was rewarded with a sentimental Currie Cup title that same year, but the Bulls’ financial position had deteriorated to such an extent that year that it required the now defunct SAIL to bail it out from bankruptcy.

Meanwhile, Christie was left to fend for himself and in October 1997 went to New York for a last-ditch attempt at specialised treatment.

The canny Falcons (now Valke and formerly Eastern Transvaal), who at that stage managed the transition to professionalism way better than Loftus, installed him as a technical advisor at the start of 1998, but he was back in hospital by Easter.

He died a few days later, aged 58.